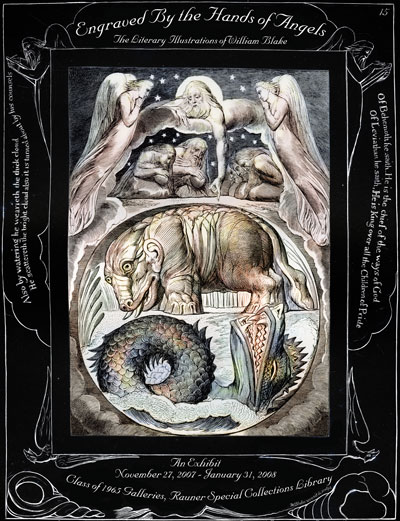

Engraved by the Hands of Angels: The Literary Illustrations of William Blake

Celebrate the 250th birthday of William Blake, poet, painter, printer, and visionary, with an exhibition of his literary illustrations. On view are a proof-set of his Illustrations of the Book of Job, plates from a stunning full-color facsimile of the Paradise Lost watercolors, the masterpiece engraving Chaucer's Canterbury Pilgrims, a selection of books demonstrating Blake's career as a commercial illustrator, and other items from the Library's extensive collection of Blake materials. In addition, four engravings in the Hood Museum of Art's collections from Blake's series illustrating Dante's Inferno (not published until after his death) are on display at the Hood Museum through January 13.

Celebrate the 250th birthday of William Blake, poet, painter, printer, and visionary, with an exhibition of his literary illustrations. On view are a proof-set of his Illustrations of the Book of Job, plates from a stunning full-color facsimile of the Paradise Lost watercolors, the masterpiece engraving Chaucer's Canterbury Pilgrims, a selection of books demonstrating Blake's career as a commercial illustrator, and other items from the Library's extensive collection of Blake materials. In addition, four engravings in the Hood Museum of Art's collections from Blake's series illustrating Dante's Inferno (not published until after his death) are on display at the Hood Museum through January 13.

"It is certain that the pictures deserve to be engraved by the hands of angels..." -- William Blake, letter to William Hayley, 22 June 1804.

The exhibition was curated by Laura Braunstein and was on display in the Class of 1965 Galleries from November 27, 2007 to January 31, 2008.

You may download a small, 8x10 version of the poster: HandsOfAngels.jpg (2.4 MB) You may also download a handlist of the items in this exhibition: HandsOfAngels.

Materials Included in the Exhibition

Case 1.

William Blake has an unassailably popular reputation today, and many readers consider him to be a mad yet beloved genius. In his lifetime, however, he was continually frustrated in his attempts to be recognized as a serious artist. His own books, exquisite blends of words and images, failed to reach a large audience. As a result, he relied on commissions, as illustrating other authors’ works was an important source of income.

As Blake wrote in Jerusalem (1804-20), “I must Create a System or be enslav’d by another Man’s.” This desire for grand narratives may have drawn Blake to epic poetry. Blake’s epic illustrations go beyond simple illumination to provide original interpretations. John Milton figured for Blake as a prophet, and inspired Blake’s own epic, Milton (written 1804-1810). In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1793), Blake wrote that Milton was “of the Devils Party without knowing it.” His watercolor illustrations for Milton’s Paradise Lost (1807-08) clearly foreground Satan as the epic’s hero.

Dante’s Inferno and the Book of Job may seem unlikely subjects for Blake, whose philosophy rebelled at the idea of a divine system of eternal punishment. The Dante and Job series were both commissioned late in Blake’s life by John Linnell, a younger artist who introduced Blake to his circle. These last works express deep ambivalence toward the moral universe of their subjects. Blake’s illustrations offer sympathy toward individuals suffering beneath a scheme that figures their resistance as sin.

- William Blake. Illustrations of the Book of Job. London: William Blake, 1825. Val 825 B58 R7

- Selections from the text of the Book of Job frame Blake’s line engravings and provide a commentary that is more consistent with his own philosophy. In the first plate of the book, Blake includes the epigraph “the Letter killeth/ the Spirit giveth Life/ It is Spiritually Discerned” (a gloss of 2 Corinthians 3:5-7). For Blake, as for Job, living by an externally imposed system destroys true spiritual awareness.

- William Blake. Thirteen Watercolor Drawings by William Blake Illustrating Paradise Lost by John Milton. San Francisco: Arion Press, 2004. Facsimile of the original paintings in the Huntington Library’s collection. Presses A712bla

- In this scene, from Book 2 of Paradise Lost, Satan comes to the Gates of Hell and confronts his daughter Sin, who “seem’d Woman to the waste, and fair,/ But ended foul in many a scaly fould” (650-51). Their son, Death (the product of an incestuous union), is introduced to the poem on line 666, as “the other shape,/ If shape it might be called that shape had none” (666-67).

- Robert Blair. The Grave, a Poem. Illustrated by Twelve Etchings Executed from the Original Designs. London: T. Bensley, 1808. Val 825 B57 R31

- Robert Blair’s poem The Grave was already popular when Blake was commissioned in 1808 to illustrate a new deluxe edition. Blake’s patron Robert Cromek was allegedly so disturbed by Blake’s designs that he hired Louis Schiavonetti, a more commercially successful artist, to engrave them.

- Hofer, Philip. An Illustration by William Blake for the ‘Circle of the Traitors’: Dante’s Inferno, Canto XXXII. Meriden, CT: Meriden Gravure Company, 1954. Presses S859bℓ

- In this scene from Inferno, Canto XXXII, lines 68-120, Dante and Virgil walk across a frozen lake at the bottom of Hell, in which traitors are embedded in ice from the neck down. Dante trips over the head of one of the traitors, who cries out, compelling Dante to engage him in conversation. Four prints from Blake’s Inferno series are on view at the Hood Museum through January 13, 2008.

Case 2.

In 1806, Blake’s sometime-patron, Robert Cromek, commissioned the artist Thomas Stothard to produce a painting on the subject of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. They planned to make an engraving of this painting and sell copies by subscription. Blake had been expecting the commission, and later claimed that Cromek and Stothard had betrayed him by stealing his original idea. Blake decided to paint the subject himself, and engrave and print copies in his own studio. The work was first exhibited in Blake’s brother’s hosiery shop in 1809.

Unlike many of Blake’s other literary illustrations, which envision individual episodes from longer narratives, Chaucer’s Canterbury Pilgrims encompasses Geoffrey Chaucer’s entire work in one epic tableau. Blake saw Chaucer’s characters as timeless archetypes, “the physiognomies or lineaments of universal human life,” as he wrote in the catalogue/manifesto that accompanied the original exhibition. Yet what strikes the viewer about Blake’s pilgrims is their essential uniqueness, their humanness.

- William Blake. Chaucer’s Canterbury Pilgrims. [between 1810 and 1881] Iconography 1596

- Geoffrey Chaucer. The Prologue to the Tales of Caunterbury. Ashendene, Hertfordshire: The Ashendene Press, 1897. Presses A819cha

- The illustrations in this small-press edition of the Prologue are reproductions of woodcuts in William Caxton’s 1478 publication of The Canterbury Tales. The figures are almost so generic as to be interchangeable.

- Geoffrey Chaucer. The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, Now Newly Imprinted. Hammersmith, Middlesex: The Kelmscott Press, 1896. Presses K299c

- Known as the “Kelmscott Chaucer,” William Morris’s exquisite production began a new chapter in the history of the book. The wood-engraved illustrations by Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones hearken back to Medieval illuminations in their idealization of a lost chivalric realm.

- Geoffrey Chaucer. The Canterbury Tales of Geoffrey Chaucer, Together with a Version in Modern English Verse by William Van Wyck, Illustrated by Rockwell Kent. New York: Covici-Friede, 1930. Illus K418c

- Rockwell Kent’s pilgrims, produced by offset lithography for this limited edition, are true individuals. In this sense, Kent may be the twentieth-century illustrator who comes closest to inheriting Blake’s vision of the life and beauty of Chaucer’s characters.

Case 3.

Many of the characteristics that shaped Blake’s uniqueness as a poet and visual artist can be traced to his career as a printer and engraver. Radical politics and the dissenting Church were the culture of his profession. Many urban craftsmen rejected elite institutions despite their dependence on powerful patrons for their livelihoods. Patrons who commissioned Blake to engrave other artists’ designs were often indifferent to his own desires and beliefs. A professional commitment to his craft often conflicts with an underlying radical message.

- John Stedman. Narrative of Five Years’ Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, in Guiana, on the Wild Coast of South America, from the Year 1772 to 1777. London: J. Johnson, 1796. [Vol. 1] Roberts Library F2410 .S815 or Rare Book F2410 .S815 c.2

- John Stedman. Narrative of Five Years’ Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, in Guiana, on the Wild Coast of South America, from the Year 1772 to 1777. London: J. Johnson, 1796. [Vol. 2]

- Stedman’s Narrative was an important text of the nascent British anti-slavery movement. Blake demonstrates sympathy for the suffering of a tortured female slave by lending her figure some modesty with an almost classical draping. This figure seems to reappear in the final plate of Stedman’s second volume. The emblematic tableau represents Europe as a white woman, gazing chastely downward, supported by the brazen female figures of Africa and America. This image undercuts the radical message of earlier plates by reinscribing the racial and sexual dynamics of empire.

- The Cabinet of the Arts: A Series of Engravings by English Artists. London: 1799. Rare Book NE631 .C3

- This plate, questionably attributed to Blake, illustrates a Royalist account of the early events of the French Revolution, written in French and published in English in 1792. Blake’s engraving of Marie Antoinette, seeking safety from the mob in the arms of Louis XVI, looks entirely conventional in the context of late-eighteenth-century book illustration.

- Robert Thornton. The Pastorals of Virgil, with a Course of English Reading, Adapted for Schools. London: J. McGowan, 1821. Illus B581vip

- Blake’s wood engravings caused some controversy among the other artists commissioned to illustrate this textbook edition of Virgil. At the time it was customary to excavate the woodblock around the outline of an image, producing positive black lines in a white background, which simulated the effect of copper engraving. Blake, conversely, carved his images directly on the block, creating positive white lines in a black background. These tiny landscapes are startling in their dark, evocative beauty.

- Erasmus Darwin. The Botanic Garden. Part I. Containing the Economy of Vegetation. A Poem. With Philosophical Notes. London: J. Johnson, 1791. Fields 17

- John Milton. Poems in English with Illustrations by William Blake. London: Nonesuch, 1926. Presses N731mi

- Darwin’s long poem was a bestselling work that popularized natural history. Henry Fuseli, a friend and supporter of Blake, was commissioned to illustrate the first volume, with Blake as engraver. This plate pictures the cyclical flooding of the Nile as personified by the dog-god Anubis fertilizing the land. The storm god of Fuseli’s design reappears as the figure of “triumphant Death” in Blake’s illustration of the Lazar House in Paradise Lost (Book 11, lines 477-93), and in Fuseli’s 1793 painting of the same subject.

- Henry Fuseli. The Vision of the Lazar House. Kunsthaus Zürich. Fuseli: The Wild Swiss. By Franziska Lentzsch. Zürich: Scheidegger & Spiess, 2005. Cat. 186. Sherman ND853.F85 F98 2005 [not in Rauner]