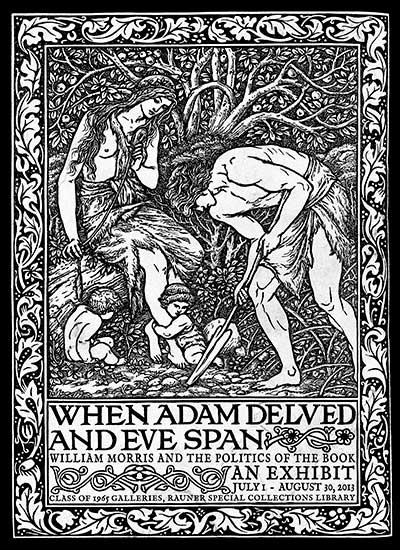

When Adam Delved & Eve Span: William Morris & the Politics of the Book

William Morris created a world of aesthetic rebellion. To him, the forces of modern industrial capital were destroying the products of noble labor and eroding the beauty of the human soul. Morris looked to an idealized past and imagined a socialist utopia devoted to the arts and crafts.

William Morris created a world of aesthetic rebellion. To him, the forces of modern industrial capital were destroying the products of noble labor and eroding the beauty of the human soul. Morris looked to an idealized past and imagined a socialist utopia devoted to the arts and crafts.

In his visions of this transformed world, Morris experimented in many areas of design. To most people, Morris is synonymous with late Victorian textiles, wallpapers, interior design -- even the Morris Chair -- but his ideals came most fully to fruition in the books he crafted. This exhibition looks at Morris’s socialist dreams as they played out in the realm of books -- those he wrote, those he loved, and those he printed.

The exhibition was curated by Laura Braunstein & Jay Satterfield and was on display in the Class of 1965 Galleries from July 1 - August 30, 2013.

You may download a small, 8x10 version of the poster: WilliamMorris.jpg. You may also download a PDF handlist of the items in this exhibition: WhenAdamDelved.

Materials Included in the Exhibition

Case 1. Co-operative Harmony

The rapid industrialization of Victorian England had many critics. William Morris was particularly offended by the triumph of commerce over aesthetics as a consequence of mass production. What was the alternative? For Morris, it was a return to what he saw as the primitive simplicity of the Middle Ages. His ideal of production, in which the individual talent is subsumed by collective creation, became manifest in his avocation as a printer, craftsman, and mentor to artisans. As he wrote in his lecture Gothic Architecture, the artist should aspire to “the freedom of hand and mind subordinated to the co-operative harmony which made the freedom possible.”

- William Morris. Gothic Architecture. Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1893. Presses K299mg

- Völsunga Saga: The Story of the Volsungs & Niblungs, with Certain Songs from the Elder Edda. Translated from the Icelandic by Eiríkr Magnússon and William Morris. London: F. S. Ellis, 1870. Val 838.5 V88 J21

- Morris argued in his preface that a modern reader should find a “startling realism, such subtlety, such close sympathy with all the passions that may move himself today.” For Morris, medieval literature represented an unmediated form of storytelling with emphasis on action and moral purpose.

- William Morris. A Dream of John Ball and A King’s Lesson. Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1892. Presses K299mdr

- Morris’s time-travel fantasy of a martyred hero of the 1381 Peasants’ Revolt imagined an edenic time before the existence of social class, with the rallying cry “when Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?”

- Ramon Llull. The Order of Chivalry. Translated from the French by William Caxton. Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1893. Presses K299ℓu

- Thomas Malory. The Story of the Moste Noble and Worthy Kynge Arthur. London, 1557. Rare Book PR2043 .W5 1557

- Morris’s book collection encompassed many medieval manuscripts and early printed books. He found in them inspiration not only for his philosophical ideals, but for book design as well. The Kelmscott edition of the thirteenth-century philosopher Ramon Llull’s treatise on chivalry echoes the layout of Morris’s copy of a 1557 edition of Sir Thomas Malory’s Arthurian tales.

- Thomas Aquinas. De arte praedicandi. Nuremberg: Friedrich Creussner, 1483. Incunabula 127

- Morris was inspired by medieval manuscripts and early German printing. His decorative flourishes attempt to capture the spirit of initial letters like this one in a 1483 edition of Aquinas.

- T. J. Cobden-Sanderson. The Ideal Book or Book Beautiful: A Tract on Calligraphy, Printing and Illustration & on the Book Beautiful as a Whole. Hammersmith: Doves Press, 1900. Presses D751cs

- The Doves Press, also operating in Hammersmith, looked back to early printing for inspiration as well, but found it instead in the humanist typography of the Italian Renaissance.

- Robert Burns. Tam O’Shanter. London: Essex House Press, 1902. Presses E78bu or Burns PR4314 .A1 1902

- When Kelmscott Press closed in 1897, Charles Ashbee founded the Essex House Press with many of the craftsmen who worked for Morris. Like Morris, he espoused a socialist ideal and put it into practice in his worker-owned shop. But also like Morris, the products he produced were far too expensive for the working class.

- William Morris. “Art in Socialism.” In Hand and Brain: A Symposium of Essays on Socialism. East Aurora: Roycrofters, 1898. Presses R813han

- One of the more flamboyant followers of Morris was Elbert Hubbard. He set up a colony devoted to the Arts and Crafts in East Aurora, New York. The press at the Roycrofters was used to promote Morris’s ideals, but on a scale and price to make them more accessible—and more profitable.

Case 2. Crafting Books

The Kelmscott Press was the most fruitful manifestation of Morris’s rejection of the modern industrial state. Morris hated the drab typography of late nineteenth-century commercial printing. Books, for Morris, had become shoddy commodities in a capitalist marketplace. Morris applied his romantic vision of the medieval craft guild to a small private press. Using the basic technologies developed by Gutenberg and his successors, he hired a team of artisans to set type of his own making, to execute woodcuts based on his designs and those of Edward Burne-Jones, and to print from a hand press on handmade paper. The results were stunning: Kelmscott Press issued some of the most beautifully printed books of the Victorian era. The Press’s output could never fulfill Morris’s socialist dreams—they were priced out of that class—but Kelmscott helped reintroduce typographic principles and fostered a movement that brought good design back to the mainstream.

- William Shakespeare. The Tragicall Historie of Hamlet Prince of Denmarke. Hammersmith: Doves Press, 1909. Hickmott 23 or Presses D751sh

- William Shakespeare. The Poems of William Shakespeare. Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1893. Hickmott 15 or Presses K299s

- These two editions of Shakespeare contrast the extravagance of Kelmscott Press and the restraint of the Doves Press. Philosophically in sync, but aesthetically opposed, they display the fine press movement’s medieval and humanist influences respectively.

- Willa Cather. Death Comes for the Archbishop. New York: Knopf, 1926. [1927 edition: Val 817C286 P6]

- Alfred Knopf was a champion of the typographic principles that emerged from Morris and his followers. He reasoned that it was wise to invest in good design and then spread the cost over thousands of copies of a trade book. His Borzoi Books set a new standard for commercial publishing and reached a mass audience.

- Punch. 15 December 1883. Sine Serials NC1478 .P873

- Morris’s hypocrisy was not lost on his critics. Punch satirized him for championing the shared means of production, but not actually sharing profits with his workers.

Case 3. Capitalizing on Socialism

Morris’s ideals of craft-based production failed to be realized when it came to their propagation. He nostalgically revived the medieval romance as the genre of the masses, but his works could only reach a broad audience through commercial publishing’s distribution networks. Many of the outrageously expensive fine press books produced by Kelmscott were also issued in cheap editions priced to sell, thus helping Morris to profit from the industrialized system that his writings and his life’s work aimed to critique.

- The Manifesto of the Socialist League. London: Socialist League Office, 1885. Rare HX11.S63 M26 1885

- Unlike lavish Kelmscott books, this pamphlet was cheaply produced and priced at one penny. Morris’s Socialist League had some success attracting membership—or at least attention—in the late 1880s, but disagreements with its anarchist elements led to its dissolution a few years before his death.

- William Morris. Letters on Socialism. London: privately printed, 1894. Rare HX246 .M68 1894

- A privately printed edition of Letters on Socialism (limited to 34 copies) framed the issue as a debate among select gentlemen, rather than a mass political movement.

- William Morris. Hopes and Fears for Art. London: Longmans, Green, 1886. Library Depository 700.4 M834h [not available at Rauner]

- William Morris. News from Nowhere; or, An Epoch of Rest, Being Some Chapters from a Utopian Romance. London: Longmans, Green, 1920. Baker Berry 826 M834 T6 [not available at Rauner]

- William Morris. The Life and Death of Jason, a Poem. London: Longmans, Green, 1914. Baker Berry 826 M834 S812 [not available at Rauner]

- Many of the cheap editions of Morris’s works were published by Longmans, Green. In Morris’s time, Longmans, Green published school textbooks, popular poetry, and mainstream social commentary such as the writings of Thomas Babington Macaulay and John Stuart Mill.

- Geoffrey Chaucer. The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, Now Newly Imprinted. Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1896. With original receipt, 1897. Presses K299c

- Rauner Library’s copy of the Kelmscott Chaucer was originally purchased by C. F. Richardson, Professor of English at Dartmouth College. The 1897 receipt shows that Richardson paid $160 for the text block, then an additional $104 for the deluxe binding produced at the Doves Bindery. Adjusted for inflation, that $264 is the equivalent of around $6,800 today.