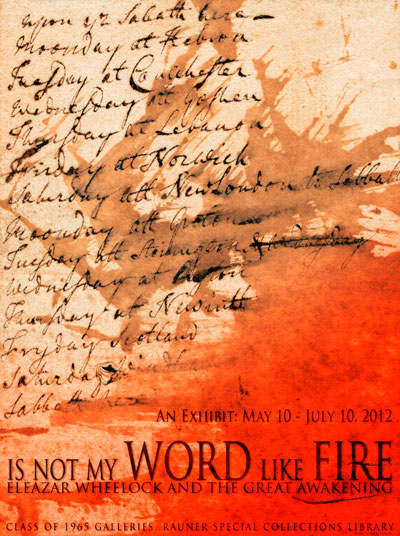

Is Not My Word Like Fire? Eleazar Wheelock and the Great Awakening

The Great Awakening, a religious revival that began around 1741, enflamed church and civil life in New England. The revival's vision of personal piety and salvation challenged the delicate balance of Puritan life. It was seen by some as a remarkable work of God's Spirit; by others, an extreme threat to public order.

One key participant was a young evangelist and preacher who was a friend of Jonathan Edwards and pastor of the church at Lebanon Crank, Connecticut: Eleazar Wheelock. Wheelock's experience of the Great Awakening reveals its themes, its tensions, and the divisions it produced in New England. His story offers a glimpse into the revival that still colors political and religious visions today. And it was his personal experience as "a voice crying in the wilderness" that led to the establishment of Dartmouth College.

The exhibition was curated by Eliz Kirk, Associate Librarian for Information Resources, and was on display in the Class of 1965 Galleries from May 10 to July 30, 2012.

You may download a small, 8x10 version of the poster: GreatAwakening.jpg You may also download a handlist of the items in this exhibition: LikeFire.

Materials Included in the Exhibition

Case 1.

- Increase Mather. The First Principles of New-England Concerning the Subject of Baptisme & Communion of Churches. Cambridge: Printed by Samuel Green, 1675. Rare Book BX7136 .M37 1675

- This pamphlet describes the Half-Way Covenant, which regulated the church structure in Puritan New England when the Great Awakening began. The Covenant held that baptized members of churches who had not made any individual profession of faith could have their children baptized into the local church, but could not take part in the sacrament or practice of communion, which was reserved for those who had professed faith. The established churches saw the Half-Way Covenant as a way to keep people within the church’s sphere of influence and discipline. Others saw it as evidence that the church was in a state of spiritual decay.

- Jonathan Edwards. A Faithful Narrative of the Surprizing Work of God, in the Conversion of Many Hundred Souls in Northampton. London: John Oswald, 1737. Rare Book BR520 .E55 1737

- Jonathan Edwards was the catalyst of the Great Awakening and this text describes its antecedents. It mentions revivals in churches throughout southern New England, including in Lebanon Crank, Connecticut, “where the Reverend Mr. Wheelock, a young gentleman, is lately settled.”

- Jonathan Edwards. Letter to Eleazar Wheelock. June 9, 1741. Eleazar Wheelock Collection (MS-1310), Folder 741359

- Edwards’s father, Timothy Edwards, was minister at Scantic (Stoughton), Massachusetts, where he had a difficult relationship with his congregation. In this letter, Edwards appeals to two well-known revivalists to go and preach at Scantic: Eleazar Wheelock and his brother-in-law, Benjamin Pomeroy.

- George Whitefield. A Continuation of the Reverend Mr. Whitefield’s Journal from his Embarking After the Embargo to his Arrival at Savannah in Georgia. 2nd ed. [London]: 1740. Rare Book BX 9225 .W4 A3 1738

- George Whitefield became known as the Great Itinerant for his successive preaching tours of the colonies and across Great Britain. His impassioned and often dramatic revivalist preaching had a tremendous impact on the Great Awakening. It is estimated that Whitefield preached to 10,000,000 people over the course of his 18,000 sermon career (definitely the Billy Graham of his day). As noted here, he spoke to assemblies of thousands.

- Eleazar Wheelock. Letter to Stephen Williams. May 22, 1740. Eleazar Wheelock Collection (MS-1310), Folder 740322

- Wheelock describes a visit to New York, where he met George Whitefield and heard him preach. He tells his friend Williams that he doesn’t hear anything unusual in Whitefield’s preaching other than the “length of his sermon and the fervor and vehemence with which he delivered it….”

Case 2.

- The Testimony and Advice of an Assembly of Pastors of Churches in New-England, at a Meeting in Boston, July 7, 1743. Occasion’d by the Late Happy Revival of Religion. Boston: Printed by S. Kneeland, T. Green, and N. Proctor, 1743. Alumni B81te

- The Great Awakening aroused as much antipathy as it did revival. This pamphlet, which advocated the revival, includes a testimony by Wheelock and a number of other ministers on revivals of spiritual vitality in their churches.

- Eleazar Wheelock. Letter to Sarah Wheelock. June 28, 1742.

- Wheelock was much in demand as an itinerant revivalist, as he wrote to his wife: “The week before last I preachd 10 sermons… Last week I preachd 10 times again… I am exceedingly worn out with constant labour and much watching."

- The Testimony of the Pastors of the Churches in the Province of Massachusetts-Bay in New-England, at Their Annual Convention in Boston, May 25, 1743. Against Several Errors in Doctrine, and Disorders in Practice, Which Have Late Obtained in Various Parts of the Land. Boston: Printed by Rogers and Fowle, 1743. Rare Book BX7230 .C66 1743

- An anti-Awakening pamphlet questions the motives of the revivalists. Especially worrisome to the authors are the sermons against the Half-Way Covenant and the criticism against established ministers who back it. This challenge to established order earned revivalists the designation of antinomians.

- Solomon Williams. Letter to Eleazar Wheelock. July 17, 1741. Eleazar Wheelock Collection (MS-1310), Folder 741417

- Williams reports that James Davenport (Wheelock’s brother-in-law) has been preaching in New London, Connecticut against the local minister. Davenport was one of the most startling figures of the Awakening—highly emotional, highly dramatic, subject to rages, collapses, and depression. He advocated Separatism, urging his listeners to leave established churches that he believed had drifted from their original purpose.

- William Hobby. An Inquiry into the Itinerancy, and the Conduct of the Rev. Mr. George Whitefield, an Itinerant Preacher: Vindicating the Former Against the Charge of Unlawfulness and Inexpediency, and the Latter Against Some Aspersions, Which Have Frequently Been Cast Upon Him. Boston: Printed by Rogers and Fowle, 1745. Rare Book BX9225.W4 H36 1745

- Itinerant preaching had always been discouraged in Puritan New England. As Increase Mather wrote on 1700, “To say that a Wandering Levite who has no Flock is a Pastor, is as good sense as to say, that he who has no Children is a Father. (The Order of the Gospel)” This pamphlet seeks to exonerate Whitefield’s reputation. Some pamphleteers and ministers blamed the revivalists as a group for the excesses of those who, like Davenport, did much damage to local churches."

- Eleazar Wheelock. Sermon notes. no date. One of the sermons from Eleazar Wheelock sermons (MS-940)

- This two-week preaching schedule scrawled on the back of some sermon notes shows Wheelock’s popularity as an evangelist. “Upon the Sabbath here, Monday at Hebron, Tuesday at Colchester, Wednesday at Goshen….“

- The State of Religion in New-England, Since the Reverend Mr. George Whitefield’s Arrival There. In a Letter from a Gentleman in New-England to his Friend in Glasgow. Glasgow: Printed by R. Foulis, 1742. Rare Book BR520 .S83 1742

- The author describes the difficult impact on local churches and their ministers from preaching by itinerant Exhorters (lay preachers). The Great Awakening signaled the ascendancy of the lay evangelist and a shift from very structured preaching to more emotional appeal. These changes were not gradual, easy, or universally accepted.

- Eleazar Wheelock. Letter to Thomas Clap. 1742. Eleazar Wheelock Collection (MS-1310), Folder 742900.1

- Connecticut had the strictest state-church bonds of the New England colonies. A law known as the Act for Regulating Abuses and Correcting Disorders in Ecclesiastical Affairs (1742) withheld a minister’s salary if he preached in another parish without the express invitation of the parish’s minister, a strong measure meant to bring itinerant revivalism to a full stop. Here, Wheelock notes to his childhood pastor, now the president of Yale, that he has been deprived of his salary, causing his family distress and suffering.

- Charles Chauncy. Seasonable Thoughts on the State of Religion in New-England, a Treatise in Five Parts, with a Preface Giving an Account of the Antinomians, Familists, and Libertines, who Infected these Churches. Boston: Printed by Rogers and Fowle for Samuel Eliot in Cornhill, 1743. Rare Book BR520 .C45 1743

- Chauncy, pastor the First Church in Boston, was the anti-revivalists’ principal speaker and pamphleteer. He decries Whitefield’s itinerancy and Davenport’s excesses and then condemns their fellow revivalists by association, including Wheelock.

- Eleazar Wheelock. Letter to Samuel Whitman. December 27, 1741. Eleazar Wheelock Collection (MS-1310), Folder 741677

- Unlike his brother-in-law, James Davenport, Wheelock was not a Separatist, regardless of the accusations of Chauncy and some others. He reacts strongly to one accuser: “And why Honored Sir did you hate me thus to suffer sin upon me and how you will excuse yourself from a very gross violation of our Savior’s rule, Matt. 28, 15, 16, I can’t tell. It is a rule I teach my people to observe… and have disciplined them for the breach of it.…”

Case 3.

- Eleazar Wheelock. Letter to Stephen Williams. February 18, 1744. Eleazar Wheelock Collection (MS-1310), Folder 745168

- Too radical for those like Chauncy, Wheelock was clearly too Establishment for the radicals. He reports to Williams on a recent preaching visit to Windham, where the Separatists would not come to hear him.

- Jonathan Edwards. Some Thoughts Concerning the Present Revival of Religion in New-England, and the Way in Which it Ought to be Acknowledged and Promoted… Edinburgh: Reprinted by T. Lumisden and J. Robertson, 1743. Rare Book BR520 .E5 1743

- Edwards sparked the Great Awakening with A Faithful Narrative. Here, as the fervor begins to wane, he reflects on its aims as well as acknowledging the excesses that split churches, hoping to bring closure to the ongoing debate. Part One of this work chronicles the revival’s history. Here, in Part Two, he tells his readers that the preaching of salvation—the goal of the Great Awakening—is the central tenet of the Church.

- Solomon Williams and Eleazar Wheelock. Two Letters from the Reverend Mr. Williams & Wheelock of Lebanon, to the Rev. Mr. Davenport, which were the Principal Means of his Late Conviction and Retraction. With a Letter from Mr. Davenport, Desiring their Publication, for the Good of Others… Boston: Kneeland and Green, 1744. Alumni W57wt

- After a few years of what even his friends deemed reckless accusations against established ministers and a long history of emotional extremes, James Davenport wanted to return to the community of clergy. In preparation, this pamphlet was published to demonstrate that he was being corrected by colleagues in good standing. Wheelock’s letter defends the practice of commissioning and ordaining ministers against the undisciplined preaching of lay Exhorters: “It is the Will of Christ that his People should hear all those whom he sends to preach his Gospel… But it is not his Will that those should be heard as his Embassadors whom he does not send.”

- Eleazar Wheelock. Letter to Ebeneezer Pemberton. October 24, 1759. Eleazar Wheelock Collection (MS-1310), Folder 759574

- There is no record of Wheelock defending himself against Charles Chauncy’s accusations until 1759, fourteen years after the publication of Seasonable Thoughts. The lingering gossip, the strained relationships, and ongoing ill will in New England may be clearly inferred in this letter to another minister. So too the reader may wonder about Wheelock’s own sense of his legacy at this point in his life. “And so I have been advised by gentlemen of good and publick characters in your government, that my name and religion with it have and do suffer very much, and are in danger of suffering more in succeeding generations…. “

- Eleazar Wheelock. The Preaching of Christ an Expression of God’s Great Love to Sinners, and Therefore a Great Savour to Him. Boston: Printed by S. Kneeland, 1761. Alumni W57pc

- Wheelock had left itinerant preaching behind and turned to his Latin School and the establishment of Moor’s Indian Charity School well before the publication of this sermon. Preaching in 1760 on the occasion of Benjamin Trumbull’s ordination, Wheelock is clear that his views on the primary goal of preaching have not changed: “That Christ is then truly preached, when the Preaching is most suitable to answer the great Ends of it. Which are, that Sinners may know him; and be persuaded of his great Salvation.”