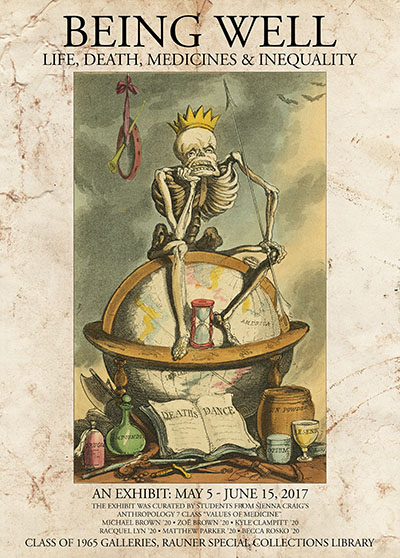

Being Well: Life, Death, Medicine, & Inequality

“Illness is the night side of life,” writes Susan Sontag, “A more onerous citizenship. Sooner or later, each of us is obliged … to identify ourselves as citizens of the kingdom of the sick.” But what does it mean to be ill? How do individuals, families, communities, and health care practitioners navigate passages between wellness and illness? How does access to medicines and other therapies – be they “traditional” or “modern” – shape these decisions? What does socioeconomic inequality have to do with this? And what do we do when medicine can’t save our lives?

These student-curated exhibits speak to these questions. Explorations into good lives and good deaths; plants, people and medicines; and illness narratives as inflected by race in America, the work in these displays emerged from ANTH 7.02 The Values of Medicine. This First-Year Seminar taught by Prof. Sienna Craig is dedicated to exploring such questions through in-depth engagement with Rauner Special Collections.

The exhibit was curated by Michael Brown ’20, Zoë Brown ’20, Kyle Clampitt ’20, Racquel Lyn ’20, Matthew Parker ’20, and Becca Rosko ’20; it is on display in the Class of 1965 Galleries from May 5, 2017, to June 15, 2017.

You may download a small, 8x10 version of the poster: BeingWell.jpg. You may also download a handlist of the items in this exhibition: BeingWell1.pdf.

Materials Included in the Exhibition

Case 1. Cartoonist Found Dead in Home. Details are Sketchy. By Becca Rosko and Kyle Clampitt.

Through a selection of 19th century European texts and illustrations, this exhibit explores the psychosocial shift in the image of death and its representation in popular culture. During the 19th century, death was much more a part of everyday life than it is now, due to poor living conditions and limited medical practices. The fact that it was a common occurrence gave rise to a wealth of death-based humor and satire in literature. By the 20th and 21st centuries, as basic public health standards increased and mortality rates decreased, the topic of death became more socially taboo. The 19th-century books used in this exhibit demonstrate satire through a lighthearted representation of skeletal cartoons. By the 21st century, as revealed in the artist book used in this exhibit, we see a a struggle to accept the inevitability of death or death framed as failure.

The reality of death also prompts reflection on what it means to live a good life. The second part of this exhibit explores this question: What does it mean to live a good life? A handbook offers advice to young gentlemen. The Dance of Life, an epic poem about living, illustrate social ideals about how individuals should conduct themselves in order to achieve a ‘sounder life.’ Throughout the 19th century, living a good life was often defined in terms of having a high moral standard and a good character, as well as adhering to religious practice, which at many times went hand in hand. But what happened if these codes of moral conduct went unheeded? This poses another question: Does living a ‘good life’ justify and lead to a ‘good death’?

-

T. S. Arthur. Advice to Young Men on Their Duties and Conduct in Life. Boston: Phillips, Sampson, 1855. 1926 Coll A73ad

-

This text is a guide for young ‘gentlemen’ of the mid 1800s in the hopes of living a rewarding life with respect to family, friends, self-education, religion, and health. It aimed to help young men learn to take care of themselves and ultimately live a good life. In the book’s conclusion, we learn that a good life would only be achieved if readers followed and reflected on the truths within the handbook. In the 19th century, the responsibility for positive self-representation in society was therefore determined by publicly affirmed displays of moral conduct, rather than individual or personalized beliefs about how one should express oneself.

-

-

Martha Hall. Living (II). Orr's Island, Me.: M. Hall, 2002. Presses H166hali

-

This handmade 21st-century accordion-fold artist book expresses the grim possibility of death by cancer. For the purposes of this exhibit, it represents how death has become something we try to avoid rather than face in contemporary times. Living (II) is powerful. Its concise form highlights the stark distinction between life and death, a battle either won or lost. The term “survivor” simply intensifies the bold line separating those who win and lose battles against cancer. This representation of death is morbid and solemn, equating cancer with a ‘bad death.’

-

-

Hans Holbein. Imagines Mortis. Coloniae: Apud haeredes Arnoldi Birckmanni, 1557. Rare N7720.H6 I434 1557

-

Hans Holbein, a brilliant artist of his time, created this little book which demonstrates society’s impressions about death. This 16th-century text introduces satirical social commentary about death, and sparks the creation of a 19th-century version of this same text, in English translation. Through his elaborate drawings, Holbein is able to satirize mortality by curating different ways death encroaches on the living. His drawings personify death. Humanized skeletons exist casually alongside the living.

-

-

Hans Holbein and Wenceslaus Hollar. The Dance of Death. London: Printed for J. Coxhead, 1816. Illus H691d

-

The Dance of Death is an expanded interpretation of Imagines Mortis with English descriptions and lively color illustrations. The color helps elaborate on earlier portrayals of the satirical image of death. Indeed, the depiction of death becomes cartoonish and almost jovial. Perhaps expressing death in these cartoon satires reveals something about how death in the 19th century was a relatively expected, if not uneventful, part of everyday life. The skeletons within the illustrations act as if they are alive, reminding us that death is always around the corner.

-

-

William Combe and Thomas Rowlandson. The English Dance of Death: From the Designs of Thomas Rowlandson, with Metrical Illustrations, by the Author of "doctor Syntax.". London: Printed by J. Diggens 1815. Illus R796ce

-

These books show the satirical representation of death in the 19th century in Britain. Emulating Han Holbein’s 16th-century illustrations, Thomas Rowlandson, a late 18th – early 19th-century artist, illustrates these texts. The images depict an array of ways that Death, personified as the Grim Reaper, comes to collect living children, royalty, laborers, and others. Published around the same time as The Dance of Death (itself a recreation of Imagines Mortis), these texts follow a storyline based on the universality of death and how it connects everyone. The books are satirical because the skeletons are personified in a way that reflects death as something more commonly encountered and less feared than it is today.

-

-

William Combe and Thomas Rowlandson. The Dance of Life: A Poem. London: Published by R. Ackermann, 1817. Illus R796cd

-

This book represents life, the counterpoint to death that The English Dance of Death (V. I and II) depicts. The illustrations reveal laborers, children, royalty and others living life without constant worry. This, in turn, suggests that following a strict regimen for living, such as the one presented in Advice to Young Men, may not be necessary to live a ‘good’ life. The poem conveys that we should take pleasure in life’s daily activities and live without the fear of death constantly looming over our shoulders.

-

Case 2. The Color of Medicine: Race in Patient Narratives. By Michael Brown and Racquel Lyn

In November 2015, a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association reported that African American children were 80% less likely than white children to be prescribed analgesics when presenting identical symptoms of appendicitis. This medical “fact” helps to quantify a deep-seated racial bias that can be present in the practice of medicine, and that has impacted the ways black patients tell their stories of suffering. Throughout U. S. history, racism and social stigmas have distorted the patient narratives of people of color. In this exhibit, we bring to light rare personal accounts from black patients during the era of slavery and Jim Crow. These stories exemplify the cultural mistrust that can exist between doctor and patient across divides of race and ethnicity – divides that clearly persist to this day.

This exhibit explores the complex reality of how patient narratives are impacted by race and ethnicity in a historical context. The translucent vellum paper that covers some items in the display serves as a metaphor for the many layers of racism and ignorance that one must look past when attempting to bear witness to the realities of history. However, if one looks closely and carefully enough, if one looks beneath the surface, it is possible to see a deeper or different truth. This truth is representative of the choice one makes each day, to either accept a one-dimensional view of medicine or to delve beneath the surface and gain a better understanding of the historical contexts and lived realities of underprivileged patients. This exhibit reveals some of the less known experiences of African Americans in relation to contemporary medicine, and helps the viewer understand the legacy of race and health inequality, amongst other issues, in black communities.

-

Noah Fabricant and Heinz Werner. A Treasury of Doctor Stories by the World’s Great Authors. New York: F. Fell, 1946. Caldwell 581

-

“A Negro Doctor in the South” is one of the short stories in this collection, written in the Jim Crow era by a white author. The story tells the tale of a black woman being treated by a black doctor named Kenneth, who must deal with constant discrimination in his profession because, as the text states, “No negro doctor, however talented, was as good as a white one.” When a white doctor refuses to allow his patient life-saving treatment, Kenneth must resort to threats of violence in order to save the patient’s life. This story shows that even in the 1940s, during an era of legal segregation, there was an awareness of the struggle minorities faced in accessing quality health care. Yet this awareness focuses on the entertainment value of such a tale, and precedes any major legislative action to address Jim Crow by nearly 25 years.

-

-

Frederick Douglass. My Bondage and My Freedom. New York: Miller, Orton & Mulligan, 1855. Rare E499.D738 1855

-

In his autobiography, Frederick Douglass laments the death of his mother. He recounts how, after her long-term illness, “The bond-woman lives as a slave and is left to die as a beast; often with fewer attentions than are paid to favorite horse.”

-

-

William Thayer Smith. Manuscript Diary. March 24, 1877- August 19, 1877. Codex MS 877224

-

This diary from William Thayer Smith details the treatment of his father, an older white male, in the mid-late 1800s. In it, he describes both the earnest efforts of the doctor, who “does all he can” to care for and comfort the elder Smith, and the role of the doctor, who is summoned to be a constant assistant. This text presents a sharp contrast to the experiences of terror described by black patients recounting their interactions with white doctors during this same time period.

-

-

Harriet Jacobs. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Boston: For the Author, 1861. Rare E444.J17 1861

-

Selections from the autobiography of Harriet Jacobs, a slave, reveal her deep fear towards her doctor. After the birth of her child, Harriet’s doctor (who was also her owner) assured her how pleased he was with the survival of her newborn daughter, as it ensured the growth of his “stock.”

-

-

John Brown. Slave Life in Georgia. Savannah: Beehive Foundation, 1991. Presses S859brp

-

A slave named John Brown writes in 1855 about his experiences from the time he was captured until his death. In this text, he recounts the many times he was abused by a doctor who repeatedly performed experiments on him to practice treatments for common diseases and infectious outbreaks that were occurring.

-

-

William C. Reynolds. Reynolds's Political Map of the United States. New York: Reynolds and Jones, c1856. Evans Map Room Special G3701.E9 1856 .R41

-

This map made by William Reynolds immediately precedes the Civil War, and marks rigidly the lines of conflict between regions where slavery was condoned and relative spaces of African American “agency” in our land of “liberty.”

-

Case 3. From Authoritative to Alternative: Plants and Food as Medicine. By Zoë Brown and Matthew Parker

For centuries, people have made use of home remedies and methods of healing that rely on plants and food as medicine. Almanacs, advertisements, journals, and other written texts have, throughout history, documented the ways people have sourced medicine from the natural environment. Yet at the dawn of “modern” medicine, just how prevalent was the use of botanical remedies? Was food viewed as a source of medicinal value? How did concepts of nutrition contribute to the practice of medicine? How did these plant and food forms of medicine alter or influence society’s ability to heal itself, particularly as the authority of the biomedical doctor increased? This exhibit explores the history of plants and food as medicine and their transition from a widely-accepted form of medicine to a healing “alternative,” as they are known today.

This exhibit tells this story in three parts. The first section examines foods and plants that were widely supported by medical professionals from the 15th - 17th centuries, but depicted in a non-scientific, almost mythological manner. The second section focuses on an overlapping period of history (16th – 19th centuries) in which botanical and nutritional healing modalities gained medical authority through the endorsement of accredited physicians. The third section illustrates the transition of this healing modality from an accepted and legitimized tradition to an “alternative” practice from the 17th century to the present. Using a variety of sources including illustrated and artistic works, field guides, and herbals, this exhibit takes viewers through this transformation, shedding light on the intersection of authoritative medical knowledge and traditions of plant and food-based healing.

-

Peter Treveris. The Grete Herball. London: Peter Treveris, 1526. Rare QK99.G7 1526

-

This book is actually a compilation of many different excerpts from other works that Peter Treveris pieced together in the early sixteenth century. Organized alphabetically, the Grete Herball references hundreds of herbs and minerals, including where they can be found in nature, and potential medical uses for each. As shown on this page, Treveris describes each substance as either “hote” or “colde,” a designation that is most commonly associated with Asian and Latin American medical traditions today. Because of its large size, this book is intended not for field use but rather as a reference. The language and images in the book would have been comprehensible to an educated lay reader.

-

-

Johannes von Cuba. Ortus Sanitatis. Strasbourg Johann Priuss, 1497. Incunabula 160

-

On this page of Ortus Sanitatis, an herb known as mandrake is depicted. It comes from the Mandrogara plant family. Although the plant truly exists in nature, the illustration reveals it as a mythical substance. It was believed that the mandrake root, once pulled out of the ground, would emit a screech so piercing that it would kill the person who uprooted it. The author offers a solution to the reader by suggesting that they bring a dog to pull out the root, thus allowing the individual to plug their ears throughout the process of harvest.

-

-

Andrew Boorde. Breviarie of Health. London: Thomas East, 1587. Rare R128.6.B6

-

This small book was presumably constructed for field use by physicians or healers when they needed a quick herbal reference. The book is organized into chapters, each of which is titled with a specific disease or disorder followed by likely causes and remedies. Andrew Boorde, the author and a self-described “Doctor of Physicke,” begins the piece with, “A Prologue to Physicians,” illustrating that botanical knowledge important to the medical field, and that this book was intended for professional rather than everyday use.

-

-

William Barton. Vegetable Materia Medica. Philadelphia: M. Carey & Son, 1817-18. Rare QK99.B33 1817

-

Written by a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, this text reflects a painstaking effort to compile an encyclopedic botanical reference. The book includes beautiful drawings and provides a detailed description of the natural features of the plants themselves, along with their medicinal properties. This source seems written for an academic audience, an intention supported by its size, use of technical language, and ambitious scope. In the larger context of its time period, this text exemplifies a moment in which the academic world legitimized the use of plants as medicine via scholarship on the subject.

-

-

Pierpont F. Bowker. Indian Vegetable Family Instructer. Boston: Bowker, 1836. Rare RS171.B6

-

This herbal is very clearly intended for common use. Here, we see a clear shift from the authoritative knowledge of the medical doctor governing health to the power of well-being given to literate laypeople. The text emphasizes that health is central to happiness. It focuses on the consequent importance of the ability for a person to be his own doctor. As can be seen in these pages, each plant or food is listed with its practical healing properties briefly explained beneath it. Later in the text, an entire section is devoted to recipes for specific ailments.

-

-

John Archer. Every Man His Own Doctor. London: John Archer, 1673. Rare R128.7.A37

-

This text also encourages the common person to seek out his or her own preventative and curative healing measures from the natural environment and in the food he or she chooses to eat. Like other similar guidebooks, it is organized meticulously, with extremely detailed descriptions of the preparation, purpose, and proper usage of the substances it examines. Although the text is legitimized by its author’s profession, it should be noted that the text was sold from the author’s house. Although empirical, there is very little research-based evidence cited in the book. It is made with a practical purpose in mind. In this text, we begin to see a movement toward seeing herbal healing traditions as “alternative.”

-

- Chinese Herbal Medicine Bottle.

-

On the back of this contemporary Chinese herbal medicine product, we see the modern depiction of what is considered “alternative” medicine in the biomedical world: a blend of Chinese herbs and vitamins, combined into easy-to-swallow pills. The most critical aspect of this label is the statement that it is not certified by the United States Food and Drug Administration. This disclaimer is the manifestation of authoritative knowledge which serves to marginalize, if not discredit, herbal healing traditions, thereby perpetuating its “alternative” reputation.

-