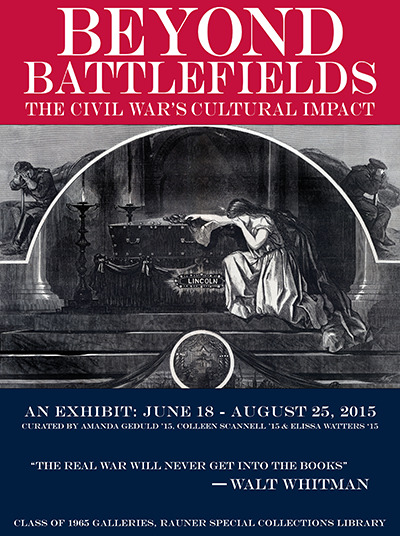

Beyond Battlefields: The Civil War's Cultural Impact

Although Walt Whitman famously claimed “the real war will never get into the books,” the American Civil War called forth a vast range of literary responses, in genres as diverse as poetry, popular song, novels and other prose genres. Much of that literature, however, did in fact not appear in books, but in magazines, newspapers, and letters. These texts did not just respond to the war; they also intervened actively in shaping its cultural meaning. This exhibit, curated by students from Colleen Boggs’s English 72: Civil War Literatures, provides three case studies of the Civil War’s cultural impact. We invite you to examine how the verbal, textual, visual and auditory connected the homefront to the battlefront, and changed Americans’ views of their country and of themselves.

Although Walt Whitman famously claimed “the real war will never get into the books,” the American Civil War called forth a vast range of literary responses, in genres as diverse as poetry, popular song, novels and other prose genres. Much of that literature, however, did in fact not appear in books, but in magazines, newspapers, and letters. These texts did not just respond to the war; they also intervened actively in shaping its cultural meaning. This exhibit, curated by students from Colleen Boggs’s English 72: Civil War Literatures, provides three case studies of the Civil War’s cultural impact. We invite you to examine how the verbal, textual, visual and auditory connected the homefront to the battlefront, and changed Americans’ views of their country and of themselves.

The exhibit was curated by Amanda Geduld ’15, Colleen Scannell ’15, and Elissa Watters ‘15 from Colleen Boggs’s English 72: Civil War Literatures. The exhibit was on display in the Class of 1965 Galleries from June 18 to August 25, 2015.

You may download a small, 8x10 version of the poster: BeyondBattlefields.jpg. You may also download a handlist of the items in this exhibition: Beyond Battlefields.

Materials Included in the Exhibition

Case 1. Women in the Civil War

Women of the American Civil War

During the American Civil War, visual depictions of women situated the female body in a variety of realistic, imagined and metaphorical spaces and contexts. Representations of women as the emotional bearers of grief, as protectors of the home and its comforts, as participants in the war, and even, at times, physical embodiments of the war, are among the many visual tropes that prevailed at the time. The many positive and negative, complementary and paradoxical depictions of women betray the complexities confronted by men and women during the Civil War. These iconic images relocate onto the female body such psychological struggles as crises regarding widespread death, displaced homes, and questions of participation in the war effort. They also played a fundamental role in refashioning female roles and identifies in the years during and shortly following the War.

- Henry C. Work. Grafted into the Army. Chicago: Root & Cady, c. 1862. Sheet Music SC 703

- The Popular Refrain of Glory, Hallelujah: as Sung by the Federal Volunteers throughout the Union. Boston: Oliver Ditson & Co., 1861. Sheet Music 699

Women at Home

Long a prevailing image of the home, women continued to mark and represent domesticity throughout the War. As young men left for the battlefield, the home became a place of consolation, a continual reminder of peace, love and comfort fostered through cherished memories and souvenir packages. The trope of the domestic female who protected, nurtured, and cared for the home (both in man’s presence and in his absence in war) located women at the center of the image of home.

Women in War

Patriotic envelopes created during the war demonstrate the wide range of iconic images produced during the war. The selection on display here shows a variety of depictions of women, with a focus on women as participants in the war and its efforts. The image of Virginia lighting the cannon of secession before which she stands contains a perplexing message of female involvement and martyrdom. Similarly troubling is an image of the woman as the victim of the secession serpent. The final two envelopes address issues of the homefront becoming a battlefront through the production of wartime necessities and presence of death within the home or family.

- Selection of Civil War Patriotic Envelopes. Iconography 1251

- C.A. White. Mother, Take Me Home Again. Boston: White, Smith & Perry, c1869. Sheet Music 744

Women in Mourning

Published in Harper’s Weekly, perhaps the Union’s most popular and widespread periodical of the time, just weeks after President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination on April 16, 1865, this image illustrates the woman as a bearer of grief. On a metaphorical level, the woman represents Columbia mourning for the entire nation (even one still divided) over the death of Lincoln, who had become a representation of the Civil War, the fight to save the Union, and the nation itself.

- Harper’s Weekly, April 29, 1865.

Case 2. The Civil War in Hanover and Surrounding Areas

The Civil War greatly affected the entirety of the United States of America. Although the vast majority of the battles did not reach as high as New England, there was nevertheless a dramatic effect on the home front. The documents you see here offer a glimpse into our homefront: the involvement of Hanover and the surrounding areas of New Hampshire in the Civil War, and the effect that the war had on the Upper Valley.

- Names and Record of all the Members who Served in the First N.H. Battery of Light Artillery during the Late Rebellion, from September 26, 1861, to June 15, 1865. Manchester: n.p., 1884. NH Manchester 1884a

- This document includes members of the First New Hampshire Battery Light Artillery, along with a history of the military unit throughout the war. It is a way to honor those who fought bravely, and preserve their memories forever.

- Abraham Lincoln, selected letters, 1848-1865. Manuscript 848324

- Rauner is fortunate to have numerous letters written by Abraham Lincoln in its possession. Included here is one written to Amos Tuck that endorses the appointment of a new Deputy Naval Officer. Although this is more of an example of a national response to the war, it nevertheless has some local ties with Tuck’s involvement.

- Samuel Penniman Leeds. Remarks Made by the Pastor in “The Congregational Church at Dartmouth College,” on the Sunday (March 9, 1862) after the President’s Emancipation Message. [N.P., N.D.] D. C. History E453 .L456 or Alumni L517r

- These remarks made by the pastor at Dartmouth celebrate the Emancipation Proclamation shortly after its issuance; the pastor remarks how proud he is to be alive during such an “epochal occasion.”

- Gilbert J Robie, selected letters, 1834-1863. Manuscript 862654

- Rauner has an incredibly vast collection of letters written during the Civil War from or to people in New Hampshire. The top letter is from Gilbert Robie, a member of the 15th New Hampshire Regiment, to his wife in Canaan, New Hampshire.

Case 3. Sounds of the Civil War

If you were to explore the history of Civil War prisons what would you expect to find? Photographs? Journal entries? Letters? Or perhaps songs and prayers? You would certainly not expect to find a clip on YouTube, a podcast on iTunes, or a blog. EvanKutzler argues that while written accounts of what occurred in prisons during the war are important, so too is the “sensory history.” He believes sound “further humanizes social history” so he studies the role sound plays in captivity, arguing that prisoners listened for noises to better understand their current and future conditions. Furthermore, sound and silence were utilized as an instrument of power for both the prison guards and the inmates. By looking at Civil War prisons we can examine the means by which we learn and understand history.

Quick Facts

- About 674,000 people were held captive during the war

- About 30,000 Union Soldiers died in Confederate Prisons

- About 26,000 Confederate soldiers died in Union Prisons

- About 1 out of every 7 soldiers (and some civilians) were captured

- African American Union soldiers were usually not imprisoned—they were immediately killed or enslaved

Listen to the War

Read each letter and then listen to the recordings of General Neal Dow’s journal entries from his time Libby Prison (go to /library/rauner/exhibits/civilwar_audio.html or click on the QR Code) What new pieces of the past can be pieced together through sensory history? What are we losing when we cannot obtain such a sensory history and how else can we successfully retrace the sounds of the Civil War?

- Stereoscope view of Libby Prison, Richmond, ca 1865. Iconography 708

- A photographic reproduction of one of the most infamous prisons of the Civil War, which was originally created as a temporary prison, yet ended up holding 1,000 Federal officers by winter 1863-1864. The prison had incredibly scarce resources.

- Warren Lee Goss. The Soldier’s Story of His Captivity at Andersonville, Belle Isle. Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1868. 1926 Coll G67s 1868 c.2 or available online.

- Robert H. Kellogg. Life and Death in Rebel Prisons. Hartford: L. Stebbins, 1867. 1926 Coll K449

- Susan Lord Hayes to Hannibal Hamlin, [1864], retained copy. And Hannibal Hamlin, Bangor, ME, to Susan Lord Hayes, South Berwick, 19 October 1864. Manuscript 002043

- This is a letter from Mrs. Hayes to Hannibal Hamlin, requesting the release or exchange of her son, Brigadier General Joseph Hayes, from a Confederate prison in Salisbury, North Carolina. Hamlin’s reply is included as well.

- Oren G. Colby, selected letters, Point Lookout, MD, 10 January 1863 to 28 March 1864. Charles W. Wilcox, Camp Columbia, S.C. to Mother & Friends, 7 December 1864, typescript transcription. MS-967 (a full finding aid is also online.)

- These letters are from a collection of twenty-one letters to family members from Union prison guards asking for various supplies and describing what they are sending home. They also describe the Confederate prisoners they were guarding and propose ideas for the future of the prison.