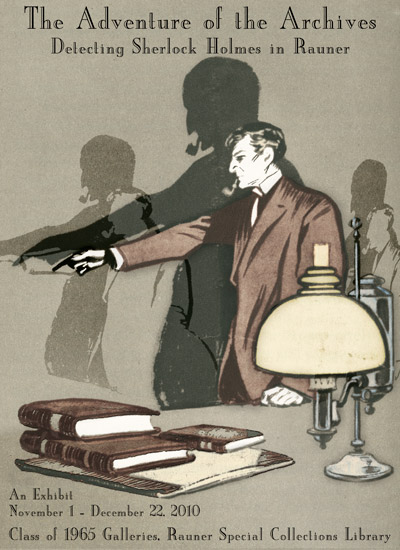

Adventure of the Archives: Detecting Sherlock Holmes in Rauner

The exhibition was curated by Laura Braunstein and was be on display in the Class of 1965 Galleries November 1 through December 22, 2010.

You may download a small, 8x10 version of the poster: Adventure_of_the_Archives.jpg (3.3 MB) You may also download a handlist of the items in this exhibition: Adventure of Archives.

Materials Included in the Exhibition

Case 1. In Which We First Meet Mr. Sherlock Holmes: First and Early Editions

Sherlock Holmes first appeared in A Study in Scarlet in 1887. Three years later, Arthur Conan Doyle wrote The Sign of the Four (later editions were retitled The Sign of Four). Both of these novellas were published in popular periodicals: Beeton’s Christmas Annual and Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine. Later stories were serialized, then published in one-volume editions that mimicked the design of the monthly magazine. The July 1891 issue of The Strand presented “A Scandal in Bohemia,” the first published story in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, with little fanfare.

The experience of reading a serialized novel is much like watching television drama: one installment per week, usually interrupted by advertising. Other literary and cultural experiences and the business of life also mark the intervals between serialized chapters. Serialized fiction happens in community, because other people are reading the same installments at the same time. This shared experience makes the stories fodder for conversation and a topic of ongoing literary criticism. When Conan Doyle finally published the collected edition of the early stories, it must have been like watching a favorite TV drama on DVD: readers could have as much as they wanted, all at once without interruptions.

- Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine. February 1890.

- The Strand. July-December 1891.

- Arthur Conan Doyle. A Study in Scarlet. London: Ward, Lock, Bowden & Co., 1891. Sine Illus H868stu

- Arthur Conan Doyle. The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. London: George Newnes, 1892. Rare Book PR4622 .A25 1892

- Arthur Conan Doyle. The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes. London: George Newnes, 1894. Rare Book PR4622 .M4 1894

- Arthur Conan Doyle. The Sign of Four. London: George Newnes, 1901. Sine Illus T68sig

- Arthur Conan Doyle. The Return of Sherlock Holmes. London: George Newnes, 1905. Rare Book PR4622 .R48 1905

- Arthur Conan Doyle. The Valley of Fear. London: Smith, Elder, 1915. Rare Book PR4622 .V35 1915

- Arthur Conan Doyle. His Last Bow: Some Reminiscences of Sherlock Holmes. London: J. Murray, 1917. Rare Book PR4622 .H5 1917

Case 2. Going to Hounds in Five Editions

Consider five different versions of The Hound of Baskervilles: the first installment in the original serialization in The Strand (1901); the 1902 first complete edition with illustrations by Sidney Paget; the screenplay for the 1938 film starring Basil Rathbone; an artist’s book from 1985 with photographs of Dartmoor by Michael Kenna; and a graphic novel published last year. Each of these incarnations offers profoundly different reading experiences. The suspense of serialization contrasts with the intense adventure of the collected edition. The emotional thrill of the movies and the eerie atmosphere evoked by photographs of the novella’s setting are transformed into the vivid colors of sequential art.

- The Strand. July-December 1901.

- Arthur Conan Doyle. The Hound of the Baskervilles: Another Adventure of Sherlock Holmes. London: G. Newnes, 1902. Rare Book PR4622 .H6 1902

- Ernest Pascal. “The Hound of the Baskervilles.” Screenplay, 1938. Scripts 1028

- Arthur Conan Doyle. The Later Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. Volume 2. New York: Limited Editions Club, 1952. Presses L629doya

- Arthur Conan Doyle. The Hound of the Baskervilles. Photographs by Michael Kenna. San Francisco: Arion Press, 1985. Presses A712do

- Ian Edington. The Hound of the Baskervilles. Illustrated by I. N. J. Culbard. New York: Sterling, 2009. Baker Berry PN6737.E34 H68 2009 [not available at Rauner]

Case 3. Acting a Part: Holmes on Stage

“The best way of successfully acting a part is to be it,” said Holmes.

“The Adventure of the Dying Detective”

The deerstalker cap, the bent briar pipe, “Elementary, my dear Watson” – all of these quintessential Holmesian elements were affectations cultivated by the American actor William Gillette. In 1899, Conan Doyle collaborated with Gillette on a stage version loosely adapted from several stories in the Adventures, but also including a love interest for Holmes. Panned by critics, the melodramatic play was enormously popular with audiences, and Gillette repeated his performance in touring productions and revivals for over thirty years. Gillette’s portrayal established such a powerful archetype that the American illustrator Frederic Dorr Steele modeled his 1903 illustrations for The Return of Sherlock Holmes on Gillette.

- Collier’s. September 1903.

- Sherlock Holmes. By William Gillette and Arthur Conan Doyle. Garrick Theatre, New York. December 1899. Program. Williams/Watson PR NY NYM-Garr 8991204

- Sherlock Holmes. By William Gillette and Arthur Conan Doyle. New Amsterdam Theatre, New York. December 1929. Program.

- Sherlock Holmes. By William Gillette and Arthur Conan Doyle. Broadhurst Theatre, New York. 1975. Program.

- Sherlock Holmes. By William Gillette and Arthur Conan Doyle. Souvenir program for farewell performances, 1929-30. Robinson Family papers (MS-1098), Box 18

Case 4. A Dartmouth Connection: Arthur Conan Doyle, Viljhalmur Stefansson, and Spiritualism

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle lost his son Kingsley during the 1918 influenza pandemic, two weeks before the Armistice that ended the First World War. Over the course of the war, Conan Doyle’s brother, two brothers-in-law, and nephew also died. In the wake of these losses, he became devoted to promoting spiritualism, which may have provided consolation in his grief, as it did to many who sought contact with departed loved ones. Many of Conan Doyle’s spiritualist writings omitted identifying him as the creator of Sherlock Holmes.

Among Rauner Library’s collections is the archive of the Arctic explorer Viljhalmur Stefansson, who taught at Dartmouth from 1947 to 1962. Stefansson first met Conan Doyle in London in 1913, and the two corresponded during Stefansson’s Arctic travels and through the First World War. Stefansson visited Conan Doyle in England in 1920, and wrote later in his autobiography that in terms of spiritualism, he found Conan Doyle’s “ready acceptance inconsistently naïve. Confronted with the spirit world, Doyle was more like Dr. Watson than Sherlock Holmes.”

Despite his friend’s skepticism, Conan Doyle enlisted Stefansson’s help in debunking a fraudulent séance during his 1922 American lecture tour. When Conan Doyle returned to England, he wrote to Stefansson that he felt his work in America had brought “knowledge and comfort to a lot of people.” He went on to write: “How strange our tasks! You are working on reindeer and I on disembodied spirits & both are equally part of the great whole. I quite see the Imperial aspect of your work.”

- Arthur Conan Doyle. The New Revelation. New York: George H. Doran, 1918. Rare Book BF1272 .D7 1918

- Arthur Conan Doyle. The Wanderings of a Spiritualist. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1921. Rare Book BF1283.D5 A3

- Arthur Conan Doyle to Viljhalmur Stefansson, 18 June [1922] Vilhjalmur Stefansson correspondence (MSS-196), Box 8, Folder 10.

- Telegram, Viljhalmur Stefansson to Arthur Conan Doyle, 29 March 1922. (MSS-196), Box 8, Folder 10.

- Telegram, Arthur Conan Doyle to Viljhalmur Stefansson, 30 March 1922. (MSS-196), Box 8, Folder 10.

- Transcript of séance. New York, 1922. (MSS-196), Box 8, Folder 10.

- Program for Lecture by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. New York, 1922.

- Viljhalmur Stefansson. Discovery: The Autobiography of Viljhalmur Stefansson. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964. Stefansson Alcove G635.s7 A 3 1964

G635.S7 A3 1964 - Arthur Conan Doyle. The Last Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. Being a New Edition of his “Memoirs.” London, G. Newnes, 1897. Rauner Brooke Library PR4622 .L3

- The English poet Rupert Brooke owned a copy of The Last Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – given to him in 1898, when he was eleven years old. Best known for his sonnet “The Soldier,” Brooke died of blood poisoning during the First World War.

A Note on the Type

The text for this exhibit was printed using Baskerville, a typeface designed in 1757 by John Baskerville of Birmingham, England, where Arthur Conan Doyle briefly lived.