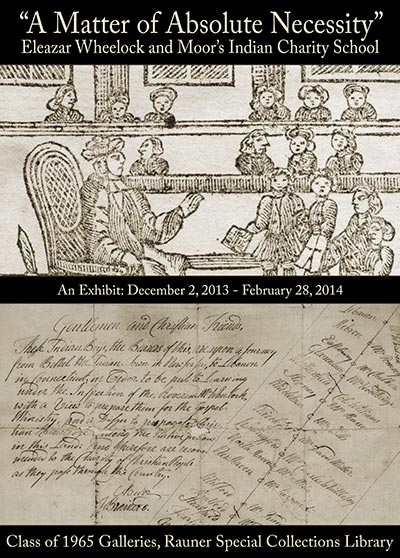

"A Matter of Absolute Necessity": Eleazar Wheelock & Moor's Indian Charity School

Of the many programs designed to educate Native Americans in the colonial period, Moor’s Indian Charity School, founded by Eleazar Wheelock in 1754, was the most ambitious. Moor’s was large, well organized and publicized. It was also founded on the premise that Indians would make better missionaries than their Anglo counterparts. This exhibit examines Wheelock’s educational philosophy, the daily life of Indian students at Moor’s Charity school, including the hardships students faced adapting to the English way of life, as well as the little-discussed experience of the women students at the school. The exhibit also explores the outcomes of Wheelock’s educational experiment, from successes like Samson Occom to the “failures” of those who returned to an indigenous life styles.

Of the many programs designed to educate Native Americans in the colonial period, Moor’s Indian Charity School, founded by Eleazar Wheelock in 1754, was the most ambitious. Moor’s was large, well organized and publicized. It was also founded on the premise that Indians would make better missionaries than their Anglo counterparts. This exhibit examines Wheelock’s educational philosophy, the daily life of Indian students at Moor’s Charity school, including the hardships students faced adapting to the English way of life, as well as the little-discussed experience of the women students at the school. The exhibit also explores the outcomes of Wheelock’s educational experiment, from successes like Samson Occom to the “failures” of those who returned to an indigenous life styles.

The exhibition, curated by Shermaine Waugh with assistance from Peter Carini and Barbara Kreiger, was be on display in the Class of 1965 Galleries from December 2, 2013 to February 28, 2014.

You may download a small, 8x10 version of the poster: MoorsCharity.jpg. You may also download a handlist of the items in this exhibition: MoorsCharity.

Materials Included in the Exhibition

Case 1. Moor’s Indian Charity School

Of the many programs designed to educate Native Americans in the colonial period, Moor’s Indian Charity School, founded by Eleazar Wheelock in 1754, was the most ambitious. Moor’s was well organized, large, and well-publicized. It was also founded on the premise Indians would make better missionaries than their Anglo counterparts in part because Indian missionaries could be supported for half the cost of English missionaries; they spoke the Indian languages; and they were accustomed to Indian lifestyles.

Moor’s grew out of Wheelock’s experience tutoring his first student, a Mohegan named Samson Occom, but Wheelock largely felt the plan was divinely inspired.. Located in Lebanon Connecticut the school was named for its chief benefactor, Joshua Moor, who donated a house and two acres of land. Like other schools of its kind the Indian boys who attended the Charity school were separated from their native culture. Unlike other schools they were given a classical education that included, in addition to bible studies the study of Latin and Greek. Indian girls also received schooling, but attended academic classes only one day a week. Their other training focused the household arts they would need to support the Christian brethren.

By 1768 about 50 students had studied at the school and 15 returned to their homes as missionaries, schoolmasters, or assistants to non-Indian Ministers. When Eleazar Wheelock realized that his plan of sending missionaries to Indian homelands to educate and convert Indians was not working as he desired, he began to move in a new directions. In 1769, he received a charter for a new school, which would be named for William, second Earl of Dartmouth. Wheelock would later be appointed Dartmouth College’s first president. Moor’s, relocated to Hanover New Hampshire, continued on as a sort of feeder school for Dartmouth, educating both Indian and English students who were not prepared to take on College level studies.

- In this 1756 letter to Reverend Whitefield, Eleazar Wheelock describes his disapproval over the state of neglect that has led to what he describes as “the piteous state of the Indian Natives of this Continent.”Wheelock believes the only solution to the “problem of the Indians” is to educate and spread the Gospel among them, which would hopefully keep them from a life of“hunting and rambling” (Mar. 1, Lebanon). MSS D.C. Hist. 756201 (MS-1310, Box 3)

- This small notebook consists of a list of students in attendance at Wheelock’s Charity School along with their dates of entrance (1757). MSS D.C. Hist. 757900.3

- The original Passport for Indian Youths on their journey from "Bethel," N.J. to Eleazar Wheelock's Charity School. The 'passport' combines, on a single sheet of paper, a letter and diagonally placed travel directions. The left side of the itinerary has twenty-seven place names, beginning with Bethel at the bottom of the page and Lebanon at the top. Each place name is complemented on the right side by a name of reference, where the boys could ask for assistance, food, and shelter (1754). MSS D.C. Hist. 754900 (MS-1310, Box 3). Manuscript donated by Rev. Henry Goodwin Smith.

- Towards the end of this letter from Wheelock to Sir Wm. Johnson Wheelock outlines his plan for Indian girls to be instructed “in all ye arts of good Housewivery, Tending a Da[i]ry, Spinning, the use of their Needle” as well as reading and writing (Dec. 11, 1761. Lebanon). MSS D.C. Hist. 761661 (MS-1310, Box 5)

- This letter from Eleazar Wheelock to Governor Wentworth explains the Charity School’s goals, and provides an account of its achievements. Wheelock stresses his goal to “cure the natives….of their savage temper, deliver them from their low, sordid and brutish manner,” and make them “good wholesome members of society, and obedient subjects to the king of Zion.” The letter also mentions of the importance of the Indian girls’ instruction in being good housewives (Sept. 21, 1762, Lebanon). MSS D.C. Hist. 762521.1 (MS-1310, Box 6)

- John Daniel, the father of one of the Indian boys attending Moor’s School Writes to Wheelock objecting to Wheelock’s focus on husbandry and having his son used for two years as a workhand on the farm while he is attending school. Daniel closes by withdraw his son from the school. (Nov. 30, 1767. Charlestown) MSS D.C. Hist 767630.3 (MS-1310, Box 17)

- A letter from John Smith detailing his visit to the Charity School and a day in the life of the Indian students, from the ringing of the schoolhouse bell to singing psalms and reading and reciting verses in English. (Boston, May 18th 1764) MSS D.C. Hist 764318.2 (MS-1310, Box 8)

- A writing sample from one of the students, Hezekiah Calvin, aged 11, a Delaware Indian. The sample is a copied Latin motto, and includes a note by Eleazar Wheelock about the writer on the back (Lebanon, Nov. 19, 1759.) MSS D.C. Hist 759619 (MS-1310, Box 4)

- Letter from Sarah Bingham to David McClure mentions the “ignorant” and “savage” behavior of the women at Wheelock’s Charity School along with disciplinary problems surrounding excess consumption of liquor. (August 1, 1787) MSS D.C. Hist. 787451 (MS-1311, Box 2)

Case 2. Hardships & Life after the Charity School

Although one of Eleazar Wheelock’s main goals was to use the Indian students to spread the gospel, the majority of the Indian students did not live up to these expectations and made no lasting evangelistic mark. In 1765, a total of eleven students graduated from the Charity school with three Indian boys becoming schoolmasters to the Iroquois and six serving as teaching assistants. Letters from students to Wheelock often depict the trials that the students faced and their recurrent struggles with alcohol, illnesses and adapting to the English way of life. Even Wheelock himself, at times found himself exhausted and frustrated not only with the troubles the students had acclimating and grasping the English language, but also with what seems like a perpetual lack of funding for the school. However, publically, Wheelock remained encouraged that his work would bring “something great” for the Indian students.

- In this letter from Joseph Fish reports to Wheelock on the condition and bad conduct of one of Wheelock’s former students, Jacob Woolley. Woolley has left the school and was found “at his Old Quarters” acting as a ne’er-do-well, collecting scraps of firewood. (Jan. 20 1764, Stonington) MSS D.C. Hist. 764120.2 (MS-1310, Box 8)

- Jacob Fowler writes with gratitude to Wheelock for his education and the opportunity to teach a school of Indians in Onawatagegh. (Jan.31 1767, Onawatagegh) MSS D.C. Hist. 767131 (MS-1310, Box 14)

- In this letter to George Whitefield, Wheelock details some of the problems encountered in educating the Indians. He is openly frustrated with their “savage” behavior and speaks of the troubles they have grasping the English language, getting used to furniture, and communicating. (July 4, 1761, Lebanon.) MSS D.C. Hist. 761404 (MS-1310, Box 5)

- The Connecticut Board of Correspondents report on the examination of Indian boys educated in the Charity School. The Board finds the boys “qualified for school matters.” MSS D.C. Hist. 765212.8 (MS-1310, Box 10)

- Eleazar Wheelock writes to Henry Sherburne about a lack of money for the school and notes that he feels worn out, but at the same time, encouraged that something great is near for “the pagans.” MSS D.C. Hist. 765220.2 (MS-1310, Box 10)

- Joseph Woolley, a former student, writes to Wheelock of bringing Christ to Indians at Onohoquawge. Woolley represents Wheelock’s goal of missionary service for the Indians post-Charity School. (Feb.9, 1765 Onohoquawge) MSS D.C. Hist. 765159.1 (MS-1310, Box 10)

- Draft of the charter for the Indian Charity School (1758). MSS D.C. Hist. 758900.3 (MS-1310, Box 4)

- Wheelock writes of the unsatisfactory nature of white missionaries for the school. He believed much more could be effected by training the Indians and returning them to their brethren. D.C. Hist. E97.6.M5.W5 1763 [Also available online via Hathi Trust]

- Portrait of Samson Occom by M. Chamberlin. Iconography 250

- The Boston Commissioners write to Eleazar Wheelock, revealing that they do not think the statements given out as to the training of Samson Occom, Wheelock’s first student, are true (Sep. 3, 1767. Boston). MSS D.C. Hist. 767503.3 (MS-1310, Box 16)

Case 3. Daily Life and Women’s Education

While the majority of the Indian students educated at Moor’s Charity school were male, Indian girls also received schooling. They attended academic classes one day a week, and the rest of their time was delegated to non-Indian households where they worked as servants. Students at Moor’s followed a strict schedule: Classes began at 9, ran until 12, and then again from 2 until 5. On Sundays, students attended church in the morning and the evening. The Indian boys began each day with prayer and catechism before dawn followed by formal instruction in Greek and Latin. The Indian boys were also required to work on the school’s farm for half a day, a task classified as “husbandry.” As illustrated in a letter from an Indian student’s (John Daniel) father, most of the Indian students and their parents showed little interest in farm chores.

- Confession of Mary Secutor, a female student at the Charity School. She admits that she has been guilty of drunkenness and disorderly conduct which “dishonurs God” in a tavern while in the company of other Indian boys and girls. MSS D.C. Hist. 768211.1 (MS-1310, Box 17)

- A sketch of the Moor’s Indian Charity School by a Siltig, G. Iconography 34

- A list of books that David Fowler carried into the Mohawk Country from the library to distribute among the boys that were attending school there. MSS D.C. Hist. 768900.2 (MS-1310, Box 19)

- Wheelock writes of the unsatisfactory nature of white missionaries for the school. He believed much more could be effected by training the Indians and returning them to their brethren. D.C. Hist. E97.6.M5.W5 1763

- In this letter, Samson Occom, Wheelock’s first Indian student addresses criticisms of his life and education by the Boston Commissioners. MSS D.C. Hist. 765628.1 (MS-1310, Box 12)

Case 4. Wheelock’s Philosophy of Education

Wheelock’s main goal for the Indian students at Moor’s was to solve the “problem of the Indians” and lead them from a “savage” life of “hunting and rambling” by making them into “good, wholesome members of society.” This, he posited, would solve the difference between colonists and the Indians and result in a more productive and peaceful existence for both. He felt that the way to accomplish this goal was through dutiful study of classical literature and Christian gospel.

Moor’s was set up for two different levels of schooling – a Latin school and an English school. At the English school, the students learned to read, write and do arithmetic. After completing English School, students began Latin School, where they learned to read and write Latin, Greek, and some Hebrew. The English School was reserved for Indian students while both white and Indian students attended the Latin School. Wheelock believed that by providing the Indians with this classical instruction, he would lay the foundation for a profession in ministry. The idea was to remove a child from the Indian environment as soon as possible and bring them up in English culture before Indian “savagery” had time to set in.

- A series of books likely to have been studied by the boys at the Charity School includes: Homer’s The Iliad, The Hebrew Old Testament, and The Orations of Cicero. Woodward 153 v.2, Woodward 322, Woodward 154

- A Hebrew primer annotated and illustrated by Samson Occom, Wheelock’s first student, and inspiration for the Charity School. The primer shows Occom’s familiarity and ability with languages at the very early stages of his education. Rare Book PJ4566.M71735 cop.3

- A Guide to the English Tongue and The British Instructor were two of books used in the English School for teaching the Indian students to read and write. Woodward 262, Woodward 257.