More than a Monster:

Medusa Misunderstood

You might know her from Caravaggio’s famous Medusa, the face of Versace, the book, Percy Jackson and the Olympians, or some other adaptation of the ancient myth. Medusa is ubiquitous, appearing in Greek and Roman literature (from Hesiod’s Theogony to Ovid’s Metamorphoses) and in architecture, metalwork, vases, sculptures, and paintings throughout history. Yet the most well-known portrayals of her all predictably converge upon one brief moment from her life’s story: her beheading and the use of her decapitated head by a man to petrify others. Medusa then becomes an apotropaic symbol warding off evil, similar to the evil eye. She is imagined more often as an object or a monster than as a human. Even though Classical and Hellenistic depictions presented Medusa as more human than in the previous Archaic period, the popular conception of Medusa today still upholds her “otherness,” her monstrosity. Modern-day artists have embraced Medusa as an emblem of female power, a beautiful monster, and used her story in the service of social movements; for example, Luciano Garbati’s Medusa with the Head of Perseus went viral in 2020 in connection with the #MeToo movement.

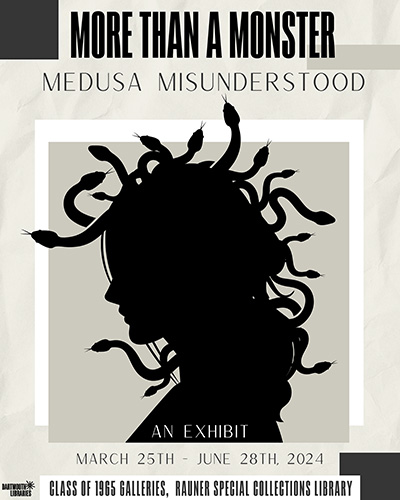

This exhibition, "More than a Monster: Medusa Misunderstood", serves to highlight the other half of her story, as it appears in Ovid–Medusa as a maiden, not a monster–her overlooked and overshadowed past. The exhibition was curated by Elizabeth Hadley '23, the Edward Connery Lathem '51 Special Collections Fellow, and will be on display from March 25th, 2024, through June 28, 2024. You may download a pdf of the exhibition handlist here. A printable version of the exhibition poster designed by Sam Milnes can be downloaded here.

Introduction

This following poem, from my thesis on Ovid’s Metamorphoses and the inspiration for the exhibition, explores Medusa’s perspective, looking back on her life when she was a maiden. In the Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Minerva punishes Medusa by turning her into a monster because Neptune raped her in Minerva’s temple. The title, “alternis inmixti crinibus angues” (“Snakes Mixed-In with Coiling Hair”), comes from line 792 of Book 4 of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Let this poem lead you into the exhibition, reframing Medusa as more than the monster you might know her to be.

alternis inmixti crinibus angues

People wouldn’t know this,

because nobody asks,

but I was once afraid of snakes.

I loved my beautiful auburn hair,

I enjoyed the male gaze.

I will never forget the day

when everything was taken from me.

My white dress stained red,

my hair no longer a comfort,

but my greatest fear.

What do you do when the one thing you’re afraid of is forced to become a part of you?

What do you do when you used to be chased after and now you’re fled from?

What do you do when you realize you’re no longer a woman, but a monster?

You learn to live with it.

That first month,

I didn’t sleep.

I couldn’t rest in fear they might slither around my neck and choke me in my sleep.

That first month,

I couldn’t look in the mirror.

I couldn’t see my sunken eyes,

I missed my locks.

That first month,

I thought I was going to go deaf from the hissing,

a sound so close to my ear,

fear also became a part of who I was.

Am.

CASE 1

MEDUSA AS YOU KNOW

Medusa’s more typical depictions feature her on a shield or as a decapitated head with snakes for hair. This first case highlights the Medusa you most likely know and learned in school or from a mythology book: Medusa as a monster, an object, a weapon. A head, a symbol, never a woman. Terrifying, never beautiful.

Reproduction of Giovanni Jacopo Caraglio, Pallas Athena, Plate 20 from the series Gods in Niches, Engraving on Wove Paper. Hood Museum of Art, Gift of Robert Dance, Class of 1977. PR.988.1.5.

In this engraving, the shield of Athena, the goddess of wisdom displays the face of Medusa. The deliberate comparison between Athena’s feminine aspect and Medusa’s monstrous appearance, with her wrinkles and her pupil-less eyes, suggests that Medusa is meant to scare: notice the viciousness in both Medusa’s and the snakes’ appearance. Also, according to myth, when someone looks at the head of Medusa, that person is turned to stone. Athena is deliberately adopting Medusa’s visage to use as a frightening talisman against the goddess’s enemies.

Ovid, Ovid’s Metamorphosis: Englished, Mythologiz’d, And Represented in Figures, Imprinted at Oxford, 1632. Hickmott 719.

This engraving portrays all of the myths in Ovid’s Book 5, including the scene where Perseus fights Phineus for his future wife, Andromeda, by petrifying him with Medusa’s head. This depiction of Medusa is one of the most popular. Medusa again is just an object, a weapon. Her face is weighed down with wrinkles, sagging into a frown, and snakes squirm from her head–there is no semblance of femininity in her sad gaze.

Laurent Cars, Perseus and Andromeda, Engraving on Paper. Hood Museum of Art, Gift of Susan E. Hardy, Nancy R. Wilsker, Sarah A. Stahl, and John S. Stahl in memory of their parents Barbara J. and David G. Stahl, Class of 1947. 2014.73.65.

Medusa appears first in Ovid’s Metamorphoses at the end of Book 4: the Greek hero, Perseus, saves the shackled Ethopian princess, Andromeda, from a sea monster by turning it into stone with Medusa’s head. In many later popular imaginings of this event, Perseus holds Medusa’s actual decapitated head to kill the monster. Here, however, Perseus uses Medusa’s visage on a shield, much like Athena’s, to save Andromeda from the sea monster. This interpretation dehumanizes Medusa even further by eliminating her actual severed head; it also conveniently distances Perseus, the protagonist, from his murderous act, instead highlighting his heroism.

Henry M. Brock, Perseus Rescues Andromeda, The Heroes or Greek Fairy Tales for My Children, Pen and Ink, and Watercolor, 1928. MS-1447, Box 14.

This proposed drawing/painting for a children’s mythology book includes another perspective of Perseus saving Andromeda from the sea monster, this time using Medusa’s actual head. However, whereas Perseus and Andromeda have a very lively peachy skin tone, Medusa has the same bluish-green coloring as the sea monster. In addition, the title of the scene is “Perseus Rescues Andromeda”: a clear example of how Medusa’s story has traditionally been employed to advance someone else’s narrative, thereby minimizing its importance and her autonomy.

Ovid, Les Metamorphoses d’Ovide en Latin et in Francois, Paris, 1767-1770. Illus O96mb Volume 2.

This book provides another instance of Perseus using the head of Medusa to help him. In this instance, he turns the King Atlas into stone with it after being refused a place to stay. Following the well-worn formula, Perseus holds out Medusa’s decapitated head, whose wrinkled scowl and screaming snakes only add to her monstrosity.

Galba, Roman Imperial, Sestertius, Bronze. Hood Museum of Art, Purchased through the John M. McDonald 1940 Fund. 2019.27.

This coin provides another example of how Medusa, with her ability to petrify others, became a symbol to ward off evil. The emperor Galba is wearing a baldric, or a sword belt, with Medusa’s face on it that was meant to intimidate enemies in battle much like Athena’s shield. The appearance of Medusa’s face on a baldric on a coin doubly objectifies her; this dehumanization stands in contrast to the present day, where Medusa medallions are worn as a symbol of female strength because of her power to petrify those who stand in her way.

CASE 2

THE TRANSITION OF MEDUSA

This case highlights the spectrum of Medusas, starting with the Greek version of the myth in which she is nothing more than a monster and moving towards a more human and feminine portrayal. These works of art highlight the nuance that is buried in Medusa’s myth, and the numerous ways in which artists have chosen to render Medusa.

Henry M. Brock, Perseus Pursued by the Gorgons, The Heroes or Greek Fairy Tales for My Children, Pen and Ink, and Watercolor, 1928. MS-1447, Box 14.

Medusa’s myth actually starts with a work by Hesiod, a Greek writer. In his version, Medusa is one of three Gorgon sisters, all with snakes for hair, claws, and scales–all monsters. Ovid took Hesiod’s myth and expanded it in his Metamorphoses, making all three Gorgon sisters beautiful maidens; only Medusa is turned into a monster. This drawing by Henry Brock stays true to Hesiod’s description of the three sisters as monstrous beasts. Even though she is one of three Gorgon sisters, she is mortal, while the other two are immortal. Medusa may be more beautiful than the other Gorgon sisters in myth, but there is always something different or terrifying about her.

Vincenzo Cartari, Imagines Deorum, Lugduni, 1581. Rare BL720.C25 1581.

In this book, all three Gorgon sisters are meant to be feminine monsters: they’re wearing dresses and don’t have any claws or scales. However, their beauty is diminished by their abnormal facial proportions, again reminding the audience that they are beasts.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, A Wonder Book for Girls & Boys, Boston, 1892. Illus C85h.

The Ancient Greek mythological view and the idea of Medusa strictly as a monster pervades the 19th century. This children’s book begins with a story about King Polydectes tasking Perseus to behead Medusa. This tale holds true to the Greek myth and presents Medusa as one of the three Gorgon sisters; the surviving two hide in fright after her beheading, despite being immortal themselves. The title of the story is “The Gorgon’s Head,” a deliberate choice that robs Medusa of her name.

Andre Racz, Perseus Beheading Medusa I, 1944, Soft-ground etching and engraving on medium weight cream wove paper. Hood Museum of Art, Purchased through a gift from the Cremer Foundation in memory of J. Theodor Cremer. PR.2004.35.

This abstract engraving shows Perseus’s beheading of Medusa. Perseus is the figure on the left, Medusa’s fallen body is towards the right, and Medusa’s decapitated head is in the upper right, with blood dripping from her neck. Just like so many other representations of Medusa, this engraving is meant to be terrifying. However, in this engraving, the artist abstracts the snakes on Medusa’s head so much so that they could be mistaken for hair. In addition, Medusa’s face seems even more human than Perseus’s–you can see her eyes, nose, and mouth, and you can almost feel her agony. This engraving as a whole is monstrous because of its subject, but Medusa is clearly human; her expression evokes sympathy and pity from the audience.

Ovid, Ovid’s Metamorphoses in Fifteen Books, London, 1717. Rare PA6522.M2 G3 1717.

In this scene from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Perseus kills Phineus with Medusa’s head. However, this representation of Medusa stands out from other more typical potrayals of her as a monster. Instead, this Medusa has smooth skin and looks innocent–even sad–and the artist has omitted all bloody evidence of her violent beheading.

Circle of Corrado Giaquinto, Perseus and Andromeda, Early-mid-18th Century, Oil on canvas mounted on board. Hood Museum of Art, Gift of Julia and Richard H. Rush, Class of 1937, Tuck 1938. P.979.141.

This painting of Andromeda, chained to the rock and waiting for Perseus to rescue her, emphasizes how feminine beauty was typically portrayed by Baroque artists: Andromeda has glowing, smooth skin, a calm face, and flowing hair. This rendition of Andromeda is remarkably similar to those of Medusa to its right and left. These Medusas have the same smooth, marble-esque skin of Andromeda, suggesting that Medusa can also be seen as not only human but as a paragon of feminine beauty.

Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, Medusa, about 1854, Marble. Hood Museum of Art, Purchased through a gift from Jane and W. David Dance, Class of 1940. S.996.24.

This sculpture demonstrates Medusa’s feminine power and defies misconceptions of her as a monster. Medusa as seen here is a strong woman–a queen, even–with snakes as her crown. Neither Medusa nor the snakes convey a sense of menace or danger. Instead, the snakes slither harmlessly around her, almost worshiping her. Here, Medusa is practically fully human: she is more than just an object or a weapon. She has more hair than snakes and isn’t just a bloody, disembodied head, but a bust, which is a format often reserved for living people, particularly important historical figures. She possesses the same soft, longing glance as Andromeda. If an observer didn’t know the story that inspired this sculpture, the viewer might not even recognize the subject as Medusa. View a 3D model of the bust via this link.

CASE 3

MEDUSA AND RAPE: MORE WOMAN THAN MONSTER

Most audiences today who are familiar with the traditional character of Medusa don’t know anything at all about her past or have misconceptions of the origins of her curse. In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the reason Medusa is metamorphosized into a Gorgon is because Neptune rapes her in Athena’s temple. Instead of blaming Neptune, Athena punishes the beautiful Medusa for the violation of her temple, and curses her by transforming her from a maiden into a monster. Although Ovid is the first author to truly humanize Medusa by telling this story, he only does so within the context of the myth of Perseus and Andromeda. In that tale, Ovid emphasizes Perseus as the heroic male protagonist who retells Medusa’s origin story after he’s used her severed head as a weapon to save the endangered Andromeda.

Only one book in all of Rauner’s many editions of Ovid’s Metamorphoses contains the actual scene of Neptune raping Medusa, a microcosm for the reception of her story in art and literature. Whereas acts of rape in many other Greek myths are well-known and central to an understanding of their narratives, Medusa’s is historically hidden and underrepresented. Instead, she is known for her beheading by heroic Perseus and for the people and monsters she petrifies both before and after her death. She is known for the terror she elicits and not her beauty or womanhood. As the books in this case demonstrate, even when Medusa’s rape is illustrated, it is minimized, especially when compared to other representations of rape from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, particularly at the level of body language.

Ovid, Ovid’s Metamorphosis: English, Mythologiz’d, and Represented in Figures, Imprinted at Oxford, 1632. Rare PA 6522.M2S3 1632.

The Rape of Persephone: This engraving from Ovid’s Book 5 of the Metamorphoses shows Medusa gruesomely again, but also contains the rape of Persephone. Hades, the god of the Underworld, sees the goddess Persephone in a field, abducts and rapes her and then forces her to be his wife. In this image, Persephone is turned away from Pluto, curved outwardly and reaching out in a clear attempt to escape from his grasp.

Ovid, Les Metamorphoses d’Ovide: mises en vers francois, Paris, 1698. Illus O96m Volume 1.

The Rape of Medusa: This is the only book that contains Medusa’s rape scene–particularly the moment when Athena catches her and Neptune in the temple. Whereas the women portrayed in the other books in this case have their arms reaching out to escape, Medusa raises her arms almost in guilt, as if she’s complicit in the act. In addition, she seems to be running away with–instead of away from–the perpetrator. Medusa is never pictured as fully a woman–here, she already has snakes coming out of her head. Moreover, the caption for this engraving doesn’t even mention Medusa’s rape–it focuses on the fact that her hair is changing into snakes, minimizing her tragic moment.

Placidus Lactantius, P. Ovidii Nasonis Matamorphoses, Antwerp, Belgium, 1591. Rare PA6531.L15 1591.

The Rape of Daphne: This book illustrates the famous story of Daphne and Apollo, where Daphne, trying to avoid being raped by Apollo, turns into a tree. Due to an arrow from Cupid, Apollo falls in love with Daphne, a beautiful nymph, and pursues her; wanting to stay true to her virginal oath, Daphne prays to her father, a river god, for help, who changes her into a tree to escape the rape. Here, even though she is rooted to the ground and immovable, Daphne’s tree form is clearly arching away from Apollo, her curving branches attempting to flee even as her trunk is firmly planted in the earth.

Ovid, La Metamorphose d’Ovide figuree, Lyon, 1564. Rare PA6523.M2 T6 1564.

The Rape of Orithyia: Boreas, the North Wind, falls in love with the Athenian princess, Orithyia, and, after a failed attempt to court her, decides to take her by force. This engraving depicts Boreas raping Orithyia. In her distress, Orithyia contorts her body in an unmistakable attempt to get away from her abductor. The wind blows her clothes in a similar curvature, emphasizing her desire to escape.

Agostino Musi, Apollo and Daphne, 1400-1600, Engraving on wove paper. Hood Museum of Art, Gift of Robert Dance, Class of 1977. PR.993.42.4.

The Rape of Daphne (Continued): This engraving similarly shows the curvature used in the other rape scenes. Daphne’s arms are raised, reaching away, and her face shows her agony in the moment. Even the roots–intrinsically immovable–possess the same posture.