Revolution!

One hundred years ago, the October Revolution initiated a social and political experiment that unleashed waves of hope, optimism, angst, and horror across the globe. The initial excitement of artists and intellectuals eager for a new world turned to despair as the realities of a new form of tyranny became manifest.

“Revolution!” draws on Rauner Library’s rich collections to show how the products of the Russian Revolution expressed the varied reactions to the rise of communism.

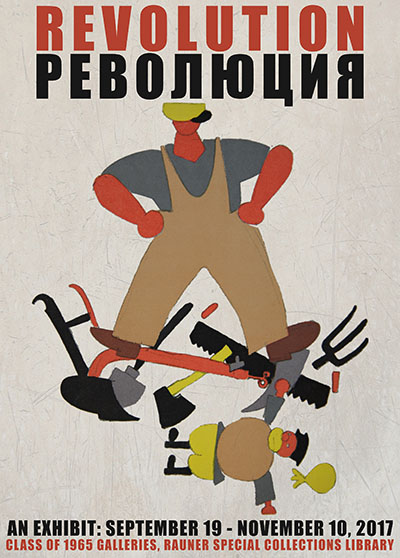

The exhibit was curated by Jay Satterfield and Wendel Cox will be on display in the Class of 1965 Galleries from September 19th through November 10th, 2017.

You may download a small, 8x10 version of the poster. You may also download a handlist of the items in this exhibition: Revolution!

Materials Included in the Exhibition

CASE ONE

Glorifying the Revolution

The Russian avant-garde felt an initial freedom from what they saw as the stultifying effect of bourgeois patronage. Artists saw their roles changing directly after the revolution. Many embraced the ideals of communism and sought to create an art form that was “from” the proletariat. The results were an odd mix of propaganda and some of the most innovated designs of the early 20th century. As the realities of Soviet oppression set in, what once appeared to be spontaneous, unbridled expressions of freedom became complicated by a complicit support for a tyrannical regime. It had the air of propaganda all along, but it transformed from propaganda created out of a sense of hope, to propaganda selling a false promise.- La cinema en URSS. [Cinema in the USSR.] Moscow: Voks, 1936. Rare PN1993.5 R9 S614 1936

- Like many propaganda pieces, the primary audience for this exploration of Soviet cinema was outside of the Soviet Union.

- Samuil Marshak. Mister Tvister. Moscow: Molodais Gvardia, 1933. Rare PG3476.M3725 M57 1933

- Vladamir Maiakovsky. Dlia Golosa. [For the Voice.] Berlin: R.S.F.S.R., 1923. Rare PG3476.M3 D57

- These poems were meant to be read aloud. Eli Lissitzky applied his constructivist aesthetic to the book to use typography to create emphasis for the reader.

- Iakov Chernikhov. Konstruktsiia Arkhitekturnykh i Machinnykh Form. [Construction of Architectural and Machine Forms.] Leningrad: Izdanie Leningradskogo obshchssetva arkhitektorov, 1931. Rare NA2340 C5 1931

- Iakov Chernikhov. Arkhitekturnye Fantazii. [Fantastic Architecture.] Leningrad: Izdanie Leningradskogo obshchssetva arkhitektorov, 1933. Rare NA2760.C45

- These two books of conceptual architectural designs are the work of “not the connoisseur” but the “artist-constructor.”

CASE TWO

Hope and Despair

Two of these books are designed to inspire the world through an aggressive assertion of the economic benefits of communism. The Struggle for Five Years in Four uses “Isotypes” to present data visually and graphically express economic progress. Artist Aleksander Rodchenko uses related constructivist techniques in Ten Let Uzbekistan to show the benefits of Soviet rule.

Throughout Stalin’s programs to eliminate undesirable elements of society, Rodchenko maintained a copy of his work on Uzbekistan. He used India ink to erase from history those murdered by Stalin. When artist Ken Campbell found this defaced copy in the 1990s, it inspired his monumental tribute to Rodchenko that captures the despair wrought by a brutal regime.

- Ken Campbell. Ten Years of Uzbekistan: A Commemoration. London: Ken Campbell, 1994. Presses C155cat

- The Struggle for Five Years in Four. Moscow: State Publishing House of Fine Arts, 1932. Rare HC335 S78 1932

- 10 Let Uzbekistana SSR. [Ten Years of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Uzbekistan.] Moscow: Gos. izd-vo izobrazitelʹnykh iskusstv, 1934. Rare DK941.5 D47 1934

Hope and Internationalism

The Soviet Union was a source of hope to millions around the world, many of whom saw in the Russian Revolution a vision of their own future. Some Americans, like the novelist Theodore Dreiser, traveled to Russia and reported positively on their experiences. Revolution was also exported in print and image. The works of Lenin were available in inexpensive editions which, in some instances, found their way into the hands of young revolutionaries, including Dartmouth’s Budd Schulberg, who would later be a friendly witness for the House Un-American Activities Committee and win an Academy Award for On the Waterfront. Even works originally intended for street display, like placards created for the Russian Telegraphy Agency, might be offered as revolutionary visions for Anglophone and Francophone nations and their colonies. Others, like the acclaimed and widely-influential Russian poet Alexander Blok, presented a more ambivalent vision which offended both revolutionaries and reactionaries alike.

- Theodore Dreiser. Dreiser Looks at Russia. New York: H. Liveright, 1928. Despite its sympathetic account, and Dreiser’s wild popularity in the USSR, his Dreiser Looks at Russia was suppressed in the USSR throughout the Soviet era. Rare DK267.D7

- Vladimir Illyich Lenin. The Revolution of 1917: From the March Revolution to the July Days; The Collected Works of V.I. Lenin, Volume 20. New York: International Publishers, 1929. From the library of Budd Schulberg. Schulberg DK254 L3 A254 1929 bk1

- Vladimir Illyich Lenin. The Period of War Communism (1918-1920); V.I. Lenin, Selected Works, Volume 8. New York: International Publishers, [1937]. From the library of Budd Schulberg. Schulberg DK254 L3 A254 1937

- Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Blok. Dvienadtsatʹ. [The Twelve.] Petersburg: "Alkonost," 1918. Rare PG3453.B6 D8 1918

- Blok regarded this verse account of twelve Bolshevik soldiers marching through a snowy Saint Petersburg as his finest work. Blok died in 1921, unable to take advantage of permission to seek medical care abroad. His friend, the poet Maksim Gorky, pressured Soviet officials for his release, warning they risked responsibility for the death of Russia’s greatest poet.

- Russian Placards, 1917-1922. 1st part / Petersburg Office of the Russian Telegraph Agency (ROSTA) = Le placard russe, 1917-1922. Première série / Agence thélégraphique [sic] russe (ROSTA) à Pétersbourg. Petersburg: Petersburg Branch of the News of the All-Russia Central Executive Committee ("Isvestia VCIK"), 1923. “Agitation for work-cooperation. The workman stands triumphantly before the implements of industry; at his feet lies a marauder vanquished by the system of cooperation.” Rare DK265.R8342 1923

CASE THREE

Writing the Revolution

There are many accounts of 1917, whether prepared by eyewitnesses or offered after the fact. Revolutionaries and reactionaries alike wrote for posterity, to persuade, and to rally their allies and reveal the crimes of their adversaries. Americans John Cushing Varney and Thomas L. Cotton interspersed quotidian and historic events in their accounts of 1917, while the American journalist John Reed rhapsodized revolution and actively worked for its success. Others, like Socialist Revolutionaries Catherine Brezhkovsky and Isaac Nachman Steinberg, wrote of triumph, unease, and despair. Even a decade later, the effort to stage a play in London’s West End examining the Revolution might still earn the Lord Chancellor’s censure purportedly in part for its offense to the Russian émigré community.

- The Papers of Thomas L. Cotton (1891-1964). MS 632, Rauner Special Collections, Dartmouth College Library.

- John Cushing Varney. Sketches of Soviet Russia Whole Cloth and Patches. New York: N. L. Brown, 1920. Alumni V431s

- Ekaterina Konstantinova Verigo Breshko-Breshkovskaia. The Little Grandmother of the Russian Revolution: Reminiscences and Letters of Catherine Brezkhovsky. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1918. Rare DK254.B7 A5 1919

- Brezkhovsky, a member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party and later fierce opponent of the Bolsheviks, once replied to an imperial prosecutor’s query: “My occupation? Revolution.”

-

George Constantine Guins. Sibirʹ, Soiuzniki i Kolchak : Povorotnyĭ Moment Russkoĭ Istorii, 1918-1920 g.g. : Vpechatlieniia i Mysli Chlena Omskago Pravitelʹstva. [Siberia, the Allies and Kolchak: the turning point of Russian history, 1918-1920: Impressions and thoughts of a member of the Omsk government.] Pekin: Tipo-lit. Russkoĭ dukhovnoĭ missii, 1921. Rare DK265.4 G8

-

This memoir of resistance to the Bolshevik Revolution in Siberia catalogs struggles within the forces who sought to displace the Bolsheviks.

-

- Isaac Nachman Steinberg. Ot Fevralia po Oktiabr' 1917g. [From February to October 1917.] Berlin-Milan: Izdatel'stvo “Skify,” [1919]. Red Room DK265 .S737

-

Ubīĭstvo Tsarskoĭ Sem'i i eia svity: offitsīal'nye dokumenty: Prilozhenīem Fotograficheskago Snimka Rospiski Predsiedatelia Ural'skago “Sovdepa” v “Poluchenīi” Byvshago Tsaria i ego Sem'i. [The murder of the royal family and its suite: official documents: with an attached photograph taken from the list of the predecessor of the Uralsk “Sovdep” to “receive” the former tsar and his family.] Konstantinopol': Izd-vo "Russkaia Mysl'," 1920. Rare DK258.U2

-

Hubert Griffith. Red Sunday: A Play in Three Acts; with a Preface on the Censorship. London: G. Richards and H. Toulmin, 1929. Memorable not only for John Gielgud’s turn as Leon Trotsky, Red Sunday in print is prefaced by a satirical perspective of a visitor from the imaginary isle of Ping-Pang-Bong who decries British censorship. Williams/Watson PL5526