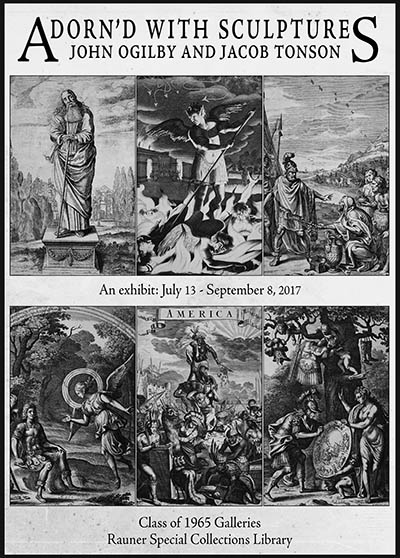

"Adorn'd With Sculptures": John Ogilby and Jacob Tonson

In many important ways, the modern English publisher was born in the second half of the 17th century. The printer/publisher model that had been established with the introduction of the printing press, where an individual armed with a printing press often acted as printer, editor, distributer, promoter, and sometimes even author, gave way to a professionalized group of individuals largely dedicated to the acts of production, distribution, and promotion. These new publishers evolved into intermediaries between authors and the reading public as they cultivated a new role in the realm of literary production.

This exhibit looks at two major London publishing houses that illustrate this transition: the firm headed by John Ogilby from 1650 to 1676; and the family publishing empire founded the year of Ogilby’s death by Jacob Tonson. Ogilby wrote, translated, and compiled works to feed his press, one of his many sources of income. He had a flair for the extravagant and produced many monumental texts of the 17th century. Tonson concentrated on literary production. Writing very little himself, he gleaned profit from promoting the literary talents of others. In so doing, he established his firm as a modern publishing giant that came to dominate London publishing for over a century. Curiously, many of the volumes issued by both Ogilby and Tonson look remarkably similar—in fact, Tonson’s edition of Virgil relies on the original plates Ogilby commissioned for his translation.

The exhibit was curated by Jay Satterfield and Morgan Swan; it is on display in the Class of 1965 Galleries from July 13, 2017, to September 8, 2017.

You may download a small, 8x10 version of the poster: Adorned-with-sculptures.jpeg. You may also download a handlist of the items in this exhibition: Adornd-with-sculptures_handlist.pdf.

Materials Included in the Exhibition

Case 1. A Freewheeling Entrepreneur

John Ogilby’s professional life reads at times like a long series of never-ending entrepreneurial successes and failures. Born in 1600, he soon became the primary bread-winner for his family after his father’s imprisonment. After a succession of savvy business dealings, he was able to establish his own dancing school. After a catastrophic injury ended his dancing career, he landed a tutorship position with a high-ranking government official in Ireland. Soon after, Ogilby founded the first theatre in Ireland and became Deputy Master of the Revels in 1637.

Out of work after the Irish Rebellion of 1641, Ogilby learned Latin and translated Virgil into English verse. Its success inspired him to establish a publishing business in London in 1650 in order to produce and distribute his own works. In 1660, Ogilby used his social network to obtain a commission for writing speeches and songs to be used at the coronation of Charles II. By the time of his death in 1676, Ogilby had been named Master of the Revels in Ireland and had been appointed His Majesty’s Cosmographer and Geographic Printer.

Ogilby’s numerous business interests and pursuits over the course of his life suggest that, for him, printing was one of many means to an end. His publishing house was simply another revenue stream that allowed him to maximize the profits to be gained through his translation work. In this, Ogilby was representative of many publishers of the age; It wasn’t until Jacob Tonson founded his publishing house in 1676, the same year that Ogilby died, that publishing would take on a more focused and distinctive professional identity.

-

John Ogilby. America: Being the Latest, and Most Accurate Description of the New World. London: Printed by the author, 1671. Rare DS257 .O47 1673

-

John Ogilby. Itinerarium Angliae; or, A Book of Roads, Wherein are Contain’d the Principal Road-ways of His Majesty’s King of England and Dominion of Wales. London: Printed by the author, 1675. Rare G1808 .O3 1675

-

John Ogilby. Homer, his Odysses: Translated, Adorn’d with Sculpture, and Illustrated with Annotations by John Ogilby. London: Printed by James Flesher for the author, 1669. Depository PA4025.A5 O5

Case 2. The Modern Publisher

In 1676, Jacob Tonson followed his brother Richard into the field of publishing by establishing his own publishing firm. For the next twenty years, the two occasionally co-published works, and Richard’s son, also named Jacob, joined his namesake in the business around 1700. Together, the two Jacobs built a large-scale publishing firm that specialized in important literary works of the time.

With his inheritance in hand, Jacob the elder was able to acquire the publishing rights to Shakespeare’s plays along with the rights to Milton’s Paradise Lost. He applied some of Ogilby’s flair for the dramatically illustrated book to produce the first copy of Milton with heroic illustrations. With substantial literary properties serving as a reliable revenue generating backlist, Tonson was able to build on existing relationships and expand his firm to become a key publisher of new materials, most notably the works of John Dryden and Aphra Behn.

Tonson’s social world helped to feed his presses (and his authors). He was one of the founders of the Kit-Kat Club, a group of elite gentlemen and men of letters most of whom were devoted to the Whig party’s goals of a limited monarchy and a strong parliament. The club helped Tonson develop patronage and financial support for his authors. It created an environment where benefactors and creators could meet and supply Tonson with a steady stream of material to publish.

-

John Dryden, editor. The Annual Miscellany for the Year 1694. London: Jacob Tonson, 1694. Hickmott 621

-

Tonson conceived of a regular series of miscellanies (this one being the fourth for 1694), as a regular income producers for himself and for Dryden.

-

-

William Congreve. The Way of the World, a Comedy. London: Jacob Tonson, 1700. Rare PR3364 .W3 1700

-

Congreve was a prominent member of the Kit-Kat Club and an example of Tonson’s attention to theater.

-

-

Aphra Behn. Sir Patient Fancy: A Comedy. London: Jacob Tonson, 1678. Rare PR3317 .S57 1678

-

Tonson entered publishing in the hey-day of restoration comedy and promoted key authors like Aphra Behn.

-

-

John Milton. Paradise Lost. London: Jacob Tonson, 1688. Rare PR3560 1688

-

Tonson’s edition of Paradise Lost was the first to adorn the poem with “sculptures.” He claimed to have made more money off of Milton than any other author.

-

-

John Dryden. Eleonora: A Panegyrical Poem. London: Jacob Tonson, 1692. Hickmott 625

-

William Shakespeare. The Works of William Shakespeare. London: Jacob Tonson, 1709. Hickmott 5

-

Each play in Tonson’s collection of Shakespeare is “adorn’d with cuts.” The frontispiece for Hamlet has been hand colored.

-

Case 3. The Faces of Aeneas

England’s 17th-century political turmoil affected both Ogilby and Tonson. Ogilby was a staunch supporter of the king while Tonson was a Whig who opposed monarchical absolutism. Their political leanings surface subtly in the illustrations of their respective printings of Virgil’s Aeneid.

At least one scholar has suggested that Ogilby’s Aeneid, printed in 1654, pays homage to Charles II in its representations of Aeneas, whose round face and black mustache bears a strong resemblance to the king in his youth. It is probably not a coincidence that Ogilby was tapped to participate in the planning of Charles’s coronation in 1660; that same year, he also published his translation of Homer’s Iliad, which he dedicated to Charles.

Tonson’s edition of the Aeneid is a more complex political creature than Ogilby’s for many reasons. As a founder of the Kit-Cat Club, he would not have been an eager supporter of Charles II. However, Tonson purchased the original engraving plates from Ogilby’s Aeneid for use in Dryden’s translation of Virgil’s works, which meant potentially including images of Charles II in his 1694 edition. As a result, Tonson paid an anonymous engraver to alter the images of Aeneas that looked most like Charles II so that the monarch’s tell-tale mustache was eliminated or obscured.

Moreover, John Dryden was Catholic and a staunch supporter of the recently deposed James II, to the extent that he had openly refused to take the oaths of allegiance to William III and Mary II when they took the throne in 1689. As such, Dryden refused to dedicate his translation of the Aeneid to William. This introduced a potential problem for Tonson, whose ability to publish in England relied on the king’s explicit approval. As a solution, to counteract Dryden’s Jacobite leanings in the text, Tonson hired an anonymous engraver to alter further some of Ogilby’s original plates of Aeneas so that the Trojan hero would share William III’s distinctive Roman nose.

-

John Dryden. The Works of Virgil. London: Jacob Tonson, 1697. Rare PA6807.A1 D7 1697

-

John Ogilby. The Works of Publius Vergilius Maro. Printed by T. Warren for the author, 1654. Hickmott 543

-

Unknown Artist. Line Engraving of King Charles II, [165-]. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

-

Unknown Artist. Line Mezzotint of King William III, 1695. Published by John Smith, after Sir Godfrey Kneller. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London.