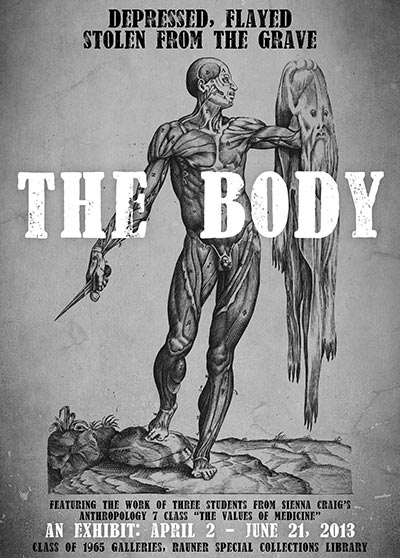

The Body: Depressed, Flayed & Stolen From the Grave

What do Renaissance artists and anatomists, Dartmouth medical students at the turn of the 20th century, and Robert Burton’s famous 1621 treatise The Anatomy of Melancholy have in common? They inspire us to consider the relationship between science, ethics, and humanism in the practice of medicine.

What do Renaissance artists and anatomists, Dartmouth medical students at the turn of the 20th century, and Robert Burton’s famous 1621 treatise The Anatomy of Melancholy have in common? They inspire us to consider the relationship between science, ethics, and humanism in the practice of medicine.

These student exhibits emerge from a First-Year Seminar entitled, "The Values of Medicine: Knowing Bodies, Forming Practitioners, Shaping Institutions." In this course, we use primary materials from the 16th – 21st centuries, located both within the Rauner Special Collections Library and at the Hood Museum of Art, to explore the cultural roots and contemporary expressions of medicine in Euro-American contexts. We contemplated themes of the body, personhood, and the medical gaze by examining 16th century anatomy texts and visiting the anatomy lab at Geisel School of Medicine. We considered what it means to be a “good” doctor by exploring LIFE Magazine photo essays. Midwifery textbooks spanning three centuries instructed us about the gendered nature of medical practice, and links between medicine and social inequality.

Students dove into materials which challenged them to look carefully and read closely across a range of textual and visual mediums. Their final assignment was to curate an exhibit of their own, on a topic of their choice. They rose to this challenge, bringing intellectual inquiry, creativity, and sophistication to the ways they told stories with and through such materials. In addition to the exhibits on display, other projects included: the social life of blood; artistic representations of the objectification of women; a history of Nathan Smith and the founding of Dartmouth Medical school; explorations of anatomical anomalies as "monsters and marvels"; and the collective, social illness narratives invoked by epidemics. At the end of term, all students presented their exhibits and then voted in support of their favorite projects. These three cases of student work emerged as exemplars.

Sienna Craig

Associate Professor of Anthroplogy

The exhibition was curated by Caitlin Zellers '16, Lynn Huang '16 & Regan Haegley '16 from Sienna Craig's Anthropology 7 class "The Values of Medicine" and will be on display in the Class of 1965 Galleries from April 2 to June 21, 2013.

You may download a small, 8x10 version of the poster: ValuesOfMedicine.jpg. You may also download a handlist of the items in this exhibition: Values.

Materials Included in the Exhibition

Case 1. Water Nymphs, Perturbations, and The Devil: Perceptions of Mental Illness Then and Now by Caitlin Zellers ‘16

Take a step back and really think about someone with a mental illness. Can you say that you could look at them in a completely objective way without letting emotion or social norms affect your viewpoint? With depression on the rise, prescriptions of pharmaceutical drug treatments increasing, and recognition of PTSD strengthening, mental illness today has become a prominent social and medical issue. Mental illnesses have always been in the social and medical fields of vision however they have not always been as widely understood and accepted. Today, mental disorders are seen as legitimate biomedical issues often caused by chemical imbalances or physiological defects. The social perception of mental illness had a strong influence in its diagnosis in the 17th century and although this influence has weakened over the last 400 years it has not entirely relinquished its grip. Although both lay and medical perceptions of mental illness have evolved over the past four centuries, it may be surprising to learn how much is still the same. Social perception was deeply intertwined in the way practitioners diagnosed mental disorders in the 17th and 18th centuries and in many ways this is still true today. How can society eliminate the stigma that still exists around mental illness and what will that do to the way doctors diagnose and treat these disorders?

Today, mental illness is generally accepted as a legitimate medical disorder diagnosed and treated according to biomedical standards. It wasn’t until the mid 20th century, however, that this mindset became mainstream. In the 1600’s disorders of the mind were labeled under many general terms such as “melancholy” or “insanity” and were often attributed to supernatural punishment or mystical mischief. Supernatural beliefs led society to believe that water nymphs, witches, and most importantly, the devil, caused most mental disorders. The level of biological knowledge about mental health remained low well into the 1800s as it was still seen as more of a socially based problem. The responsibility of treatment was largely placed on the patient’s personal isolation from societal pressures and their own desire to change. By the end of the 19th century, after the Enlightenment and Scientific Revolution, physicians began to explore physiological causes of mental disease, which eventually led to what would be known today as a more modern biomedical perception of mental illness in the mid 20th century. The medical world, however, still has much to learn regarding mental illness and society has yet to entirely give up the stigma that surrounds it. Mental disorders are often still considered a socially derived problem with no permanent biomedical solution. Although mental illness is not referred to as “lunacy” anymore, societal pressures and perceptions still prevent many cases from being properly diagnosed and understood – in either social or biomedical terms. Furthermore, the way in which physicians diagnose mental disorders has always been intertwined with religion and gender inequality. Today these pressures have changed but physicians are influenced nonetheless by social trends particularly those broadcast in the news media highlighting violence from the mentally ill and suicides.

- Anatomy of Melancholy by Robert Burton (1621) Hickmott 197

- Written in 1621, Anatomy of Melancholy is one of the earliest descriptions of the causes and treatments for “melancholia”, which was a general term for many mental disorders of the time including depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disease. Burton highlighted many of the spiritual connections society held with mental illness and the related diagnoses favored by physicians. Medical professionals quoted Burton’s text for over 100 years.

- Anatomy of Insanity by Maureen Cummins (2008) Presses C915cuan

- Artist Maureen Cummins artistically rendered the diagnoses of mental illness and their differences based on gender from McLean Hospital in Belmont, MA from 1818-1843. The vast majority of diagnoses here stem from social issues such as “business management” for males or “domestic problems” for females. The gender disparity displays the 19th century perception that women were considered more prone to mental distress than men and an all around weaker sex, supporting the patriarchal dominance common in the 19th century. This view displays how societal pressures directly influenced the way the medical world treated mental illness.

- Cases of Mental Disease, with practical observations on medical treatment by Alexander Morison (1828) Rare Book RC465 .M675

- Alexander Morison begins his collection of case studies with the acknowledgement that “the information we possess respecting the clinical treatment of mental disease being very limited” there was a great need for observations of the causes and treatments of mental disease. This collection from Edinburgh, collected under Morison’s scientific observations, shows the beginning of the exploration of mental illness from a biomedical standpoint with a focus on the physiological rather than social or domestic causes of mental illness.

- American Psycho: The Social Construction of Mental Illness in the News Media by Lola Adedokun (2003) DC Hist Honors 2003

- In this contemporary thesis Lola Adedokun explores the perception of mental disease in today’s society, specifically through the news media. What she found is that mental illness is considered less of an alien and extreme malady than in previous centuries but it is still considered a “social disease” deeply entwined in gender, racial, and ethnic constructs.

- Observations on the Deranged Manifestations of the Mind or Insanity by J.G. Spurzheim (1833) Rare Book RC601 .S77. Also available online via Hathi Trust.

- J.G. Spurzheim takes an intellectual leap in 1833 with his division of mental illness into melancholia and mania although he acknowledges the imperfection of a division of this sort because of inevitable overlap. His work takes the observations of the like of Morison and analyzes them to uncover the foundational causes of mental illness. Some connections that he makes are hereditary, age related, and of a nature related to physical trauma. Spurzheim also differentiates “idiotism” at birth from that developing later in life, the first not socially considered as “delirium”, “insanity”, “melancholy”, or “mania”.

- Thesis on Delerium Tremens by Victor Abbot (1859) DA-3, Box 10941

- By 1859 knowledge about mental illness had markedly shifted towards biology and medicalization yet little was still known about the specific mechanisms in the brain that caused these disorders. Victor Abbot found through his studies the connection of mental illness and “inflammatory irritation” and “excited vascular action in the meninges of the brain”. Based on his intimate case studies of patients and through his own experimental treatments he deduced that mental diseases varied based on their causes and each disease is variable in its symptoms and severity.

- The Compleat Melancholik “The Menu of Melancholy” by Lewis Turko (1985) Presses B476turc

- Originally published in the New York Quarterly in 1974 this poem, derived from the explanations in The Anatomy of Melancholy by Robert Burton outlines the extensive list of prospected dietary causes of melancholy and “generally engender gross humours and windy bile”. Containing most meats, seafood, spices, fruits, “sweetings” the poem highlights how little the medical world and society at large knew about the nature of mental illness and depression as it seems as though only vegetables and water were not “windy, and full of melancholy.”

Case 2. Ecce Homo: Behold the Man by Regan Haegley '16

Beginning with Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, the artistic depiction of the “Skin Man” has reappeared throughout the centuries. In this original depiction, the Skin Man is hanging loosely, suspended in the air among other, more abled-bodies. Inspired by this famous work, Andreas Vesalius was first to incorporate the Skin Man in his 1543 anatomical text, where the Skin Man proudly presents his skin, loftily held high. In the other hand, he casually holds his shearing knife, implicitly from his self-skinning. He proudly presents his powerful, still-able body. The Skin Man is reproduced by modern methods using a donated human cadaver for the educational Body Worlds exhibition.

Included in this exhibit, three renowned anatomy books by Andreas Vesalius, Johann Remmelin, and Juan de Valverde integrate humanity-oriented anatomy in educational texts over three centuries. When posed in expressive positions, however, Body Worlds exhibits are criticized for appearing alive, even though this once was the widely accepted norm, even within professional medical textbooks.

- Andreas Vesalius. De Humani Corporis Fabrica. (pp. 164-165). Basil, 1543. Rare Book QM21 .V47 1543

- Vesalius’ compilation of anatomical illustrations also depicts human bodies in varying stages of dissection. Other images comprehensively display the muscular, vascular, nervous, and skeletal systems for instructional use in the medical field. This particular volume includes elaborate backgrounds as settings for the bodies, such as distant cities or a passing rhinoceros. The various settings emphasize the same concept as the expressive body positions: the humanizing of science. The live representations of the bodies preserve their humanity, even in the formally informative context of an anatomy book.

- Juan de Valverde. Anatome corporis humani avctore. (pp. 125). Venetiis: Studio et industria Ivntarvm, 1607. Rare Book QM21 .V356

- The humanization of this famously proud man of muscle was inspired by the original “Skin Man” of Michaelangelo’s self-portrait in the Sistine Chapel. Valverde’s anatomy book includes intricate illustrations of human bodies in varying stages of dissection, all portrayed in expressive, human stances. The muscle man’s ownership and proud display of his own skin and muscle underneath is inspiring in its dignity. His confidence in revealing the usually unexposed powerfully commands respect from the audience despite his vulnerable vitality.

- Michael Spaher and Johann Remelin. Survey of the Microcosme of the Anatomy of the Bodies of Man and Woman. (pp. 3). London: Midwinter and Leigh, 1702. Rare Book QM21 .R4513

- Here, the male anatomy is explored in layers. The unique use of fold-outs in this anatomy book exemplifies the author and artist’s cooperative efforts to convey the depth of the human body. The humanity of the man is conveyed in his pose, his expression and eye contact, and the use of a plant as a flap to cover his genitalia. His expressiveness, connection with the viewer, and the preserving of his dignity demonstrate the humanity expressed in the illustration.

- "Mission of the Exhibitions." Gunther Von Hagens' Body Worlds. Institute for Plastination, n.d. [not available in Rauner]

- While many perceive the purpose of these exhibits to be artistic, the goal of the Body Worlds exhibitions according to the organization’s mission statement is “health education” for the “lay audience.” The personality of the positioning of the exhibits in Body Worlds therefore is comparable to the rare anatomy books because all works included in this exhibit are aimed at education of human anatomy; however, as rare books targeted physicians as audience, the modern exhibitions target a spectrum of “lay audience.” When accounting for variation of familiarity with anatomy, engaged portrayals of the body ensure the exhibitions are relevant to audiences of all educations. Beyond educational purposes, a general appreciation of the human body is enhanced, as the bodies are relatable in their human personalities.

- The larger images of Body Worlds exhibits capture modern adaptations of illustrations by Vesalius and Valverde. Various body positions include acts of skateboarding, playing chess, and more; the personality of the bodies’ positioning contributes, as the mission statement explains, to “help the visitors to once again become aware of the naturalness of their bodies and to recognize the individuality and anatomical beauty inside of them.”

Case 3. The Dirty Doctor: Skull Smashing, Grave Robbing, and Body Snatching by Lynn Huang '16

What do we imagine when we hear the word “doctor”? A neat man in a white coat? A respected healer who saves lives? During the 19th and 20th centuries, when medicine was professionalized in schools and residency programs, the term “doctor” carried darker meanings. Medical students, unable to procure enough bodies for dissection, took to body snatching. In fact, medical schools often turned a blind eye to such nighttime raids. Digging up the dead was a natural prerequisite to healing the living.

Today’s medical students may have moved beyond the grave, but does this shift to legitimate procurement of cadavers make it any easier to cope when they first cut into human flesh? Human corpses and body parts have always held material value: shrunken heads as trophies of war, deformed skeletons as curios. [1] In fact, grave robbing, the practice of stealing valuables from graves, has been a part of human society as long as burial has—recall the tombs of Egyptian pharaohs. The richer the deceased, the bigger the payoff from grave robbing.

Body snatching, the theft of fresh corpses, is closely related to grave robbing. However, whereas grave robbing capitalizes on the body’s possessions, body snatching directly commoditizes the body. Instead of targeting the rich, body snatching focused on corpses belonging to those that would not missed: criminals, paupers, African Americans. The more wretched the deceased, the smaller the risk from body snatching.

Although stolen bodies often belonged to outcasts, some famous cases caused public outcry. In 1878, the body of Senator John Scott Harrison (son of President William Henry Harrison) was discovered by his nephew and son at Ohio Medical College. [2] In the Resurrection Riot of 1788, a mob hungry for medical students swept New York. Medical professionals had to carefully maintain a public persona opposed to body procurement, despite a pragmatic private side that accepted, even encouraged body snatching. It was not until the legalization of human dissection and the establishment of gift programs that medical students gave up body snatching.

Today, students only dissect unclaimed bodies or bodies voluntarily given to science. Medical schools try to prepare students for the first cut, and yet it remains an intensely intimate moment each student must learn to cope with. Even in death, the human body endures as an inviolable, sacred part of self.

Sources for Introduction Text:

- Margaret Lock, Beyond the Body Proper: Reading the Anthropology of Material Life, (Duke University Press, 2007), p. 569

- Raphael Hulkower, “From Sacrilege to Privlege: The Tale of Body Procurement for Anatomical Dissection in the United States,” (The Einstein Journal of Biology and Medicine, 2011), p. 24.

Case Items:

- Constitution and Laws of the State of New Hampshire. Printed at Dover [N.H.] by Samuel Bragg. 1805. NH Dover 345.22 N42 1805

- Strict punishments for “body-snatching,” approved June 16, 1796:

- “Fined a sum not exceeding one thousand dollars” ($15,000 today)

- “Publicly whipped not exceeding thirty-nine stripes”

- “Imprisoned not exceeding one year”

- In comparison, some other punishments:

- Fornication: “Sixty shillings” OR “ten stripes”

- Assault with Intent to Commit Murder: “One hundred stripes”

- Murder: “Death” AND “Dissection” of the Dead Body

- Strict punishments for “body-snatching,” approved June 16, 1796:

- Letter from Five Medical Students to the President and Professors of Dartmouth College. Dartmouth College. 1810. Manuscript 810900.6

- Formal apology from medical students on behalf of their “beloved Instructor,” who went body snatching in local graveyards. Some instances of irony include:

- Citizens “have long been educated, to hold sacred” the “relics of their dead,” implying uproar stemmed not from their actions, but from the citizens’ beliefs

- Vigilance pledged only “as Members of the Institution”—something they may see as separate from nighttime raids

- Will not suffer grave-robbing “to be done, by others,” but only if “in [their] power to prevent it.”

- Formal apology from medical students on behalf of their “beloved Instructor,” who went body snatching in local graveyards. Some instances of irony include:

- Photographs of Dartmouth Medical School Dissection Lab, ca. 1908. Dartmouth Medical School. Circa 1908. Photofile: Medical School -- Dissection

- Private view of dissections, in a basement and an operating theater. Note how nonchalantly the cadavers are displayed: propped against walls, sitting in laps, missing their lower halves, uncovered even when not being used.

- The Body-Snatcher. Robert Louis Stevenson. New York: Merriam. 1895. Val 826 St5 O8. Also available online via Hathi Trust.

- Fictional story that captures body snatching as profane bridge between life and death. Summary:

- Town drunkard Fettes encounters “a great London doctor” named Wolfe Macfarlane. Fettes and Macfarlane share a history of working as medical students in the ‘materials acquisition division’—they supplied bodies. Their duty? “To take what was brought, to pay the price, and to avert the eye from any evidence of crime.” Even if they committed the crime by murdering the innocent Mr. Gray.

- The situation escalates and they are called away on a dark and stormy night to exhume another body, this time a woman’s. It starts raining, their only light goes out, their horse spooks, and the deep ruts of the road jolt their macabre trophy between them. Finally, Fettes and Macfarlane have had enough and uncover their cadaver, only to discover it’s Mr. Gray.

- Fictional story that captures body snatching as profane bridge between life and death. Summary:

- Medical Instruments and Tools Having Belonged to H. O. Smith, Non-Graduate, Dartmouth Class of 1886. Smith O. Henry. Dartmouth College. Realia 191

- Leather bag with glass vials, many of which still possess original labels and contents

- Black leather suturing kit with fish-hook needles and spools for surgical thread

- Two wooden kits of scalpels

- Brass scales with weights

- Black, velvet-lined case with ophthalmologist’s tools

- Body of Work: Meditations on Mortality from the Human Anatomy Lab. Christine Montross. New York: Penguin. 2007. Available in Baker Berry.

- Psychiatrist’s memoir detailing her relationship with her cadaver in medical school. Excerpt:

- Most of us, I think, harbor an ingrained, innate aversion to doing willful harm to the body. Of course, such harm is regularly done: adolescents shoot each other over vapid allegiances, men kick their pregnant wives, children smash beetles to bits under their heels. There is an internal restraint, however, that must be overcome, by rage or fear or sheer will, before we will do harm to a body. And so, watching the flesh coil away, the bone rising above the chest as dust, I feel that feeling you get when you think of the moment your teeth broke as a child or you hear about a fracture in which the splintered bone pierced the skin—an inescapable feeling of wrong…I feel the instinct to place my hand on the cadaver’s arm: This will only hurt a minute. This will be over soon.

- Psychiatrist’s memoir detailing her relationship with her cadaver in medical school. Excerpt: