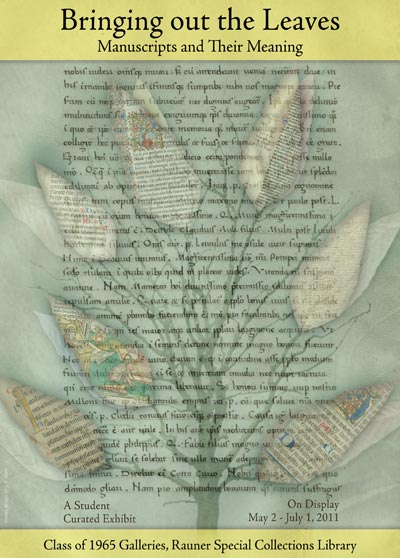

Bringing out the Leaves: Manuscripts and their Meaning

Dartmouth has a rich and diverse collection of medieval manuscripts that are used to support teaching and learning at the College. This exhibit represents the exploration of eight undergraduate students who share a fascination with the Middle Ages. The brought their own interests to the materials, sometimes selecting the same items for quite different purposes. The ensuing negotiation illustrated well how meaning depends greatly on point of view and context. We invite you to carry on the exploration by seeking you own connections among these intriguing materials!

Dartmouth has a rich and diverse collection of medieval manuscripts that are used to support teaching and learning at the College. This exhibit represents the exploration of eight undergraduate students who share a fascination with the Middle Ages. The brought their own interests to the materials, sometimes selecting the same items for quite different purposes. The ensuing negotiation illustrated well how meaning depends greatly on point of view and context. We invite you to carry on the exploration by seeking you own connections among these intriguing materials!

Curated by

- John M. Burden ’11

- Benjamin A. Groveman ‘12

- Lia D. Grigg ‘11

- Kevin L. Mallen ’11

- Olivia Leigh M. Martin ’13

- Bridgette T. Taylor ‘13

- Madeline L. Sims ’12

- Emily J. Ulrich ‘11

- Professor Michelle Warren

The exhibit will be on display in Rauner Library's Class of 1965 Galleries from May 2 to July 1, 2011.

You may download a small, 8x10 version of the poster: BringingOutTheLeaves.jpg (2.1 MB) You may also download a handlist of the items in this exhibition: Bringing out the Leaves.Materials Included in the Exhibition

Case 1. In the Margins

Marginal art and writing, whether intended by the ones who designed the text or added later by industrious readers, both complements and reinterprets the text. The practice of marginal argument, called “disputatio,” was commonplace in both religious and secular works. Guilelmus Peraldus' manuscript contains a reader’s careful annotations, while Marcus Junianus Justinus' manuscript demonstrates how succeeding readers combed through the text, marking passages for themselves and future readers.

- Guilelmus Peraldus, Summa de vitiis et virtutibus, ca. 1270. Codex 003104.

- Gothic script with 14th-century marginalia.

- Marcus Junianus Julesstinus, Epitome in Trogi Pompeii historias, Italy, 15th Century. Codex 002001.

- Semi-gothic humanist script with 15th-century marginalia.

Just as written comments could add meaning to a text, so too could painted images. In 14th- and 15th-century prayer books, for example, floral motifs developed high levels of realism. Whether drawn from the Classical tradition or from native European species, such as daisies and roses, flower designs enhanced the manuscript’s visual allure. They could encourage spiritual contemplation, but they could also distract the reader from the text’s main message.

- Book of Hours, Paris, ca. 1470-1489. Codex 001910.

- Gothic script.

- Getey Book of prayers, Utrecht, ca. 1480. Codex 001969.

- Gothic script in Dutch.

Case 2. Handwriting

Handwriting expresses both individual and cultural identity. In the ninth century, scribes at Charlemagne’s imperial court developed a very clear script, closely related to the forms we use today. “Carolingian miniscule” is highly readable because it has few ligatures (conjoined letters) or abbreviations. Centuries later at the beginning of the Renaissance, humanist scholars read Carolingian books and believed that they had rediscovered original Roman texts. In hopes emulating the great Roman writer Cicero, they reworked Carolingian miniscule into Italian Humanist script. The adoption of humanist script became, across Europe, a political statement about the embrace of Classical ideals.

- Leaf from the Liber Glossarum, ca. 825. Lansburgh 3.

- Carolingian miniscule script on vellum.

- Cicero’s De Officiis, 15th century. Codex 001911.

- Italian Humanist script on paper, with 16th- and 17th-century marginal notes.

- Leaf from a Psalter, France, 12th century. Codex 002487

- This book of prayers is written in an early variety of Gothic script, called Romanesque. While Carolingian miniscule was easier to read, dense Gothic script saved on production costs, using narrow letters, sharp lines, complicated ligatures (conjoined letters), and numerous abbreviations.

- Although still used in the fifteenth century, some humanists found it virtually unreadable. “[Gothic script uses] tiny, compressed little letters that frustrate the eye, heaping and cramming everything together. . . These things the scribe himself can barely read when returning after a brief interval, while the purchaser buys not so much a book, as blindness in the guise of a book.” --Petrarch, Senilium rerum libri (Letters of Old Age), 14th century

Case 3. Printing

Although traditionally considered revolutionary, print technology in its early years was modest and retrospective. In fact, fifteenth-century printers sought to establish their legitimacy by mimicking manuscripts. These two works exemplify this process. They have many similarities even though one is an Italian manuscript on vellum and the other a German print on paper: both vary between bold, large characters and thin, small characters; both use gothic script (an older letter form) and a combination of blue and red for decorated initials. At a glance, the printed book and the manuscript book are difficult to tell apart.

- Leaf from The Nuremberg Bible, ninth edition by Antonio Koberger. Nuremberg, Germany, 1483. Rauner Incunabula 150.

- Gothic script printed on linen-fiber paper.

- Passio Sanctorum Martyrum Decem Milium. Northern Italy, 15th Century. Codex 001967.

- Gothic script handwritten on vellum

- Gothic script handwritten on vellum

These two books show the close relationship between manuscripts and printed books. Jacobus Rubeus prepared two editions of the same text, one printed on paper and one on vellum. He then sent the vellum version to illuminators, where it was decorated as a manuscript, including marginal foliage. Marginal notes were also added in a humanist script. The paper copy of the same page also has room for decorations, although they were not completed. The hybrid form of printed text with hand illustrations, and the use of vellum, remind us that print technology was initially considered an extension of manuscript culture.

- Leaf from Historia Florentina by Leonardo Bruni. Venice, Italy, 1476. Lansburgh 36. Printed by Jacobus Rubeus on vellum.

- Historia Florentina by Leonardo Bruni. Venice, Italy 1476. Rauner Incunabula 135. Printed by Jacobus Rubeus on paper.

Case 4. Gender

Women and girls played important roles as readers and producers of religious texts. Books of Hours were used by many lay worshippers, but this tiny one seems specifically designed for young aristocratic girl to learn her prayers (it has few abbreviations, for example). Saint Catherine of Siena (1347-80) took childhood learning to remarkable lengths, teaching herself to read and encountering God when she was only six years old. While she did not write about establishing a new role for women within the church, the emancipated life she led made her a model of female intellectual and spiritual capabilities.

- Book of Hours. France, 1440. MS 003197.

- Leaves from the Légende de la vie de Sainte Catherine by Raymond of Capua. Bruges, ca. 1470. Ms. 470940.

Secular documents also played important roles in the lives of women and girls. In the letter from Elizabeth Carew to her father Nicholas (a renowned member of the British royal court), she describes a dress she would like made for her. In the property settlement issued by Gonzalo de Ocampo, a Spaniard in Peru, he gives several houses to his illegitimate daughter, Maria, in an effort to stabilize her precarious social position. Both documents highlight cultural deference to a father’s authority as well as the power of the written word to intervene on a woman’s behalf.

- Letter from Elizabeth Carew to her father, Nicholas Carew. Chipping Ongar, Essex, England, January 27, 1590. Lansburgh 29.

- Grant of property by Gonzalo de Ocampo for his illegitimate daughter Maria. Los Reyes (Lima), Peru, December 14, 1552. Ms. 552664.