Dartmouth College Library Bulletin

A Quintessential New Hampshire Policy:

The Seemingly Forgotten Mandatory

School Tax of 1789 to 1919

WALTER A. BACKOFEN

In 1789, the newly-formed State of New Hampshire took up the challenge of rebuilding its moribund public school system, A legacy of Massachusetts from 1647, when that was the seat of New Hampshire governance.[1] There was no shortage of evidence by this time for what to avoid in the future.Governor John Wentworth wasted no words in his address to the General Assembly in 1771: ‘Nine-tenths of your Towns are wholly without Schools, or have such vagrant foreign Masters as are much worse than none: Being for the most part unknown in their principles & deplorably illiterate.’[2] Jeremy Belknap, twelve years later, was convinced the situation had only gotten worse.[3] Finally, after six more years and the passage of a constitution that charged the state's citizenry ‘to cherish the interest of literature and the sciences,’[4] Wentworth's earlier call for ‘Legislative Care’ was answered: All that had gone before was repealed and a new law adopted on 18 June 1789, in the first wave of Federal-era legislation, which controlled mandatory school-tax policy until 1919.[5] Meanwhile, reform was under way in New Hampshire's mentor of 1647, and the legislature of Massachusetts produced its own law for the same purpose just one week later, after much rewriting and with much added to what had been on the books since 1647, but with nothing repealed.[6] After 142 years, the two states took philosophically different positions, with New Hampshire's arguably the more forward-looking. But today, after being out of sight for the eighty years since 1919, New Hampshire’s watershed law of 1789 is almost universally out of mind as well–which is surprising, if for no other reason than that questions of constitutional intent toward public education–to which this law does speak–have been high on the agendas of all branches of state government for the past few years.

How the tax policy of 1789 translated into practice was spelled out in a recent issue of the Library Bulletin, using for that purpose the extraordinary wealth of records in Special Collections from the town of Hanover, New Hampshire.[7] And from that exercise it was clear that as wisely as New Hampshire acted in 1789, the result was basically a rearrangement of old ideas.

For in its restructured mode the state simply called on the same tax formula for school support that had been in use for paying the bills of the province since no later than 1693, and would continue serving the state that way until the tobacco tax took over in 1939.[8] The proportionate taxation of private property was to remain

The uniqueness lay in the power reserved by the General Court to decide, in its wisdom, how much money would have to be raised annually as a collective effort by the towns of the state to meet the threshold needs of their schools. Once into the nineteenth century, those sums were announced as multiples of $1000.00, which has invited making M the multiple in the following discussion and M ¥ 1000 the total amount called for by the legislature as the annual outlay. Under the proportionate rule, each town's share of this total was automatically the same as its share of the state's entire taxable valuation, and whatever that sum was for any particular town would have to be spent at home on the operation of that town’s own schools (chiefly for teachers’ salaries with very little al-lowed for the building and repair of schoolhouses). Two outcomes of the plan were inevitable: One in the realm of concept that was inherent to its design, the other a concession to the tactical challenge of implementing it.

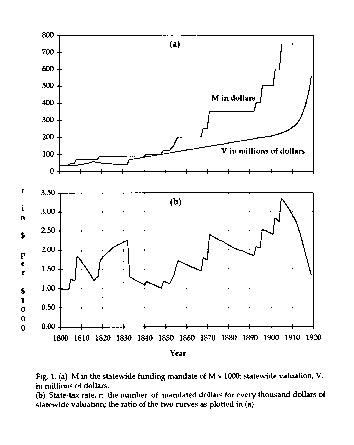

The first and perhaps more foreseeable outcome follows from noting, through the history of M in Figure 1a, how the General Court's decrees were increased over the years.[9] An accelerated growth on balance, the irregular step-by-step advances and the late-century upsurge say much about the history of the state's concern over a variety of socioeconomic issues affecting its children. In this context, the state-tax rate was entirely derivative, and would be unknown until the valuation-base on which the stepwise tax levy was made had been es-tablished. In fact, ‘rate’ was never a part of the school-tax vocabulary until 1899 when the local tax rate became a factor in eligibility for the state's first-ever equalized aid to deserving towns.[10] Yet, the definition of the rate that received no mention for over a century clarifies more than anything the specialness of the New Hampshire school-tax strategy. And this requires the annual statewide valuation, or V, hereafter, as the symbol for whatever sum that was. A minor investigation in its own right, the present exercise is well enough served by the slightly smoothed but defensible record of V, in millions of raw dollars of the day, entered in Figure 1a, as well.[11] Less than 40 million dollars in 1800, V was more than fifteen times as large by 1919, with over half of that growth in the last twenty years; after a false start and a statewide revaluation in 1833, its upward course was never seriously interrupted.

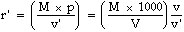

With M ¥ 1000 the sum to be raised from base V , the de facto state-tax rate, r , would be the ratio of the two, or

![]()

which appears in Figure 1b as the number of tax dollars per $1000.00 of base V. (Treating V as a multiplier like M in Figure 1a, to get both on the same scale, makes r in Figure 1b the ratio of the two curves just as they are plotted in Figure 1a). Totally dependent on the M and V that defined it, r was driven along a course in Fig. 1b that looks as much as anything like a dorsal fin heading upscale, with spines located precisely where the General Court made its decisions to increase M. Each time that happened (except in 1819), the rate had been falling because the fixed M ¥ 1000 was being supplied from a rising V. Therefore, as the next step up in M was taken, the decline was reversed momentarily and a spine in r created. Only once did the reversal last more than a year, and that was because of four successive increases in the spending mandate, from 1853 to 1856, during a major episode in the sporadically ongoing process of reform. At the opposite extreme, for two periods of twenty-two years each–1819-1841 and 1871-1893–the M ¥ 1000 mandates went unchanged.

The other outcome of the New Hampshire school-tax plan--an implementation problem–becomes evident just as soon as this implicitly common rate, r, in Figure 1b is applied each year to every individual town's tax base. Letting v be the dollar value of that base, the annual school tax by town would, in principle, be r ¥ v, into which the above definition of r can be inserted to produce

![]()

where

![]()

In isolation like this, p is what was once called the ‘proportion of public taxes.’ Virtually unique to each town, it was pivotal for more than two centuries to all such tax computations (although never identified symbolically as it is here).[12] Technically, p was the town's mandatory contribution to every $1000 of whatever aggregate tax was to be raised by the state, with the actual dollars and cents value of p determined by the town's share of the state's total valuation, or v/V. In just these terms, however, p can't help seeming redundant. For a proportionate tax could have been calculated without going beyond the v and V, by themselves, that went into the definition of p. But as a practical matter, there was no way of becoming informed about V before all v were first reported. And although a value for v was owed to the state each year, combining all of them to work out a new tax rate every time was simply not feasible. To resolve the impasse, what looks like another de facto decision was made early in the history of the province tax to satisfy the underlying requirement–proportionate taxes at uniform rates–if not every year, at least once every five, using a value for p that would be determined anew and published for each town on that schedule.[13] Presumably, enough time was allowed this way for collecting, compiling, and confirming the multitude of data that would, ultimately, lead to all towns being ranked proportionately, by p, in one of those years. And from that ranking, after 1789, could be taken an M ¥ p for each town (with M following an independent schedule set by the Legislature) that would be good ‘for the time being’ in the words of the law–sometimes for no more than a year–after which it might change ‘for a greater or lesser sum.’ The tax process became more or less manageable as a result, and gained a small measure of stability.

Yet under cover of that temporary stability in M ¥ p there could still be change. In particular, the local annual mandatory school-tax rate handed down by the selectmen in any town of assigned M ¥ p (call this rate r' to distinguish it from the common r in Figure 1b that the State can be imagined to have had in mind) would always be calculated on the basis of that year's local valuation, v’, as

![]()

and levied accordingly. After substituting for p , however, and recalling the def-inition of r,

![]()

![]()

![]()

which shows that if the v' discovered in the reappraisal of each spring differed from v (accurate only at apportionment time), v/v’ would be greater or less than one, to make it unlikely that the r' presented to the taxpayer of this particular town would still be the same as that faced by the taxpayers of every other town. Only for the special case of v changing exactly in proportion to V would the local rate continue to be that for the state as a whole.[14] Thus the principle of uniform state-tax rates was always at risk as a concession to preserving State control over the aggregate tax.

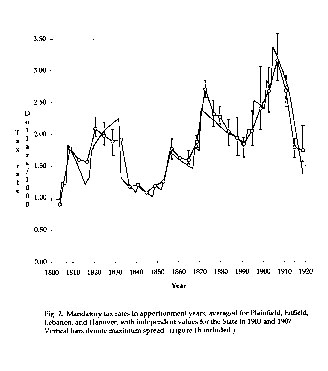

To model how the decision of 1789 played out in the end, the rate line in Fig. 1b can be imagined as pinned in place just at apportionment time, when every town's p was newly assigned and, in theory, all tax rates should have been the same. From one pin to the next, however, each town's line could bow: Upward if the town became poorer, or downward if it grew richer, with how much, either way, influenced by all the details of the actual wealth redistribution scenario. Evidence of how closely practice and theory came together is found in Figure 2, where mandatory tax rates for a few Upper Valley towns with accessible records of year-by-year valuation have been averaged together in apportionment years and overlaid on the basic rate line.[15] Given the uncertainties, especially in V, the agreement in these terms is close enough to be taken as an endorsement of the underlying argument. Yet there was spread among the rates in the different samples, over ranges indicated by the vertical extensions through the affected data points. This necessarily raises a question about how far the concession to tax-rate disparities might really have gone as this inherently cumber-some plan faced up to more or less rapid change, notably of the kind that arrived with the end of the century.

The state's accelerating accumulation of wealth necessarily kept pressure on the mandatory school-tax rate to decline; as V grew larger in the first equation, under an unchanging M ¥ 1000, the rate, r, had to go down. Taxpayers as a whole were understandably supportive of a trend that rewarded fiscal growth with a falling tax rate, although schoolchildren as a class were badly served by the result. Under a tax rate shrinking uniformly across the state, any town not growing as fast as the state would find the mandated part of its school budget shrinking, too, and more rapidly still if its tax base actually decreased. Meanwhile, the problem only intensified as the state’s rising taxable wealth became more stratified among its towns.[16] By 1900 half the taxable wealth of the state, or half of the mandatory statewide school budget, belonged to just ten of its towns (about 4 percent of the total, down from 25 percent in 1820). Half the state's people, however, could not then be contained in fewer than twenty of its most populous towns. On balance, therefore, the wealthier towns were also experiencing a greater concentration of assets among their school-age children. The plight of the poorer towns, particularly after 1840, showed up in disproportionate amounts of tax voluntarism, as self-imposed school taxes lifted actual payments increasingly higher than the mandated levels.[17] The only control available to the state for raising the support threshold for property-poor towns was to raise it for everyone, needful or not, which accounts for the greatly accelerated growth in M in Figure 1a after 1890.

A remedy came, finally, in 1919, as part of the next watershed education-reform act.[18] At that point the school-tax rate was first brought under direct control, as Vermont's had been in 1810, and which New Hampshire was unlikely to have missed as it looked to Vermont for guidance in dealing with its now seriously malfunctioning school system.[19] Where New Hampshire set the floor in 1919, at $3.50/1000, was virtually the peak from the last 130 years fleetingly reached around 1905, before the plunge to barely half that level by 1919 and a return to the tax rate of roughly fifty years earlier. From 1919 on, however, a town could not lose support in school-tax dollars without first losing assets; just growing too slowly was no longer reason enough. Recovering like a phoenix, in only one year the mandatory tax rate would rise by over 100 percent, never to fall again. As a singular event in the life of the New Hampshire school-tax payer up to that point, no other may have compared in trauma with the experience of entering 1919 after 130 years in 1789. The reasons for all of those years of laboriously adjusting a formula that always tested the envelope of proportional taxation, while rewarding growth with a lower tax rate, may never have seemed clearer to the taxpayer than at that moment. Schoolchildren, on the other hand, might have breathed a collective sigh of relief.

[1] Massachusetts, Records of the Governor and Company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England. Printed by order of the legislature, 5 vols., ed. Nathaniel B. Shurtleff (Boston: W. White,1853-1854), 2:203.

[2] New Hampshire, [Provincial and State Papers], 40 vols. (Concord, N.H., 1867-1943), 7:287.

[3] ‘[The Belknap Papers],’ in Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 5th ser. (1877), 2:287-288.

[4] New Hampshire Constitution (1784), art. 83.

[5] New Hampshire, Laws, Statutes, etc., Laws of New Hampshire: Including Public and Private Acts and Resolves and the Royal Commissions and Instructions, with Historical and Descriptive Notes, and an Appendix, ed. Albert Stillman Batchellor, 10 vols. (Manchester, N.H.: J. B. Clarke, 1904-1922), vol. 5, First Constitutional Period 1784-1792, 449.

[6] Massachusetts, Laws, Statutes, etc., The General Laws of Massachusetts, from the Adoption of the Constitution to February, 1822, with the Constitutions of the United States and of this Commonwealth, together with Their Respective Amendments, Prefixed, 2 vols. (Boston: Wells & Lilly and Cummings & Hilliard, 1823-1832), 1:367.

[7] Walter A. Backofen, ‘The Town of Hanover as a Window on Public-School Funding in the State of New Hampshire: 1789-1919,’ Dartmouth College Library Bulletin, n.s., 39:1 (November 1998), 26-43.

[8] For more discussion, see Walter A. Backofen, ‘New Hampshire’s Proportion of Public Taxes: Its Role in Public School Funding: 1789-1919,’ Dartmouth College Library Bulletin, n.s., 34:1 (November 1993), 17.

[9] Backofen, ‘New Hampshire’s Proportion,’ 17.

[10] New Hampshire, Laws, Statutes, etc., Laws of the State of New Hampshire (1899), 318. For more discussion, see Walter A. Backofen, New Hampshire’s Public School system: 1789-1919: The Taxpayer-Oriented Years (E. Plainfield, N.H.: Lord Timothy Dexter Press, 1994). There is a copy in Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections.

[11] Backofen, New Hampshire’s Public School System, 16-21.

[12] Backofen, ‘New Hampshire’s Proportion.’

[13] Backofen, ‘New Hampshire’s Proportion.’

[14] Let the state-tax rate between reapportionments be

where V' is the corresponding instantaneous valuation. At the town level,

where v and V apply at apportionment time. For the two rates to be identical,

[15] Backofen, New Hampshire’s Public School System.

[16] Walter A. Backofen, New Hampshire’s Education Reform Act of 1789 and the Next One Hundred and Thirty Years, 15 March 1998. There is a copy in Dartmouth College Library, Special Collections.

[17] Backofen, New Hampshire’s Education Reform Act.[18] ‘An Act in Amendment of the laws Relating to the Public Schools and Establishing a State Board of Education,’ New Hampshire, Laws, Statutes, etc., Laws of the State of New Hampshire (1919), 155-166.

[19] John Charles Huden, Development of State School Administration in Vermont ([Montpelier, Vt.:] Vermont Historical Society, 1943), 108.