Dartmouth College Library Bulletin

Eleazar Wheelock's Two Schools

DICK HOEFNAGEL AND VIRGINIA L. CLOSE

It is commonly believed that the school established by Eleazar Wheelock in the early 1750s for the education of Indian youth, his Indian Charity School, was the forerunner of Dartmouth College. However, recent inquiry has provided clarification that an earlier school begun by Wheelock in the mid-1730s, his Latin School, was also important in the establishment of the College. Between 1754 and 1770, these two schools actually existed side by side, causing distinction between them to be difficult to apprehend, when the generic term 'school' was used in letters and documents. In order to help dispel the confusion that currently obtains, the schools will herein be discussed separately.

THE LATIN SCHOOL

Soon after his ordination in 1735 as pastor of the North Parish of the Congregational Church of Lebanon, Connecticut,[1] Eleazar Wheelock 'opened a school for the instruction of a small number. . . [of] English youth, preparing for admission into college.'[2] To be admitted to the school, a student had to be proficient in reading and writing, which usually had been taught by the minister of his home town. Wheelock, an accomplished student of the classics,[3] called it his 'Lattin School' for 'Lattin Scholars.' He preferred the employment of a double t,[4] and typically referred to his students as 'scholars.' Income from this school served to supplement his salary–necessary for the support of a growing family, consisting of his wife, three stepchildren, and three children born between 1735 and 1744. The Latin School students lived with the Wheelock family.

Records are lacking of the earliest days of the Latin School, except occasional correspondence from parents making inquiry regarding sons under Wheelock's care,[5] and an entry by Wheelock, in an account book, crediting a physician, Jonathan Huntington Sr., 'for doctoring for the School since 1737.'[6] Among the early students was Wheelock's stepson John Maltby (1727-1771), who was graduated from Yale College in 1747.

From existing sparse and incomplete records, names have been culled of sixty-six students who attended the school between 1743 and 1770. Of these, fifty-seven were 'independent'–that is, private students. The remaining nine were English students on charity. The majority of these boys came from towns in Connecticut close to Lebanon Crank, three from Massachusetts, and one from New York State. Most of the fathers were farmers, some were merchants or ministers. The boys varied in age from twelve to eighteen years. It took students from forty-five to forty-eight weeks to be ready for the final examination. The cost for 'schooling' was between one and one half and two shillings per week, with an additional charge for schoolroom, firewood, and books. School bills were usually paid in cash– as, for example, Ephraim Peas[e], a wealthy farmer, did in settling his account for a total of 48 and 1/2 weeks attendance by his sons at Wheelock's Latin School, which is recorded as follows:[7]

| 1760 | MrEphrm Peas of Enfield [CT] | �.s.d. |

| Octr 8 | his two Sons Peter an Obadiah | |

| came here to School- | ||

| May 9 [1761] | To 30 1/2 Weeks Schooling @2/ each | 6.2.0 |

| To firewood and School Room 20/ | 1.0.0 | |

| Oct.3 | To 18 Weeks Schooling at 2/ each | 3.12.0 |

| To School Room | 0.8.0 | |

| �11.2.0 |

After attending the Latin School, both Peter and Obadiah Pease matriculated at Yale College in 1761. Peter died in 1763, and Obadiah, at age 20, in 1766, the year following his graduation.

Thirteen other Latin School students were graduated from Yale College, and six from the College of New Jersey (Princeton). Some may have matriculated but withdrawn before graduation, a common occurence. Still others may have failed the examination required for admission to college.

Some fathers settled part of the bills in the form of 'country pay'–that is, by providing services, produce, or goods. For instance, Stephen Beckwith paid his bill of �5.8.6 with a saddle worth 4.10.0, plus 0.18.6 in cash. And Josiah Dunham's father paid with 2 bushels of rye, 1 1/2 of oats, a cow (�5.10.0), 40 pounds of flax, 17 1/2 pounds of honey, a barrel of vinegar, a 113-pound pig (at 2 pence a pound), firewood, and turnips. Gershom Breed included in his payment 'a teirce [cask] molasses 49 gallons' and bushels of salt. Daniel Whitmore paid with flax, while Thomas Davies made a barrel of cyder and 'pepper & alspice' part of his payment. Seth Wright paid most of the bill with '2 Saddles & Bridles & 1 horsewhip.' Colonel Shubael Conant gave 'a gun and ammunition' in partial payment of his son's expenses, and others paid with unspecified 'sundries.'[8]

The most renowned of Wheelock's Latin School graduates was a Mohegan Indian, Samson Occom, whose own account of what led him to put himself under Wheelock's care has been preserved in a

'Short Narrative of my Life,' which he wrote in 1768 to correct 'gross mistakes'[9] about his background that had previously been circulating in England and America:

-

From my Birth till I received the Christian Religion.-----

I Was Born [1723] a Heathen and Brought up In Heathenism, till I Was

between 16 & 17 Years of age, at a Place Call d Mohegan, in New

London, Connecticut, in New England. My Parents Lived a Wandering

life, as did all the Indians at Mohegan; they Chiefly Depended upon

Hunting, Fishing, & Fowling for their Living and had no Connections

With the English, excepting to Traffic With them, in their Small Trifles;

and they Strictly maintained and followed their Heathenish Ways, Customs,

& Religion, though there Was some Preaching among them. Once a Fortnight

in ye Summer Season, a Minister from New London used to Come up, and

the Indians, to attend; not that they regarded the Christian Religion, but

they had Blankets given to them every Fall of the Year and for these things,

they Would attend: And there Was a Sort of a School kept, Where I was quite

Young, but I believe there never Was one that ever Learnt to read any

thing. And When I Was about 10 Years of age there was a man who went

about among the Indian Wigwams, and Wherever he Could find the

Indian Children, Would make them read; but the Children Used to take Care

to keep out of his Way:–and he Used to Catch me Some times and make me

Say over my Letters; and I believe I Learnt Some of them. But this Was

Soon over too; and all this Time there Was not one amongst us, that made a Profession of Christianity–Neither did we Cultivate our Land, nor keep

any Sort of Creatures, except Dogs, Which We Used in Hunting; and we Dwelt in

Wigwams. These are a Sort of Tents, Covered With Matts, made of

Flags.[10] And to this Time we Were unacquainted with the English

Tongue in general, though there were a few, Who understood a little of

it.

From the Time of our Reformation till I left Mr Wheelock.-

When I was 16 Years of age, We heard a Strange Rumor among

the English, that there Were Extraordinary Ministers Preaching from

Place to Place and a Strange Concern among the White People: this Was

in the Spring of the Year. But We Saw nothing of these things, till Some

Time in the Summer, when Some Ministers began to Visit us and Preach

the Word of God; and the Common People also Came freequently, and exhorted

us to the things of God, which it pleased the Lord, as I humbly hope, to

Bless and accompany with Divine Influences to the Conviction and Saving

Conversion of a Number of us; Amongst Whom, I Was one that Was Impresst

With the things We had heard.[11] These Preachers did not only Come to us,

but we frequently went to their meetings and Churches. After I was

awakened & converted, I Went to all the meetings I could come at; & Continued

under Trouble of Mind about 6 Months; at which time I began to Learn the English Letters: got me a Primmer, and Used to go to my English Neighbors frequently for Assistance in Reading, but Went to no School. And When I Was 17 years of age, I had, as I trust, a Discovery of the Way of Salvation through Jesus Christ, and was enabl'd to put my trust in him alone for Life & Salvation. From this Time the Distress and Burden of my mind was removed, and I found Serenity and Pleasure of Soul, in Serving God. By this time I Just began to Read in the New Testament without Spelling,- and I had a

Stronger Desire Still to Learn to read the Word of God, and at the Same Time,

had an uncommon Pity and Compassion to my Poor Brethren According to the Flesh. I used to Wish, I was Capable of Instructing my poor Kindred. I used to think, if I Could once Learn to Read I Would Instruct the poor Children in Reading,–and Used frequently to talk With our Indians Concerning Religion. Thus I Continued, till I Was in my 19th year: by this Time I Coud Read a bit in the Bible. At this Time my Poor Mother was going to Lebanon, and having had Some Knowledge of Mr. Wheelock and hearing he had a Number of English youth under his Tuition, I had a great Inclination to go to him and to be With him a Week or a Fortnight, and Desired my Mother to Ask Mr. Wheelock, Whether he would take me a little While to Instruct me in Reading. Mother did so: and When She Came Back, She Said Mr. Wheelock Wanted to See me, as Soon as possible. So I went up, thinking I should Be back again in a few Days; When I got up there, he received me With kindness and Compassion and in Stead of Staying a Fortnight or 3 Weeks, I Spent 4 YearsWith him.[12]

So it was that twenty-year-old Samson Occom 'went to the Revd Mr. Wheelock of Lebanon Crank to Learn Something of the Latin tongue,' as the first entry in his diary reads.[13] Wheelock 'very willingly received young Occum into his [Latin] school, where he continued about three years . . . pursuing the study of the English, Latin and Greek languages, during which time he also attained some acquaintance with the Hebrew. It was at first designed that he should complete his education at college, but want of health, first affecting his eyes, compelled him to desist for a season, and finally to relinquish the plan.'[14] Occom lived in the Wheelock household, except 'when my Family [that is, the Wheelocks] were unable to bear the Burden of the School, by Reason of Sickness . . . the better part of a year.'[15] This was the year of the final illness of Wheelock's first wife, Sarah, who died on 13 November 1746. The school, during that time, was kept at nearby Hebron, in the home of Wheelock's brother-in-law Benjamin Pomeroy, who was assisted by Alexander Phelps, then a recent (1746) graduate of Yale College and a future son-in-law of Wheelock.

Little is known of Occom's life at Lebanon Crank. (He joined the church, and accompanied Wheelock in September 1744 to the commencement exercises at Yale College.) However, there have recently come to light some details of Occom's years at the Latin School, dealing with expenses relating to his personal needs between 1 January 1746 and 14 October 1747 and a summary of the income involved in defraying the overall cost of his education. Both accounts were written by Wheelock. First, the expenses:[16]

| Samson Occom | D[ebto]r �.s.d | |

| Jany 1 | To a pair of Shoes | 1.4.00 |

| AD 1745.6[17] | for making a Cape Coat | 00.19 |

| For a coat and the making | 2.2.00 | |

| March 20. | Paid to Dr Perkins[18] for Samson 5/ | 00.5.00 |

| To Mrs Bills Nursing when sick 10/ | 00.10.00 | |

| To Dryden's English Virgil 60/ | 3.00.00 | |

| Novr 1746 | To 3 yds of Half Thick [coarse woollen | |

| cloth]. 1 doz: Buttons | ||

| One stick of Mohair [a roll of material made | ||

| from Angora goat hair] | 4.00.00 | |

| Work Done in Making and Mending | ||

| Cloaths by Mrs Bill upon her Book | 2.00.6 | |

| Novr | To a Deer's Skin for Breeches (Paid to Clark | 4.5.00 |

| 42/ for ye Skin | ||

| To Nursing when he was sick | 1.00.00 | |

| To Sole Leather and Making two pr of Shoes | 1.18.00 | |

| To a pr of Stockins 20/ | 1.00.00 | |

| Jany 1. 1746/47 | To a Virgil, Tully [Cicero] & English Exercise | 5.16.8 |

| (Samson sent 4=16=0) | ||

| Jany 7.1746[/47] | To Flannel for two Shirts | 3.11.6 |

| By Ephm Loomis for mendg his shoes | 00.3.00 | |

| March 31 | To 5 1/4 yards of Plain Cloath for a Coat | 9.3.9 |

| of Jona Clark @ 35 pr yd | ||

| To making a Flannel Shirt | 00.8.00 | |

| To footing a pair of Stockings | 00.5.00 | |

| To two yards & a half of tough Cloath | 1.5.00 | |

| To Sole Leather for a pair of Shoes and making | 1.2.0 | |

| To making his coat | 2.4.0 | |

| By Mr Eliot Accot | 0.18.0 | |

| for Board and Schooling | 109.0.0[?] | |

| Ye whole acco . . . to this 14 day of | ||

| Octr 1747 | 156.3.5 | |

| Balance now due | 30.9.11 | |

| Samson went away in Novr |

According to Wheelock: 'Mr Occom had long been confined by sore [serious] sickness before he came to me & all the time he was with me in a low state of health, though in the main mending.[19]

Occom himself wrote: 'While I Was at Mr. Wheelock's, I Was very Weakly and my Health much Impaired, and the End of 4 Years, I over Strained my Eyes to such a Degree, I Could not pursue my Studies any Longer; and out of these 4 Years, I Lost Just about one Year: –And was obliged to quit my Studies.'[20] Some episodes of his illness must have been serious enough to require a visit or visits of Doctor Perkins [not further identified], and nursing care by Mrs. Joshua Bill, who also did work as a seamstress. At that time her husband, a farmer, frequently sold pork to Wheelock. The expeditures for Occom’s clothing, shoes, and books appear to have been more than generous.

As Occom could not have been an independent, 'upon pay' student of the Latin School, how then was he supported in the expenses of his education?[21] Wheelock only referred to ‘the Assistance of the Honourable Commissioners in the Education of Mr. Samson Occom.' More detail was supplied by Occom himself:

After I had been With him Some Time, he began to acquaint his Friends of my being With him, and of his Intentions of Educating me, and my Circumstances. And the good People began to give Some Assistance to Mr. Wheelock, and Gave me Some old and Some New Clothes. Then he represented the Case to the Honorable Commissioners at Boston, Who Were Commission'd by the Honourable Society in London for Propagating the Gospel among the Indians in New England and parts adjacent, and they allowed him 60 � in old Tenor,[22]which was about 6 � Sterling, and they Continu'd it 2 or 3: Years I Can't tell exactly.–[23]

In the second half of the account–that pertaining to income–are summarized contributions made by the Boston Commissioners of the Society in London and by a number of Wheelock's colleagues. The account indicates that until the expenses for Occom's education had come within the purview of the commission Wheelock himself had expended �84.14.0 in the cause, for which he was fully reimbursed. This was followed by further payments, the penultimate one, bearing the date of 11 November 1747, being the day Occom left the Wheelock family.[24]

| Jany 27 | The Honle Comissrs . . . For Samson Occom | �.s.d. |

| 1745/6 | To Cash=84=14=0 My accot before he | |

| was recommended to ye Comissre . . . | 84.14.00 | |

| May 21 | Samson has been absent in ye whole | |

| since last August four Weeks & 3 Days | ||

| August 18. 1746 | Recd Cash. �18=13=6 | 18.13.6 |

| Jany 1 1746/7 | Recd Cash30=00=0 | 30.00.0 |

| June 15 1747 | Recieved Cash �30.00 0 | |

| Octr 14 1747 | Recd of ye Comissrs | 100.13.6 |

| assn ye Reckd Due now from | ||

| ye Commrs to ye 14 of Octr | 25 .0.0 | |

| Mr Avery | 2.0.0 | |

| Mr Moseley | 2.0.0 | |

| Mr Devotion | 2.0.0 | |

| Mr Saltar | 2.0.0 | |

| Mr Eliot | 2.0.0 | |

| Mr White | 2.0.0 | |

| Mr Cogswell | 2.0.0 | |

| Mr Williams of Lebanon | 2.0.0 | |

| Novr 11 1747 | of ye Hon le Comissrs & Mr Pomfrett | 34.0.0 |

| 50.0.0 | ||

| June 22 1748 | Rec'd of ye Comissrs �15/ |

Important for future reference is that these ledger entries establish that Occom was in fact a charity student at the Latin School, perhaps the first and only Indian to be enrolled therein. His eventful life after leaving the Latin School has been frequently told, most comprehensively by De Loss Love, by Harold Blodgett, and by Leon Burr Richardson.[25]

Without the Latin School, it is unlikely that Samson Occom would have become Wheelock's student, and, as a consequence, the second school, the Indian Charity School, might not have been established. This, in turn, might have precluded the founding of Dartmouth College, indeed.

But the question arises: What could account for the lack of prominence given to Wheelock's Latin School in the annals of Dartmouth College? Could it be associated with the fact that the school, as a private enterprise, was not in need of a charter of incorporation? Had Wheelock sought a charter, the quest for it would probably have engendered much prominence for the name–as was surely the case in his failed pursuit of a charter for his Indian Charity School and his successful pursuit of one for Dartmouth College.

GENESIS OF THE INDIAN CHARITY SCHOOL

In few of Eleazar Wheelock’s writings is there a more personal tone than in those dealing with the plight of the Indians of North America. For instance, Wheelock wrote in a letter 'To the Sachems and Chiefs of the Mohawk, Oneida, Tuscarora, and other nations and tribes of Indians':

I have had you upon my heart ever since I was a boy. I have pitied you on account of your worldly poverty; but much more on account of the perishing case your precious souls are in, without the knowledge of the only true God and Saviour of sinners. I have prayed for you daily for more than thirty years, that a way might be opened, to send the gospel among you, and you be made willing to receive it. And I hope God is now answering the prayers that have long been made for you, and that the time of his mercy to your perishing nation is near at hand.[26]

He repeatedly referred to past neglect of them, which had led to such a 'piteous State of the Indian Natives of this Continent, who have been perishing in vast Numbers from Age to Age for lack of Vision.'[27] Although he felt much blame rested with 'mischievous, unrighteous, oppressive English and Dutch Traders,'[28] it was lack of 'publick Guilt on account of past Neglect'[29] that concerned him deeply.

And taking it even more personally, he did not think 'of any Thing more than only to clear myself, and Family, of partaking in the public Guilt of our Land and Nation in such a Neglect of them.'[30]

As for the Indians themselves, Wheelock repeatedly noted a 'lack of vision,'[31] implying that, without foresight in planning for their future, they were destined to continue their peripatetic life of 'Hunting & Rambling.'[32] An absoute prerequisite to a settled and stable existence was agriculture: '[T]heir present Roving Manner of Living . . . they can’t avoid till Agriculture be introduced among them.'[33]

There was, of course, in Wheelock's view, only one general solution to the predicament, a spreading of the Gospel among the Indians. As he was aware of the numerous pitfalls and failures of earlier attempts by others, Wheelock proposed an approach (probably not fully original) that he described in letters and in memorials (solicitations for funds):

. . . tho' my Straitn'd circumstances in the World forbad My doing much for them, Yet I could not but be plotting for them, and devising Some Methods, to Spread the Knowledge of the true God, & only Saviour among Them. And when I have considered the Difficulties attending an English Mission among them, arising from . . . the deep-conceived Prejudices against the English, arising partly from the unrighteous Dealings of Many bad men with them . . . but principally from the Subtle Insinuations of great Numbers of Jesuits, industriously employ'd for that Purpose. And also the almost insuperable Difficulties in learning their Languages, And the Difficulty, if not Impossibility of getting Interpreters, who are capable, & faithfull to communicate Spiritual things in their True Light. And many more, and great Impediments, in the Way of an English Mission among them, which can Scarcely be represented, and Set in a Light Strong enough, to one who is not personally acquainted with the Affair, or intimately acquainted with those who are in it. I say when I have considered these things, it has been Settled in my Mind, the Most likely Expedient, for accomplishing the great Design, is to take of their own Children, (two or more of a Tribe, that they may not Loose their own Language) and give them an Education Among ourselves, under the Tuition, & Guidance of a godly, & Skillful Master; where they may, not only, have means to Make them Schollars, but the best Means to Make them Christians indeed . . . to fit them for the Gospel Ministry among their respective Tribes. It seems to me, the Acquaintance they will get in Such a School, with one another's Person, and Languages (for it is not in general hard for them to learn one-another's Language) and the Friendship they will contract who belong to Tribes. 2. 5. 10. 20. hundred Miles distant, will probably greatly Subserve the great Design. And besides this it will be a most likely Expedient to remove their Prejudices, attach them to the English & to the Crown of Great Brittain.[34]

Wheelock stressed the benefit of his experience in the education of Samson Occom: 'And I was not a little Encouraged in this Affair by the Success of the endeavors I us'd . . . in ye Education of Samson Occom who has been usefull . . . beyond what could have been Reasonably expected of an English man & with less than half of the Expence.'[35] (Occom was, of course, twenty years old when he voluntarily joined Wheelock's Latin School, in contrast to the plan to take young children from their homes into what could be called a boarding school.)

Wheelock also considered the beneficial influence his design could have in preventing the horrors of recurring Indian wars:

AND there is good Reason to think, that if one half which has been, for so many Years past expended in building Forts, manning and supporting them, had been prudently laid out in supporting faithful Missionaries, and School-Masters among them the instructed and civilized Party would have been a far better Defence than all our expensive Fortresses, and prevented the laying waste so many Towns and Villages: Witness the Consequence of sending Mr. Sergeant to Stockbridge, which was in the very Road by which they most usually came upon our People, and by which there has never been one Attack made upon us since his going there . . .[36]

Wheelock declared: 'WITH these Views of the Case . . . I wrote [May 1754] to the Reverend John Brainerd, Missionary in New-Jersey, desiring him to send me two likely Boys for this Purpose, of the Deleware Tribe: He accordingly sent me John Pumshire, in the 14th, and Jacob Woolley in the 11th Years of their Age; they arrived here [Lebanon, Connecticut] December 18th. 1754.'[37]

Of the two boys, John Brainerd had written on 27 November:

The biggest boy [Pumshire] has been with me; and I must needs say I have been somewhat disappointed in him, both as to his natural abilities and the temper of his mind. Neither his judgment nor memory is as good as I thought, before I had a particular acquaintance; and yet I cannot but hope he may do pretty well in that respect. The temper of mind he has shown also has given me much uneasiness, especially of late: I find he has never had any government [discipline]. I have taken much pains with him, and thought several times that I must have given him up. Correction, it is highly probable he will stand in absoute need of: he must by no means be humored and made much of. He is proud, very high-spirited, and has too great a conceit of himself, which must be mitigated and mortified. . . . The little one [Jacob Woolley)], I think, is a boy of a good natural temper: he seems to discover something of it in his countenance. But I believe he also has had his head very much; for he had had nobody to take care of him but an aged grandmother of near fourscore, and will doubtless stand in need of some discipline.[38]

At the time of the boys' travel, 'New Jersey and adjacent portions of Pennsylvania, Delaware and New York were occupied by the Lenape ("Original People"), or Delaware, as they later came to be known by the whites.'[39] David Brainerd (1718-1747), a Presbyterian missionary, had served a number of Delaware Indians in a mission first settled in East Jersey at Crosweeksung [Crosswicks], and subsequently moved to a location about two miles northeast of Cranberry (Cranbury) called Bethel (Hebrew 'House of God'), a name to disappear with the disbandment of the mission. Bethel was often referred to as 'the Indian town.' Ill health had forced David Brainerd to suspend his missionary labors in early 1747, to be succeeded by his brother John (1720-1781).[40]

When exactly the boys left the mission at Bethel is not clear, but it was probably on or slightly before 27 November 1754, according to a letter of that date of John Brainerd: 'I have sent the Indian boys mentioned in my last, not without some reluctance, and a great deal of concern.'[41] He had commented that 'The children in general [in the mission at Bethel] seem to be as apt to learn as English children, and some are very forward considering the opportunity they have had . . . [and] are able to read pretty distinctly in the Bible.'[42]

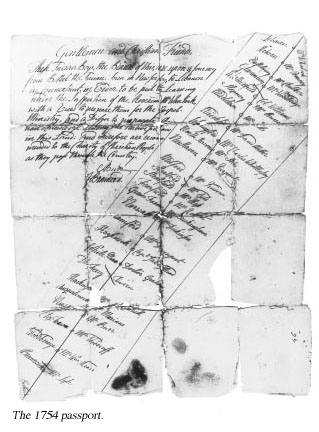

An interesting document came to light in 1933, when the Reverend Mr. Henry Goodwin Smith (1860-1940) of Troy, New York, a great-great-grandson of Eleazar Wheelock, presented to the College 'the original Passport for Indian Youths on their journey from "Bethel," N.J. to Rev. Eleazer Wheelock's school at Lebanon, Conn.' An accompanying letter notes that

This Document was lately discovered among the effects of William Allen, D.D. . . . whose wife, Maria Malleville Wheelock, was daughter of President John Wheelock, and so a granddaughter of President Eleazar Wheelock. It is a sheet 15 inches long and 12 inches wide, folded into fourths each way, much worn and with the pieces stitched together at the folds. [43]

A large collection of letters and documents preserved by Eleazar Wheelock had come down through his son John, whose only child, Maria, married William Allen (1784-1868), who served as president of Dartmouth University during the upheaval of the Dartmouth College Case (1815-1820) and subsequently became president of Bowdoin College.

The 'passport' combines, on a single sheet of paper, a letter and diagonally placed travel directions. The configuration of the former indicates that it was written after the completion of the latter:

Gentlemen And Christian Friends,

These Indian Boys, the Bearers of this, are upon a Journey fromBethel the Indian Town in New Jersey, to Lebanon in Connecticut,

in Order to be put to Learning under the Inspection of the Reverend

Mr Wheelock, with a View to prepare them for the Gospel Ministry,

and a Design to propagate Christian Knowledge among the Native

Indians in this Land: and therefore are recommended to the Charity of

Christian People as they pass through the Country.

[signed] A. Burr

J. Brainerd.[44]

Aaron Burr Sr. (1716-1757) had been president of the College of New Jersey since 1748; he was a son-in-law of Jonathan Edwards and father of the notorious Aaron Burr Jr. The college moved from Newark to Princeton upon completion of the building of Nassau Hall in 1756. President Burr died in September 1757; he was a close friend of Wheelock.[45]

The left side of the itinerary has twenty-seven place names, beginning with Bethel at the bottom of the page and Lebanon at the top; each place name is complemented on the right side by a name of reference, where the boys could ask for assistance, food, and shelter. A squiggle across the midline of the map–after Brunswick, New Jersey, Dobbs Ferry, New York, Stratford and Wethersfield, Connecticut–indicated a crossing of a major river: the Raritan, Hudson, Housatonic, and Connecticut, respectively.

A briefly annotated transcription of the itinerary here

follows.[46]

- Brunswick [N.J.] - Mr Lyle, Esqr was an alderman of the town of New Brunswick.

- Woodbridge - Mr Wm Heard. Not further identified among members of a large clan by that name in the Perth Amboy-Woodbridge region.

- Eliz. Town - Mr Woodruff. Samuel Woodruff, a prominent merchant was for many years a trustee of the College of New Jersey .

- Newark - Mr Burr. Rev. Mr. Aaron Burr Sr., president of the College of New Jersey.

- Auquahnock - Mr Marinus, who is not further identified. Acquackanonk is a section of Clifton in Passaic County; there are around a hundred different spellings of the town's name. (Given as Acquackanonk in Becker's volume, p. 2.)

- Hackinsack - Mr [illegible]

- Dobbs Ferry - Tavern. Named after John Dobbs, who bought land in the area around 1700; his descendants ran a ferry. Robert and Mollie Sneden owned a tavern in 1754; Mollie was related to the Dobbs family. (Information was obtained with the assistance of Beatrice W. Agnew, Director of the Palisades Free Library; Alice Gerard, Chair of the Palisades Historical Committee; and the book Palisades and Sneden's Landing, by Alice Haagensen. Letter of 17 August 1995 to the authors.)

- White Plains [N.Y.] - Doctor Graham. Robert Graham, son of Rev. Mr. John Graham (1694-1774), friend of Wheelock.

- Horseneck [Conn.] - Capt. Jabez Mead. Part of Greenwich, where 'one Mead' kept a tavern.

- Stamford - Mr [Abraham] Davenport Esqr, a prominent lawyer, was a half-brother of Sarah Davenport, Eleazar Wheelock's first wife.

- Norwalk - Mr Dickinson. Rev. Mr. Moses Dickenson had been minister of the First Congregational Church since 1727.

- Green's Farms - Mr Buckingham. Then part of Fairfield, Green's Farms is now Westport. Rev. Mr. Daniel Buckingham was pastor of the church from 1741 until his death in 1766.

- Fearfield - Mr Hobart. Fairfield was the birthplace of Aaron Burr Sr. (1716). Rev. Mr. Noah Hobart was pastor of the First Church of Christ for forty years, from 1733 to 1773.

- Stratfield - Mr Ross. The town is now part of Bridgeport. The Rev. Mr. Robert Ross wrote Latin grammars and spelling books. In 1755 he contributed to funds for Wheelock's school.

- Stratford - Mr. Gold. The Rev. Mr. Hezekiah Gold was pastor of the First Congregational Church for thirty years.

- Milford - Mr Prudden. The Rev. Mr. Job Prudden was the first minister of the town. He died in 1774 from smallpox, contracted at a visit to a sick parishioner.

- New Haven - Mr Pierpont. James Pierpont Jr. and Wheelock were friendssince the latter's visits to New Haven as an itinerant preacher in the Great Awakening.

- North Haven - Mr Stiles. The Rev. Mr. Isaac Stiles, minister of North Haven, 1724-1760. Father of Ezra Stiles, president of Yale College from 1777 to 1795. Isaac's younger brother Abel was a Yale 1733 classmate of Wheelock.

- Wallingford - Mr Charles Whittlesey. Not further identified.

- Middlefield - Mr David Miller. The town was the southwestern part of early Middletown.

- Middletown - Mr Eells. The Rev. Mr. Edward Eells was minister of the North Church of Middletown from 1738 until his death in 1771.

- Slepney - Mr Russell. The Rev. Mr. Daniel Russell was minister of Slepney parish (now Rocky Hill) in Wethersfield from 1727 to 1764.

- Glassenbury - Mr Woodbridge. In 1870 the town's name became Glastonbury. The Rev. Mr. Ashabel Woodbridge was minister from 1728 to 1758.

- Eastbury - Mr. Chalker. A small parish (now Buckingham) in the eastern part of Glastonbury had the Rev. Mr. Isaac Chalken as its minister from 1743 to 1765.

- Hebron - Mr. Pomeroy. The Rev. Mr. Benjamin Pomeroy (1704-1784), pastor at Hebron from 1735 to1784.

According to Wheelock, the two Delawares 'left all their Relations & Acquaintance, and came alone, on foot, above 200 miles, and thro' a Country, in which they knew not one Mortal, and Where they had never pass'd before, to throw themselves for an Education upon a Stranger, of Whom they had Never heard, but by Mr Brainerd, and Without any visible Means of Support, but the Charity of Strangers.'[47]

It may here be noted that there frequently is a striking degree of agreement between distances as recorded in Wheelock's letters and in modern tables; the following are taken from the AAA Map 'n' Go 2.0 (CD-ROM):

| From Lebanon Crank (Columbia), Connecticut to -- | ||

| (in miles) | Wheelock[48] | AAA |

| Hebron, Conn. | 'about 5' | 4 |

| Windham, Conn. | 'about 9' | 9 |

| Boston, Mass. | '100 miles' | 94 |

| Hartford, Conn. | 'about 23' | 24 |

| New Haven, Conn. | '60' | 59 |

| Hanover, N.H. | 'near 200' or ‘170’ | 173 |

| Brunswick, N.J. | 'above 200' | 205 |

After their arrival on 18 December 1754, the two boys probably had room and board with the Wheelock family, joining at least five Latin School students. A few weeks later, on 4 January 1755, Wheelock recorded, 'John Pumshire & Jacob Woolley came to Board with me: & they and Ralph [Wheelock's son] went to Live in my Wife's House,'[49] which was located across the road, south of Wheelock's house. It had been part of a real-estate purchase, made in the name of Mrs. Mary Wheelock, Eleazar's second wife, from John English on 22 July 1754.[50]

That they were warmly received by a number of citizens in and around Lebanon Crank is reflected in a list of donations of money, goods, and services that Wheelock recorded during the first two years of their presence. William Chaplin gave deerskin for breeches that were made by Martha and Sarah Wright; Mr. Newcomb gave half a bushel each of beans and potatoes; Mr. Leslie gave two pen-knives; Mrs. Peas promised to spin '14 run of linnen yarn'; Francis Griswold gave a pair of shoes; Dr. John Newcomb gave �6.10.0; Jonathan Trumbull's lady [wife of the future governor of Connecticut] gave an 'Old Great Coat, a Short Bodied Coat, two pair of breeches'; the Rev. Mr. Graham supplied a good homemade '4 run cloth shirt'; others gave a loin hind of mutton, two cheeses of 8 1/2 lbs., two good felt hats, wool for stockings (for which Mrs. James Allen would do the spinning and twisting); and John Ledyard Esq. of Hartford [grandfather of the famous traveller] gave �0.11.6 to the education of the Indian boys.[51]

Another gesture of support was made when at a legal meeting of the members of the parish on 18 November 1755 it was voted 'that if said school [the Indian Charity School] shall be set up, that in order to their regular, comfortable and orderly attendance upon the public worship of God, the boys in said school shall have for their use, the pew in the gallery, over the west stairs in the Meeting House; and further provision suitable for them in said Meeting House shall be made if there shall be occasion.' After Indian girls joined the school in 1761, it was 'voted to allow Mr. Wheelock's Indian girls liberty to sit in the hind seat on the women's side below.'[52]

In the first two years after their arrival, John and Jacob learned to speak, read, and write English. Unfortunately, after about a year and a half, John Pumshire's health began to fail. Wheelock wrote:

. . . when [he] began to decline, and by the Advice of Physicians, I sent

him back to his Friends, with Orders, if his Health would allow it, to

return with two more of that Nation, whom Mr. Brainerd had at my

Desire provided for me. Pumshire set out on his Journey, November

14th. 1756. and got Home [26 January 1757], but soon died. And on April 9th.1757, Joseph Woolley and Hezekiah Calvin came on the Horse which Pumshire rode.

The Decline and Death of the Youth was an instructive Scene

to me, and convinced me more fully of the Necessity of Special Care

respecting their Diet; and that more Exercise was necessary for them,

especially at their first coming to a full Table, and with so keen an Appetite,

than was ordinarily necessary for an English Youth. And with the Exercise of such care . . . I am persuaded there is no more Danger of their Studies being fatal to them, than to our own Children.[53]

John Pumshire and Jacob Woolley had come to Wheelock personally, not to an existing school. However, by the time the next three students came in early 1757, the Indian Charity School had been established.

The originality of Wheelock's plan for his Indian School has been questioned by some, including Marvin D. Bisbee (1845-1913), Class of 1871 and Librarian of the College from 1886 to 1910. Regarding the founding of Dartmouth College, Bisbee wrote, 'Indirectly, at least, its origin may be traced to Bishop George Berkeley. . . . He planned to found a college at Bermuda, in which English and Indian youth should be trained together to furnish satisfactory ministers and missionaries. . . . While there is no record that the founder of Dartmouth consciously adapted the plan . . . the fact is patent that he did so exactly.'[54]

George Berkeley (1685-1753), Bishop of Cloyne, the renowned philosopher, had in 1724 published 'A Proposal for the better supplying of Churches in our Foreign plantations, and for converting the savage Americans to Christianity.' Berkeley's seminary or college would educate Indian youth (by Berkeley called 'young Americans') in ‘religion and learning . . . [to] make the ablest and properest missionaries for spreading the gospel among their countrymen; who would be less apt to suspect, and readier to embrace a doctrine recommended by neighbours or relations, men of their own blood and language, than if it were proposed by foreigners, who would not improbably be thought to have designs on the liberty or property of their converts.' The students to be admitted would have to be 'under ten years of age, before evil habits have taken a deep root; and yet not so early as to prevent retaining their mother-tongue, which should be preserved by intercourse among themselves.' Besides instruction in religion and morality, the students would get 'a good tincture of other learning; particularly of eloquence, history, and practical mathematics . . . [and] some skill in physic [medical practice].' The students would be ready to enter the practical world 'after they had received the degree of master of arts . . . and holy orders in England.' Berkeley's concern was that Spanish and French missionaries 'are making such a progress, as may one day spread the religion of Rome, and with it the usual hatred to Protestants.' Students, 'who upon trial are found less likely to improve by academical studies, may be taught agriculture, or the most necessary trades.' Location in Bermuda added a number of advantages to the plan, which implied that 'the employing American

missionaries for the conversion of America will, of all others, appear the most likely method to succeed.'[55]

Mr. Bisbee drew upon this background in a design for 'a book-plate for the College library, with the shield of the College seal in the centre, surrounded at the four corners with the shield of Berkeley [left upper], representing the intellectual background, the shield of the Wheelocks [left lower] representing the founder, and the shield of the [Daniel] Websters [right lower], representing the refounder [together with the stag's head crest from the coat of arms of the Earl of Dartmouth, right upper], the whole disclosing symbolically the chief sources of the history of our college.'[56]

[1] The North or Second Parish of the Congregational Church of Lebanon, Connecticut (also known as the Second Society or Second Church of Christ of Lebanon), was located in the part of town called Lebanon Crank. In 1804 that was, however, incorporated as a separate town, Columbia. Wheelock and others in referring to their location rarely used the term Lebanon Crank, preferring simply Lebanon.

[2] David M'Clure and Elijah Parish, Memoirs of the Rev. Eleazar Wheelock, D.D., Founder and President of Dartmouth College and Moor's Charity School . . . (Newburyport: E. Little & Co., C. Norris & Co., Printers, 1811), 16.

[3] Together with Benjamin Pomeroy, his classmate at Yale College (and future brother-in-law), Wheelock was the first recipient of the Berkeley Prize, which was awarded to them at graduation in 1733 for excellence in the study of the classics. M'Clure and Parish, Memoirs, 13.

[4] The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed., accepts this spelling.

[5] Ebenezer Selden to Eleazar Wheelock, 25 April 1738, Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections, Ms. 738275; John Gordon to Eleazar Wheelock, 26 February 1755, Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections, Ms. 755176.

[6] Moor�s Charity School Accounts, Daybook, 1767-1772, p. 65 [?], 11 November 1768, Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections (Reel 15 of the microfilm edition of the Wheelock Papers).

[7] Ephraim Peas account in Moor's Charity School 'Accounts,' Ledger, 1760- 1779, p. 8; some pages identified as Ledger B. Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections (Reel 14 of the microfilm edition of the Wheelock Papers).

[8] Examples taken from Moor's Charity School 'Accounts,' Ledger, 1760-1779. A number of account books of Wheelock's schools have been preserved. They supply much information on day-to-day life in Lebanon Crank. Transactions were first entered in a daybook and subsequently collected into individual accounts in ledgers.

[9] Samson Occom, 'S. Occom's account of himself,' p.1. Dated 17 September 1768, the memoir is 26 pages long and measures 6 by 3 and 5/8 inches, uniform in size with other pieces in his 'Journal and Sermons,' Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections.

[10] The stems and leaves of native iris, blue flag (Iris versicolor), growing in streams and swamps.

[11] Wheelock's name had become known throughout New England by his participation, as an itinerant preacher, in the major religious revival of the early 1740s, the Great Awakening. He made two extensive preaching tours: one of Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts (16 October to 16 November 1741); and a second to New Haven, Connecticut (from 7 to 28 June 1742).

[12] Samson Occom, 'Account,' 2-8.

[13] Samson Occom, 'Samson Occom's Journal from Dec. 6, 1743 to Nov. 29, 1748,' in his 'Journal and Sermons.' There is also a typewritten transcription of Occom's diary in three volumes; Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections.

[14] David M'Clure and Elijah Parish, Memoirs, 16.

[15] Eleazar Wheelock to Messrs. Peck, Mason & Austin, 5 November 1766, Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections, Ms. 766605.2; also, Eleazar Wheelock to John Smith, 15 September 1761, Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections, Ms. 761515, and Leon Burr Richardson, An Indian Preacher in England; Being Letters and Diaries Relating to the Mission of the Rev. Nathaniel Whitaker to Collect Funds in England for the Benefit of Eleazar Wheelock's Indian Charity School, from Which Grew Dartmouth College, Dartmouth College Manuscript Series Number Two (Hanover, N.H.: Dartmouth College Publications, Printed by Stephen Daye Press, Brattleboro, Vt., 1933), 178.

[16] Eleazar Wheelock, Book of Accounts, 1726-1750, p. 114. Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections (Reel 13 of the microfilm edition of the Wheelock Papers).

[17] Wheelock conforms to the use of double dating the year for dates before 25 March. The Gregorian calendar of 1582 was not adopted in England and her colonies until 1752.

[18] Franklin Bowditch Dexter, Biographical Sketches of the Graduates of Yale College with Annals of the College History, 6 vols. (New York: H. Holt and Company, 1885-1912), 1:355-356; John W. Stedman, The Norwich Jubilee. A Report of the Celebration at Norwich, Connecticut . . . (Norwich, Conn.: 1859), 284-285.

[19] Eleazar Wheelock to Messrs. Peck, Mason, and Austin, 5 November 1766, Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections, Ms. 766605.2.

[20] Samson Occom, 'Account,' 8-9.

[21] Wheelock speaks of 'ye Tuition of English Boys upon Pay' in a letter to George Whitefield, 1 March 1756; Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections, Ms. 756201.

[22] Old tenor refers to paper money (bills of credit) issued byindividual colonial governments at different times. Connecticut first issued bills of credit in 1709. When the issue of 1740 was called new tenor, the earlier ones became old tenor. Exchange rates between them, or with coins containing gold or silver, varied widely.

[23] Samson Occom, 'Account,' 8.

[24] Eleazar Wheelock, Book of Accounts, 1726-1750, p. 114.

[25] William De Loss Love, Samson Occom and the Christian Indians of New England (Boston, Chicago: The Pilgrim Press, 1899); Harold Blodgett, Samson Occom, Dartmouth College Manuscript Series Number Three (Hanover, N.H.: Published by Dartmouth College Publications [Printed by Stephen Daye Press, Brattleboro, Vt.], 1935); Leon Burr Richardson, An Indian Preacher.

[26] David M'Clure and Elijah Parish, Memoirs, 259.

[27] Eleazar Wheelock to George Whitefield, 1 March 1756.

[28] Eleazar Wheelock to the Rev. Mr. Gillis, Glasgow, 18 April 1764, Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections, Ms. 764268.2.

[29] Eleazar Wheelock to unknown recipient, 1756, Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections, Ms. 756900.1.

[30] Eleazar Wheelock, A Plain and Faithful Narrative of the Original Design, Rise, Progress and Present State of the Indian Charity-School at Lebanon, in Connecticut, Rochester Reprints No. 1 (Boston: Printed by R. and S. Draper, in Newbury-street, 1763), 14.

[31] Eleazar Wheelock to the Connecticut Assembly, 2 May 1758, Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections, Ms. 758302.2.

[32] Eleazar Wheelock to Lord Lothian, 4 May 1761, Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections, Ms. 761304.2.

[33] Eleazar Wheelock to Thomas Foster, 23 March 1763, Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections, Ms. 763223.

[34] Eleazar Wheelock to George Whitefield, 1 March 1756.

[35] Eleazar Wheelock to unknown recipient, 1756.

[36] Wheelock, A Plain and Faithful Narrative, 11. The Rev. Mr. John Sergeant Sr. (1710-1749), a 1729 Yale graduate, was ordained in 1735 (a few months after Wheelock's ordination). He became a successful missionary among the Stockbridge, Massachusetts, Indian day students.

[37] Wheelock, A Plain and Faithful Narrative, 29-30.

[38] Thomas Brainerd, The Life of John Brainerd: the Brother of David Brainerd, and His Successor as Missionary to the Indians of New Jersey (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Publication Committee; New York: A. D. F. Randolph, 1865), 280.

[39] Peter O. Wacker, Land and People: A Cultural Geography of Preindustrial New Jersey: Origins and Settlement Patterns (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1975), 57.

[40] Brainerd, Life, passim.

[41] Brainerd, Life, 280.

[42] Brainerd, Life, 255.

[43] Henry Goodwin Smith to Harold Goddard Rugg, 29 March 1933, and 'Description of Passport,' Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections, Ms. 754900.

[44] Aaron Burr and John Brainerd, Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections, Ms. 754900.

[45] William Buell Sprague, Annals of the American Pulpit, 9 vols. (New York: R. Carter and Brothers, 1857-[1869]), 3:68-72.

[46] Donald William Becker, Indian Place-Names in New Jersey. (Cedar Grove, N.J.: Phillips-Campbell Publishing Co., Inc., 1964), is a first source to check for identification.

[47] Eleazar Wheelock to George Whitefield, 1 March 1756.

[48] Sources of mileage information in Wheelock manuscripts, Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections: Hebron, Ms 767479.1; Windham, Ms. 764503; Boston, Ms.768360.2; Hartford, Ms. 763405.2; New Haven-Hanover, Moor's Charity School Accounts Ledger, 1770, 7 May to 1 October; Lebanon-Hanover, Wheelock to the Rev. Mr. Nicholas Phene, 3 December 1770, Ms. 770653.3; Brunswick, Ms. 756201.

[49] Eleazar Wheelock, 'Minutes and Journal,' 1754-1756.

[50] Deed of sale, office of the Town Clerk, Lebanon, Connecticut, Volume 8:365.

[51] Eleazar Wheelock 'Minutes and Journal,' 1754-1756, 1761-1762, and 1771-1778. Examples taken from the years 1754-1756, passim. Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections (Reel 13 of microfilm edition of Wheelock Papers).

[52] The 150th Anniversary of the Organization of the Congregational Church in Columbia, Conn., October 24th, 1866:. Historical Papers, Addresses, with Appendix (Hartford: Printed by Case, Lockwood, 1867), 51.

[53] Eleazar Wheelock, A Plain and Faithful Narrative, 30-31.

[54] Dartmouth College. General Catalogue of Dartmouth College and the Associated Schools 1769 � 1900, Including A Historical Sketch of the College; Prepared by Marvin Davis Bisbee the Librarian. (Hanover, N.H.: Printed for the College [by the University Press: John Wilson and Son, Cambridge, Mass.], 1900), [25].

[55] George Berkeley, The Works of George Berkeley, D.D. Formerly Bishop of Cloyne, . . . 4 vols. (Oxford: At the Clarendon Press, 1871), 3: 217, 218, 225, 227, 218.

[56] Marvin D. Bisbee, The Dartmouth Bi-Monthly, 2:1 (October 1906), 23. The plate was done by the renowned Boston engraver Joseph W. Spenceley (1865-1908).