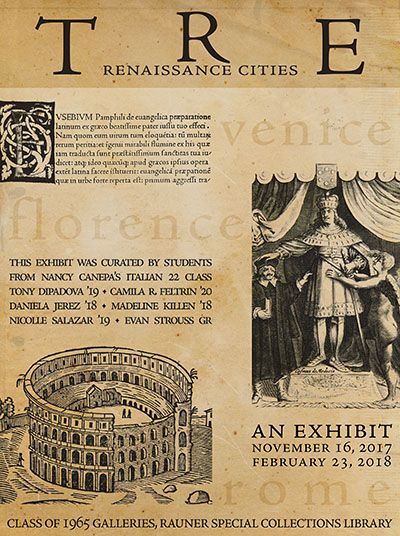

TRE: Renaissance Cities

The extraordinary cultural production of Italy from the late-fourteenth to the end of the sixteenth century—what we call the Renaissance—exerted a defining influence on Western modernity. The richness of the literature, art, and politics of this period fascinate us still today. This exhibit examines a wide range of innovative modes of expression in three Italian cities. They narrate the creative intersections and tensions between historiography, politics, and ideology in Florence; the invention of printing and changing practices of reading and writing in Venice; and architectural re-imaginings of classical antiquity in Christian Rome.

The exhibit was curated by Nancy Canepa’s “Humanism and Renaissance” class (Italian 22): Tony DiPadova ’19, Camila R Feltrin ’20, Daniela Jerez ’18, Madeline Killen ’18, Nicolle Salazar ’19, and Evan Strouss GR. It will be on display in the Class of 1965 Galleries from November 15th, 2017, through February 23rd, 2018.

You may download a small, 8x10 version of the poster. You may also download a handlist of the items in this exhibition: TRE.

Materials Included in the Exhibition

CASE ONE

Times New Venetian

When the printing press made its way from Germany to Venice shortly after its invention in the mid-15th century, printers soon realized that typefaces modeled after the Gothic hand would not sell in an Italian market. Because Italian readers were used to the lighter humanist and Italian court hands, printers made and commissioned type modeled after these hands. As Venice flourished and its influence and printed books spread throughout the European subcontinent, the clearly legible typefaces became increasingly popular. Today, the modern reader finds the Gothic hand difficult to decipher, while the humanist and italic typefaces are more familiar — we have Venice to thank for that. The goal of this case is to give a glimpse into the evolution of book styles in Renaissance Venice resulting from the adoption of the printing press. These books show different typefaces, hands, decorations, and sizes, but are only a snapshot of the various aesthetic techniques used in this time period.

- Missal. Manuscript on vellum. Venice, 1470. Codex MS 002074

-

This manuscript, a guide to Catholic mass throughout the year, created in Venice in the same year as Nicolas Jenson’s first printed book in Italy, is a beautiful example of the Gothic hand. As Jenson was hard at work replicating the humanist hand in type, the Gothic hand and the art of the manuscript remained popular throughout the European subcontinent. The rise of the printing press in Europe did not immediately eliminate interest in manuscript production; rather, the two forms of publication served different purposes and distanced themselves from each other.

-

-

Cicero. De Officiis. Manuscript on vellum. Italy, 15th Century. Codex MS 001911

-

This is a manuscript of Cicero’s De Officiis (“On Duties”), a guideline of behavior written by the great Roman orator, written in the humanist hand. Compared to the printed version of this text, this book contains only the text of Cicero. The large amount of space between letters, words and lines compared to the print version can be attributed somewhat to the differing content between the two books, but the spatial disparity also reflects the process of creating a manuscript versus a printed book. Printers had to spend hours laying out the typeface for each printed page whereas a scribe’s time and labor was more dedicated to perfecting the standardized hand; therefore, while a printer would be motivated to fit as much type as possible onto each page to increase the speed of production, a scribe would be more concerned with his script.

-

-

Cicero. Marci Tullii Ciceronis Officiorum. Venice: Per Bernarinum Benaluim, 1488. Incun 163

-

This printed book shows Cicero’s De Officiis (“On Duties”) printed in the humanist typeface. Compared to the manuscript, the pages of this version contain a small amount of Cicero’s text surrounded by annotations and analysis. This text demonstrates that printed texts attempted to distinguish themselves from manuscripts. The text is more compact and regular than the manuscript hand. Notice one aesthetic technique utilized by Renaissance printers — a clean, justified edge on either side of the block of text. Renaissance printers wished not to perfectly mimic the manuscript but to establish the printed book as its own aesthetic object.

-

-

Eusebius. De Euangelica praeparatione. Venice: Jenson, 1470. Incun 54

-

Nicolas Jenson is popularly credited as the creator of the first early Roman or humanist typeface, and this book represents his first attempt at printing a book in Venice. This edition of De Euangelica praeparatione, a work of Christian apologetics arguing the superiority of Christianity, cemented Jenson as one of history’s greatest typeface designers. It is important to note that the edges of the text are not perfectly justified. As early as one year after this book was printed, texts printed by Jenson and others have sharper margins and more condensed texts, demonstrating an increased interest in the aesthetic properties of the printed book.

-

-

Francesco Petrarca. Il Petrarca. Venice: Manutius, 1533. Presses A365pet

-

In the same way Jenson developed the humanist typeface based on the humanist hand, which was typically used for scholarly writings, Aldus Manutius developed the italic typeface based on the hand traditionally used by court scribes. This book is a collection of poems by Francesco Petrarch, the father of the Italian sonnet. The small size allowed people to carry the book with them if desired, which became a trend among the educated and fashionable people of the Renaissance.

-

-

Vittoria Colonna. Tutte le rime. In Venetia: Per Giovan Battista et Melchior Sessa fratelli, 1558. Rare PQ4620.A17 1558

-

Unlike the other books in this case, this book of poems by Vittoria Colonna, a brilliant poet and noblewoman of the Italian Renaissance, would have been printed and sold for a broader audience, evidenced by its content and choice of typeface, as well as its small, portable, economical size. This is consistent with the growing trend of poetry production during the Renaissance.

-

-

Leonardo Bruni. Historiae Florentinae populi. Venice: Iacomo de Rossi, 1476. Bifolium. Lansburgh 36

-

Leonardo Bruni is often credited as the “first modern historian” for his Florentine Histories. Based on Giovanni Villani’s New Chronicles, Bruni’s Florentine Histories take a more secular approach and divide history into periods, rather than episodically, using methods consistent with modern historians. This page is a decorated leaf from Florentine Histories.

-

CASE TWO

History of Florence

Florence was a cultural and artistic hub of Italy and the world at large during the Renaissance. The Renaissance as a whole was characterized by a focus on history and the classics, and this manifested itself in Florentine literature through the creation of new histories of Florence and beyond. This literature revolutionized the study of history: historians like Leonardo Bruni and Giorgio Vasari are often credited with being the first modern historians due to their periodic approaches. Politics influenced these historians to frame Florence as a cultural and economic center throughout Italian history in order to empower Florence as a natural heir of Roman Empire. From the Florentine Republic to the later Medicean government, these historians used their works to legitimize their respective governments to Florentines and to all Italians. In these selected works, look for the characteristic Medici crest, which consists of 6 balls on a shield; this can be found on many printed works of the period due to the grand influence of the Medici.

-

Niccolo Machiavelli. Florentini historiae Florentinae. Lugdui Batavorun: Hieronymum de Vogel, 1645. Rare DG738.13.M32 1645

- Unlike the Florentine Histories of Leonardo Bruni and Poggio Bracciolini, Machiavelli’s Florentine Histories focus on internal conflicts between those in control of the Florentine government. It is also of note that these histories largely ignore any abuse of power by the Medici family in their rise to power. These histories are, in fact, dedicated to Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici and the Medici crest can be seen on the cover page.

-

Giovanni Villani. Storia di Giovanni Villani. Florence: Filippo & Iacopo Giunti, 1587. Presses G438Vi

- Giovanni Villani famously wrote the New Chronicles, an episodic medieval history of Florence covering from biblical times until 1346. The cover page of this history proudly claims Villani as a “Florentine Citizen,” with “license from the appropriate Florentine authorities.”

-

Frosino Lapini. Institutionum florentinae linguae. Florence: Iunctas, 1569. Presses J969l

-

Lapini’s works focused on the vernacularization of classic and contemporary texts, the codification of Italian grammar and rhetoric, and pedagogical reflection. This book in particular served as a guide on Italian rhetoric and grammar, written specifically to facilitate the instruction of Italian to the public abroad, as explained by the dedicatory page, dedicated to Giovanna d'Asburgo, Francesco I de Medici's first wife, and printed by the Giunti family.

-

-

Giorgio Vasari. Le vite de piu eccelleni pittori, scvltori, e architecttori. Florence: Giunti, 1568. Rare N6922.V2 1568

-

Vasari's three volume collection consists of artist biographies and praises, inspired by his belief that the Renaissance had allowed for the rebirth and perfection of art. Considered to be the first book on art history, Vasari published two editions, the first in 1550 and the second, an expanded and illustrated version, displayed here, in 1568. Vasari's writings had an important influence on the attention given to the artists behind great works, served as a model for future biographers and art historians, and solidified the important role of Florentine art in the Renaissance.

-

-

Silvano Razzi. Vite di qvattro huomini illustri. Firenze: Stamperia de Giunti, 1580. Presses J969r

-

Printed by the Giunti family of Florence, Razzi's book consists of the biographies of four influential figures in Florence: Farinata degli Uberti, Gualtieri di Brienne, Salvestro de' Medici, and Cosimo de' Medici. The men featured in Razzi’s biographies were all important nobles with a role in the politics of Florence; their positions ranged from military leaders to provost of the city of Florence to the founder of the Medici political dynasty in Florence. A later version of this work includes the biography of Francesco Valori, an artist.

-

CASE THREE

Roma: Com'é e Com'era [Rome: How It Is and How It Was]

The term “Roma sparita,” often used to describe the eternal city, might be translated best as the “Rome that has disappeared.” Indeed, descriptions of Rome during the Renaissance have a tenuous hold on accurately depicting the lived realities of the city. The construction of Rome is the theme of this case: both in the literal sense of its built textures and its more figurative meaning, namely, its construction in the imaginations of its inhabitants and visitors. We have attempted to craft a narrative of Renaissance imaginations of the city, a narrative that here begins with studies of the ancient buildings and their smallest components, such as the Pantheon and the Colosseum, and culminates in a more modern city of the Catholic faith, embodied by the extravagant Saint Peter’s Basilica.

To truly understand Humanistic Rome – in which the trademark value was an idealization of the past and the practice of restructuring it to better fit the present – it is important to consider not only the physical space of its construction but also the abstract sense of space that represents where humans stand. Right now, in this very room in Rauner Library, you can look up at its Palladian columns and feel an instant connection to Rome, where identical columns were utilized in the construction of its majestic buildings.

-

Giovanni Giacomo Rossi. Insignium Romae. Roma, 1684. Rare NA1123.R6 A47 1684

-

This book presents etchings of the exteriors and interiors of Renaissance Roman churches in astonishing detail. Its Latin title might urge readers to imagine these monuments to Christianity in the same context of the marvels of the ancient Roman empire. “Insignium” here means “most notable.” Pictured here is an cross-sectional illustration of the interior of Saint Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican City. Notice the attribution to the architect above the diagram: Michelangelo.

-

-

Giacomo Lauro. Antiquae Urbis splendor. Roma: Vitali Mascardi, 1612-1628 [i.e. 1637]. Rare NA1120.L3 1637

-

Presented here is a map of “modern Rome,” which unofficially marks the beginning of the latter, modern half of this book – a series of illustrations of Roman marvels, both ancient and contemporary. Notice here the monuments that are privileged most prominently as “belonging” to the 17th century city: a colosseum in ruins, the giant St. Peter’s Basilica (just recently finished at the time of publication), the many ancient obelisks and columns dotting the city amidst more modern buildings.

-

-

Francesco Albertini. Opvscvlum de mirabilibus nouae & ueteris Urbis Romae. Roma: Iacobum Mazochium, 1510. Rare DG805.A534 1510

-

This guidebook by Francesco Albertini was the first of its kind, in that it dedicated a significant portion of its text to a modern Rome. Earlier guidebooks from the 15th century and earlier, by contrast, were directed at pilgrims who spent their time hopping from one church to the next and offered mystifying legends about the ancient ruins, in lieu of archaeological facts. Unlike later guides (including the Leoni guidebook in this case), this book features no images, suggesting that the target audience was the highly educated tourist. We have presented here the table of contents for the third and final part of Albertini’s guidebook, which offers a very different itinerary for the tourist in Rome from the itineraries preceding it. Listed on this page, for example, you’ll find the papal palace and library, alongside the fountains and bridges of Renaissance Rome.

-

-

Marco Vitruvius Pollio. I Dieci Libri Dell’Architettura. Venice: Ioannis de Tridino, 1511. Red Room 871 V92 1511

-

Marco Vitruvius Pollio (c. 80-70 B.C.—c. 15 B.C.), known simply as Vitruvius, was a Roman author, architect, and engineer. He is famous for discussing the idea of perfect proportion in architecture. He is known as the first Roman architect, but in reality he is the first to have written surviving records of his field. This text, The Ten Books of Architecture, was first printed in Latin in the early 15th century and this edition is from 1511, including annotations, in Italian, by an unknown author. This treatise is the only one of its kind to survive from antiquity and has been utilized by every architect that followed. The page displayed includes Vitruvius’s calculations for the inside of the Pantheon, including a diagram of a sun dial to consider how varying hours of the day would affect the quality of light inside.

-

-

Andrea Palladio. I Quattro Libri Dell’Architettura. Venice: D. de’ Franceschi, 1570. Rare NA2515.P25 1570

-

Andrea Palladio (1508-1580) is regarded as the greatest architect of the Renaissance. The Venetian-born man was responsible for the construction of hundreds of structures throughout Italy, including many in the city of Rome. As evident by the title of this text, The Four Books of Architecture, Palladio based his treatise on that of Vitruvius (displayed above). Palladio was a great admirer of the Roman architect and diligently studied his texts and his work before publishing his own works. The “Palladian style” became a global sensation, conveying the importance of rationality—clarity, order, and symmetry—as well as paying homage to the works of classical Roman antiquity, especially Vitruvian architecture. The page displayed above is a perfect example of this, displaying the concept for the exterior of the Pantheon, from the columns to the materials necessary for the project. It is important to note that this text is in the vernacular Italian and not the Latin reserved for the elite.

-

-

Pietro Leoni. Les merveilles de la ville de Rome. Rome: Vital Mascardi, 1637. Rare DG805.L466 1637

-

This text, published in French, was created as a guidebook for Renaissance tourism. Pietro Leoni’s guidebook is thorough, including visual aids for nearly every page (displayed above is the Roman Coliseum). The book includes a section that depicts the seven wonders of the world, among them the walls of Babylon and the pyramids of Egypt, giving the reader a more globalized view of their world. There are also tables in the back that list all the emperors and rulers of Roman history, as well as all the popes. Translated into English, the guidebook refers to “The Marvels of the City of Urban Rome,” making it clear to the Renaissance reader that they were embarking on a magnificent tour through this city.

-