|

|

|

| Best of all was riding bikes. | |

Note: The following description of German word order is conceptual in nature. Those who would prefer a more mechanical set of rules would be better served by linking to a set of prescriptive instructions for German word order. That site and this one, despite their differences in approach, overlap considerably.

English tends to rely mostly on word order to indicate the grammatical function of a word or phrase, while German uses inflections. The German endings, such as those indicating the nominative, accusative, dative, and genitive cases in three different genders, allow for some greater flexibility in clause construction. Nevertheless, German word order is extremely important, even when it is not vital to meaning, and its correctness plays a major role in how a foreigner's command of the language is evaluated.

At the same time, word order is an infinitely complex aspect of language, never wholly mastered by non-native speakers. Very few rules cover all possibilities, and context often trumps other considerations. When Robert Frost writes, "Something there is that doesn't love a wall," it's poetic; if someone with a foreign accent says the same thing in conversation, it sounds like Yoda.

German Word Order in Main Clauses (Hauptsätze)

The following description of German word order is based on the structure of main clauses, also called independent clauses. A "main clause" has a subject and a predicate and can form a complete sentence that is able to stand alone. It can take a number of forms, but we will begin with the simple declarative sentence (der Aussagesatz). Here are some English examples:

- "You are wrong."

"The square of the hypotenuse of a right triangle is equal to the sum of the squares of the two adjacent sides."

"It looks like rain."

"An invitation to a Sunday midday meal in Germany can include a leisurely walk, coffee and cake later in the afternoon, and an evening supper."

"He ought to know that." - "Der Mann beißt den Hund" (The man bites the dog)

"Die Männer beißen den Hund" (The men bite the dog)

"Ich biss den Hund" (I bit the dog). -

"Der Mann beißt den Hund"

"Den Hund beißt der Mann." If the finite verb has a separable prefix, the prefix goes to the end:

abholen: Wir holen meine Mutter am Bahnhof ab. We're picking my mother up at the train station.

ankommen: Der Zug kommt auf Gleis 4 an.The train is arriving on Track 4.

aufessen: Die Kinder essen alles auf.The children eat up everything.

hinauswerfen: Sie wirft sein Buch zum Fenster hinaus.She throws his book out the window. Another example of such an additional element is a past participle, used to construct the present perfect tense. Here in this case the finite verb is the auxiliary, "haben", which stands in the second position, while the past participle of the verb "beißen" ("gebissen") comes at the end:

Der Mann hat den Hund gebissen (or: Den Hund hat der Mann gebissen.) The man bit the dog. And here is the same sentence in the future tense, whereby the finite auxiliary is "werden", and the verb "beißen" is in the infinitive:

Der Mann wird den Hund beißen (or: "Den Hund wird der Mann beißen) The man will bite the dog. The same principle (finite verb in second position, infinitive at the end) applies to verb phrases that employ modal auxiliaries:

Der Mann will den Hund beißen (or: "Den Hund will der Mann beißen) The man wants to bite the dog.

Der Mann wird den Hund beißen wollen. (or: "Den Hund wird der Mann beißen wollen).The man will want to bite the dog. Likewise for predicates consisting of other two-verb combinations:

Sie geht heute einkaufen. (or: Heute geht sie einkaufen). She is going shopping today.

Mein Bruder lernt jetzt fahren. (or: Jetzt lernt mein Bruder fahren).My brother is learning to drive now.

Meine Schwester lernte viele interessante Leute kennen.My sister got to know a lot of interesting people.

Ihr Kind geht gewöhnlich früh schlafen.Her child usually goes to bed early. One common two-verb combination uses "lassen".

Double-infinitives in the perfect tenses:

When in one of the perfect tenses, modal auxiliaries or verbs like sehen, hören, helfen, and lassen are combined with another verb, they form double-infinitives, which go to the final position:Ich habe nichts sehen können. I couldn't see anything.

Wir hätten das nicht sagen sollen.We shouldn't have said that.

Der Prinz hat Rapunzel ein Lied singen hören.The prince heard Rapunzel singing a song.

Er hat ein neues Haus bauen lassen.He had a new house built. I.c. Verb Complements Made from Other Parts of Speech:

The German predicate can also contain other parts of speech that combine with the verb conceptually. These "verb complements", found at the end of the clause, are necessary parts of the predicate's meaning, not just augmentations. [Consider the German-inspired Pennsylvania Dutch formulation, "Throw the cow over the fence some hay", in which the operative concept is "throwing hay (to)"]. Here are some common examples:Sie spielt gern Tennis. She likes to play tennis.

Ich spiele fast jeden Tag Schach.I play chess almost every day.

Er fährt gern Ski.He likes to ski.

Ich nehme lieber in der ersten Reihe Platz.I prefer to sit (take a seat) in the first row.

Sie fährt gern Fahrrad.She likes to ride a bike. In each of these examples, the predicate is made up of the finite verb (in second position) and the object that is necessary to its meaning (at the end). The concepts being presented are not simply verbs ("spielen" and "nehmen") that are then modified by their objects, but rather conceptual entities: "Tennis spielen," "Schach spielen," "Ski fahren", "Platz nehmen", and "Fahrrad fahren." The nouns "Tennis," "Schach," "Ski," "Platz," and "Fahrrad" are placed at the end of the clause just as if they were separable prefixes. In fact, the last example could have expressed as: "Sie fährt gern rad", since "radfahren" and "Fahrrad fahren" are synonymous.

Such complements can be made up of more complex combinations:

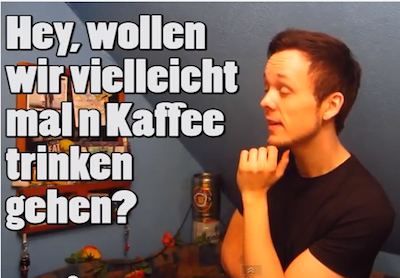

Wir gehen nach der Vorlesung Kaffee trinken. We're going for coffee after the lecture. Here, "Kaffee trinken gehen" is the idea.

Colloquial speech often produces imaginative coinages to create new verbal concepts:

Sie geht heute Abend mini. She's wearing a mini-skirt tonight. I.d. Qualifiers (Non-Obligatory Elements):

Those elements that are not necessary to the "verbal idea" do not go to the end. They occupy positions appropriate to their function within the sentence (e.g. as an accusative object; see below).Note the contrast between these two sentences:

Ich fahre gern Auto. I like to drive (a car). Ich fahre dieses Auto gern. I like to drive this car. In the first sentence, the concept is "Auto fahren." In the second, the concept is "fahren" (modified by "gern"), and "dieses Auto" is the object - what I like to drive - and hence it is not positioned at the end as a verbal complement.

Another example:

Sie sieht ihn oft im Supermarkt. She often sees him in the supermarket. Here the "ihn" is not a necessary part of the predicate; rather, it modifies the act of seeing (as do "oft" and "im Supermarkt").

In the following example, however, "das Sandmännchen" [= the name of a children's tv show] is a defining element of the children's activity: "das Sandmännchen sehen".

Die Kinder sehen fast jeden Abend "Das Sandmännchen". The children watch "The Sandman" almost every evening. Note that it is also possible to say: "Die Kinder sehen 'Das Sandmännchen' fast jeden Abend", but this variation creates a different concept. Here 'Das Sandmännchen' is merely the show that the children watch, the object of their "seeing," and "fast jeden Abend" becomes the more important information.

He has visions every day. ["Visionen haben" is the verbal idea] I.e. The Predicate Nominative and Predicate Adjective:

English-speakers may feel more comfortable with this way of thinking about the "verb complement" when considering the "predicate nominative":Er ist meistens ein guter Freund. He is mostly a good friend. and the "predicate adjective":

In der Nacht sind alle Katzen grau. At night all cats are gray. In these examples, German indicates in two ways that "ein guter Freund" and "grau" are part of the predicate: through inflection (in the case of the noun "friend," by putting him in the nominative; in the case of the adjective "gray", by giving it no ending) and through position (both "friend" and "gray" are placed at the end, indicating that they are part of the "verbal idea": "Freund sein"; "grau sein").

Other examples:

"fleißig sein": Sie ist in der Schule sehr fleißig. She's very industrious in school.

"unhöflich sein": Bist du auch mit deinen Freunden so unhöflich?Are you that impolite with your friends, too?

"zu Hause sein": Sie ist meistens zu Hause.She's usually home. In German the predicate nominative is formed not only with the verb "sein" ("to be"), but also with "werden" ("to become") and "bleiben" ("to remain"). One could, in a way, say that these three verbs take a nominative object:

"mein vierter Mann werden": Er wurde nach diesem großen Abenteuer mein vierter Mann. He became my fourth husband after this great adventure.

"mein bester Freund bleiben": Er bleibt trotz allem mein bester Freund.Despite everything he remains my best friend.

II. The Position of the Nominative Subject.

The subject often occupies the first position, preceding the finite verb:

Der Laden bietet seinen Kunden ein echtes Schnäppchen. The store offers its customers a real bargain. Das Hotel serviert seinen Gästen jeden Morgen ein opulentes Frühstück. The hotel serves its guests an opulent breakfast every morning. But the speaker always has the option of emphasizing some other element of the sentence (except for the verb) by putting it in the first position. In that case, the subject follows the verb (in third position):

Seinen Kunden bietet der Laden ein echtes Schnäppchen. Ein echtes Schäppchen bietet der Laden seinen Kunden.

Jeden Morgen serviert das Hotel seinen Gästen ein opulentes Frühstück.Seinen Gästen serviert das Hotel jeden Morgen ein opulentes Frühstück. Ein opulentes Frühstück serviert das Hotel seinen Gästen jeden Morgen. In German such inversions are part of ordinary spoken and written discourse. Note, however, that ambiguities can arise when neither the subject nor accusative object are masculine singular. The meaning of "Den Mann beißt der Hund" is clear from the inflections; with "Die Katze beißt die Frau", it is not. Here it is the word order that suggests who bites whom.

German ears prefer pronouns to precede nouns wherever possible, even when the noun is the subject in "third position". Thus "Der Mann rasiert sich jeden Tag gründlich." (The man shaves himself thoroughly every day) becomes, when the order is inverted: "Jeden Tag rasiert sich der Mann gründlich."

Similarly: "Gestern ist ihm die Frau zweimal begegnet." (Yesterday the woman encountered him twice).- Morgen sollten wir schwimmen gehen. Tomorrow we ought to go swimming.

- (English also permits this inversion.)

Am Freitag kannst du ihm das Buch geben. On Friday you can give him the book.- (Also permitted in English.)

- Das Buch kannst du ihm am Freitag geben. You can give him the book on Friday.

- (Here the inversion is not possible in English

without further elements:

The book [is what] you can give him on Friday.)

- Mit dem Bus fährt sie am liebsten. She most prefers to go by bus.

- (No such inversion does English permit.)

- Sehr gut hast du das heute Abend gespielt. You played that very well tonight.

- (It would be possible to say in English, "Tonight you played that very well," or even,

with added emphasis, "That you played very well tonight," but not: "Very well you played that tonight.")

- Arbeiten will ich erst nach dem Essen. I don't want to work until after dinner.

- (Even the infinitive can be in the first position.1)

- Gesagt habe ich das nie. I never said that.

- (Here the past participle is first.)

- Weil es regnet, bringen wir den Schirm mit. Because it's raining, we're bringing the umbrella along.

- (Even a dependent clause can occupy the first position.)

- Ohne zu wissen warum, wirft sie es in den Papierkorb. Without knowing why, she throws it into the wastebasket.

- (Here the first position contains an infinitive clause.)

- "Es" can of course serve as a nominative pronoun that substitutes for a neuter noun.

In this function, it acts like any other subject - i.e., it moves to the third position when not in the first:

Ich habe das Buch gekauft. → Es war teuer. → Teuer war es. I bought the book. It was expensive. - "Es" can also be part of an expression in which it is the subject of "an impersonal verb." Here, too, it acts like a standard pronoun subject:

Es schneit jetzt. → Jetzt schneit es. It is snowing. Es ist kalt. → Kalt wird es. It is cold. Es wird dunkel. → Dunkel wird es. It is getting dark. Es gibt jetzt ein Problem. → Jetzt gibt es ein Problem. Now there is a problem. Es gibt zwei Möglichkeiten. → Zwei Möglichkeiten gibt es. There are two possibilities. Es ärgert mich, wenn er schmatzt. → Mich ärgert es, wenn er schmatzt. It annoys me when he smacks his lips. In contrast to these preceding examples, German also has an "introductory es" that functions as a "false subject." This "es" can be found only in the first position. With inverted word order it disappears. Note that it is not a "true subject," in that it does not determine the form of the finite verb. Its only purpose is aesthetic. The "true subject," which is always a noun (as opposed to a pronoun), follows the finite verb in the third position:

Es spielen keine Mädchen in der Mannschaft. → In der Mannschaft spielen keine Mädchen. There are no girls playing on the team. Es steht ein Mann vor der Tür. → Ein Mann steht vor der Tür. There is a man standing in front of the door. Es kommen viele Gäste. → Viele Gäste kommen. A lot of guests are coming. The introductory "es" is particularly common in the passive voice, especially with verbs that take the dative. Here, however, it is the subject:

Es wird uns beiden geholfen. We are both being helped. Es wurde ihm noch eine Chance gegeben. He was given another chance. At the same time, even when it is the true subject, this "es" can be thought of as place-holder. When another element occupies the first position, it usually disappears:

Es wird mir geholfen. → Mir wird geholfen. I'm being helped. Es wurde ihr oft gedankt. → Oft wurde ihr gedankt. She was often thanked. A similar use of the "introductory es" can be found in the so-called impersonal passive, which can denote general activity, often used with an intransitive verb. When the word order is inverted, the "es" normally disappears. Note that such an inversion is not possible when the finite verb is a modal auxiliary:

Es wurde die ganze Nacht getanzt. → Die ganze Nacht wurde getanzt. There was dancing going on all night. Es wird bei uns zu Hause viel gelacht. → Bei uns zu Hause wird viel gelacht. At our house there is a lot of laughter. Es wird hier selten geraucht. → Hier wird selten geraucht. There isn't much smoking done here. Es darf nicht geredet werden. There's no talking allowed.

At T-Com the prices are falling. T-Com's new Wish-What-You-Want prices are coming March 1st. Then you can decide yourself how you want to save on telephoning. - Te represents time expressions - when something happens: "heute", "oft", "in einer Stunde", etc. If there is more than one expression in this category, the general precedes the specific: "Montag um 8 Uhr."

- Ka indicates why something happens, under what circumstances, or with what consequences: "aus Versehen" [by mistake]; "bei gutem Wetter" [in good weather]; "zu meinem Erstaunen" [to my amazement].

- Mo describes manner - how it happens: "traurig" [sadly]; "mit Begeisterung" [with enthusiasm]; "sehr schnell" [very fast]; "ohne Verzögerung" [without delay].

- Lo indicates location - where it happens: "zu Hause"; "in die Stadt"; "in der Stadt"; "über die Straße".

III. Noun or Pronoun Objects:

As a general rule, if the nominative subject is in the first position, objects of the verb phrase follow the finite verb:

Er schlägt seine Feinde zu Apfelmus. He beats his enemies to a pulp [to apple sauce]. Sie spült das Geschirr schnell ab. She does the dishes quickly. Ich habe mein Referat schon gestern fertiggeschrieben. I already finished writing my paper yesterday. Wir kennen sie ziemlich gut. We know them pretty well. Sie antwortet dem Mann sehr freundlich. She answers the man in a friendly way. Wir sind meiner Mutter in der U-Bahn begegnet. We ran into my mother in the subway. Du widersprichst mir jedes Mal. You contradict me every time. Ich bestelle das bei meinem Weinhändler. I order that from my wine dealer. Mein Vater rasiert sich jeden Morgen. My father shaves every morning. The Relative Placement of Dative and Accusative Objects:

a. Again, when an accusative noun object is an obligatory part of the predicate's meaning, it is positioned at the end:

Ich gebe dir bei nächster Gelegenheit ein besseres Buch. I'll give you a better book at the next opportunity. [The predicate = "ein besseres Buch geben"] b. When a dative (indirect) noun object and an accusative (direct) object are next to or near each other, the dative noun comes first:

Sie gibt ihrem Mann einen Kuss auf die Glatze. She gives her husband a kiss on his bald head.

Er schickt seiner Mutter eine Email.He sends his mother an e-mail.

Ich glaubte meinem Vater alles.I believed everything my father said.

[Note: "alles" is not a pronoun.]c. If the accusative and dative are both pronouns, the accusative precedes:

Ich zeige es dir. I'll show it to you. Sie erzählt sie ihnen. She tells it to them. d. If one object is a pronoun and the other a noun, the pronoun always precedes:

Sie verspricht es ihrem Vater. She promises it to her father. Ich schlage dir etwas Besseres vor. I'll suggest something better to you. e. While most verbs distinguish direct and indirect objects through a combination of the accusative and dative, fragen, kosten, and lehren do not follow this pattern; both objects are accusative. However, these two objects come in the order you would expect:

Darf ich dich etwas Persönliches fragen? May I ask you something personal? Das hat den Mann eine Menge Geld gekostet. That cost the man a bunch of money. Sie lehrt ihren Bruder die deutsche Sprache. She's teaching her brother the German language. A short adverb of time (see the next section) may precede a noun object, but not a pronoun:

Ich gebe dir heute ein teures Geschenk. I'm giving you an expensive present today. Es gibt heutzutage keine richtige Lösung zu diesem Problem. There's no real solution to this problem nowadays. Man sieht immer noch Menschen, die beim Fahren texten. One still sees people who text while driving. IV. The Mid-Field (das Mittelfeld):,

What German grammarians call the Mittelfeld ("mid-field") is found after the finite verb (or else after the subject, when it is in the third position, or else after objects that immediately follow the finite verb) and before the verb complement. It contains the qualifiers that modify the verb. Most grammar texts describe this part of the declarative sentence as containing the categories of "time - manner - place" and require them to appear in that order. (E.g., Wir sind heute mit dem Bus nach Hause gefahren.) While not wholly wrong, that scheme is too simple. Modern German grammarians have developed a more nuanced scheme (which is designated by the Eselsbrücke [= mnemonic device], "Tee-Kamel"):

Te (temporal) Ka (kausal) Mo (modal) Lo (lokal)

Here is an example of an admittedly unlikely declarative sentence, one that contains all of the aforementioned elements. It has a subject ("viele Ehemänner") in first position, a predicate consisting of a finite verb ("sehen") in the second position and the remaining part ("alle Sportsendungen") in the final position. The "mid-field" contains the modifying expressions in the "expected" or "standard" order: Te ("jeden Sonntag") - Ka ("zum Entsetzen ihrer Frauen") - Mo ("völlig passiv") - Lo ("in ihrem Lieblingsessel"):

Viele Ehemänner sehen jeden Sonntag zum Entsetzen ihrer Frauen völlig passiv in ihrem Lieblingssessel alle Sportsendungen. Many husbands, to their wives' disgust, watch all the sports shows completely passively every Sunday in their favorite easy chair. Note what nuances of meaning are created when the "expected" order is altered, when the "Mo" expression, for example, "völlig passiv" is relocated (the way that any other element could be):

Völlig passiv sehen viele Ehemänner jeden Sonntag zum Entsetzen ihrer Frauen in ihrem Lieblingssessel alle Sportsendungen. Viele Ehemänner sehen völlig passiv jeden Sonntag zum Entsetzen ihrer Frauen in ihrem Lieblingssessel alle Sportsendungen. Viele Ehemänner sehen jeden Sonntag völlig passiv zum Entsetzen ihrer Frauen in ihrem Lieblingssessel alle Sportsendungen. Viele Ehemänner sehen jeden Sonntag zum Entsetzen ihrer Frauen in ihrem Lieblingssessel völlig passiv alle Sportsendungen. A further possibility is available in spoken or literary German:

Viele Ehemänner sehen jeden Sonntag zum Entsetzen ihrer Frauen in ihrem Lieblingssessel alle Sportsendungen, völlig passiv. Style-Tip: Especially in spoken German, comparative phrases using als or wie often go to the end of a clause:

Du hast das besser gemacht als dein Bruder. You did that better than your brother.

Sie ist so groß geworden wie ihre ältere Schwester.She's gotten as big as her older sister. V. Negations

I. kein

Nouns without a definite article are negated by the use of kein, which receives the same endings as the other "ein"-words:Du bist kein guter Freund. You are not a good friend. Sie hat keinen festen Freund. She doesn't have a steady boyfriend. Er spricht kein Deutsch. He doesn't speak any German. Ich habe kein Geld bei mir. I don't have any money on me. When negating two or more nouns, English uses "or" as the coordinating conjunction, while German is more likely to use "und," conceptually conjoining the negated items:

Wir haben keine Äpfel und keine Bananen. We don't have apples or bananas. Er hat keine Zeit und kein Geld. He has no time or money. If the idea is "neither ... nor", however, German uses "weder ... noch" instead of "kein":

Wir haben weder Äpfel noch Bananen. We have neither apples nor bananas. Er hat weder Zeit noch Geld. He has neither time nor money. II. nicht

The placement of nicht to negate a clause is more an art than a science, but determining just what is being negated will go a long way to producing an appropriate structure. (Those preferring to follow a list of set rules would be best served by linking to these prescriptive instructions for negation).The key concept to grasp is that the nicht precedes the element that it is intended to revoke. If the sentence contains a predicate adjective or predicate noun, that is most likely what is being nullified:

Du bist nicht sehr freundlich. You're not very friendly. Sie ist nicht meine Schwester. She's not my sister. Here are further examples of the placement of nicht so that it negates the key part of the sentence:

Er wäscht sich nicht sehr oft. He doesn't wash very often. Wir sind nicht immer zu Hause. We aren't always home. Er tut das nicht gern. He doesn't like to do that. Sie fährt nicht zu schnell. She doesn't drive too fast. Sie arbeitet nicht hier. She doesn't work here. Ihr Auto steht nicht da. Her car isn't there. Sie kommen nicht zu mir. They're not coming to my house. Er joggt nicht vor dem Essen. He doesn't go jogging before dinner. Wir fahren nicht am Montag. We're not going on Monday. Nicht at the end of the Mid-Field: In each of the above examples, specific information is negated. "Wir fahren nicht am Montag" states that the day on which we are not driving is Monday, but we might possibly be going on a different day. The listener might well expect this assertion to be followed by "sondern ..." (but rather ...). If, on the other hand, we wish to negate the whole general idea of the sentence, we put the "nicht" after the modifier, at the end of the sentence: "Wir fahren am Montag nicht."

Sie redet nicht. She isn't talking. Wir sehen ihn nicht. We don't see him. Sie schenkt ihm das Buch nicht. She's not giving him the book. Wir gehen heute Nachmittag nicht. We're not going this afternoon. Wir arbeiten sonntags nicht. We don't work Sundays. Er spielt meistens nicht. He mostly doesn't play. Warum können wir ihn nicht sehen? Why can't we see him? If the sentence has a verb complement ("verbal idea"), however, that will be the part that is negated:

Er spielt nicht Schach. Er doesn't play chess. Mein Großvater fährt nicht Auto. My grandfather doesn't drive. Consider this last example: "Mein Großvater fährt nicht Auto." As a similar, previous example pointed out in I.c. ("Verb Complements Made from Other Parts of Speech"), the concept here is "Auto fahren". "Auto," in other words, is the verb complement, necessary to the predicate's meaning, and so it goes to the end of the sentence, with the "nicht" preceding it.

Were the auto conceptually the object of "driving", i.e. an augmentation, rather than a necessary part of the predicate, then the sentence would read: "Mein Großvater fährt dieses Auto nicht."Another point: If the element following the nicht moves to the first position, inverting the word order, the nicht does not move with it:

Hier arbeitet sie nicht. She doesn't work here. Bei mir darfst du das nicht sagen. At my house you can't say that. Nach dem Essen gehen wir nicht spazieren. We're not taking a walk after dinner. Nach Hause gehen wir nicht. We're not going home. These rules describe the most usual situations, but it is possible to create special emphases when placing nicht immediately in front of the element to be negated. If this placement differs from the above examples, then a "sondern" (but rather) is probably called for:

Du sollst nicht ihm das Geld geben, sondern mir. You should give the money not to him, but to me. Sie schenkt ihm nicht dieses Buch, sondern ein anderes. She's not giving him this book, but a different one. Wir gehen nicht heute ins Theater, sondern morgen. We're not going to the theater today, but tomorrow. When an adverb is negated as a sentence fragment, it can be thought of as occupying the first position, so that the nicht follows it:

hier nicht not here heute nicht not today am Sonntag nicht not on Sunday

VI. "Non-Elements:

Main clauses can begin with so-called "non-elements", which do not affect the subsequent word order. They can be thought of as occupying "position 0". They fall into three categories:

a. Coordinating conjunctions, which introduce an independent clause. The most common are aber, denn, oder, sondern, and und:

Sie war auch im Kino, aber ich habe sie nicht gesehen. She was also at the movies, but I didn't see her.

Er wollte nicht kommen, denn2 heute Nacht hat er schlecht geschlafen.He didn't want to come, because he slept badly last night.

Wir können es mitnehmen, oder wir können es hier essen.We can take it along, or we can eat it here.

Du kannst mir das Geld gleich geben, oder du kannst später bezahlen.You can give me the money right away, or you can pay later.

Er wohnt nicht mehr in der Stadt, sondern er ist aufs Land gezogen.He doesn't live in the city any more, but rather he's moved to the country.

Du hast das bestellt, und jetzt musst du es essen.You ordered that, and now you have to eat it.

They don't bite; they just want to play!

[Ad for the Berlin ice hockey team,

Die Eisbären (= Polar Bears)]A comma can also serve as a kind of "coordinating conjunction." Run-on sentences (two main clauses joined only by a comma) are illegal in English and are most quickly fixed by a semi-colon, but they are fine in German (which tends to use semi-colons very sparingly):

Wir sind nicht schwimmen gegangen, es war zu kalt. We didn't go swimming; it was too cold. b. Interjected words or phrases that are set off by commas. The most common are ja and nein:

Ja, ich habe diesen Witz schon gehört. Yes, I've heard that joke already. Nein, du hast schon genug gegessen. No, you've already eaten enough. In addition to ja and nein, these interjected words or phrases can be exclamations or transitions that introduce the main clause that follows. They are always set off by a comma:

Ach, das Leben ist so schwer! Oh, life is so hard! Übrigens, ich habe den Flaschenöffner vergessen. By the way, I forgot the bottle-opener. Nun, wir können immer auch zu Fuß gehen.3 Well, we can always go on foot, too. c. Another possible "non-element" is a preceding independent clause, which is always set off by a comma:

Er sagte, er wollte uns helfen. He said he wanted to help us. Ich weiß, du hast nichts Böses gemeint. I know you didn't mean anything bad. Ich habe schon gesagt, du kannst mit uns fahren. I already said, you can ride with us. Note that, in contrast to the "run-on sentences" discussed above in part "a" ("Coordinating conjunctions"), these examples are "independent" only in a grammatical sense. "Er sagte," "Ich weiß," etc. do not form a clause that can logically stand alone, but in terms of word order, they behave like a main clause.

When a dependent clause does fill the first position, whatever its function otherwise, it requires inverted word order to follow:

Weil wir morgen arbeiten müssen, sollten wir jetzt nach Hause gehen. Since we have to work tomorrow, we ought to go home now.

Bevor wir anfangen, sollten wir uns vorstellen.Before we begin we ought to introduce ourselves.

Was sie damit meinte, weiß ich nicht.What she meant by that I don't know.

In a city that never sleeps [i.e., Berlin], no one can afford tired feet. - "Es" can also be part of an expression in which it is the subject of "an impersonal verb." Here, too, it acts like a standard pronoun subject:

In the "inverted word order" some element other than the subject (or the finite verb) occupies the first position. While this first element receives a bit more emphasis, the effect is not especially strong. Contrast this with Yiddishisms in English like, "On the floor you throw the salad?!" "A shot in the head he needs."

With age, chronic iron, nickel, and copper deficiencies often appear. Some examples of inverted word order. Note that the elements placed in the first position tend to provide new information:

Colloquial speech sometimes makes use of word-order expectations to achieve a particular effect. By leaving the first position empty but putting the subject after the finite verb, the speaker can actually emphasize the object that should have been been there. Note that the English equivalent is more likely to omit the subject:

DasMuss sie ja nicht.SheDoesn't have to.DasHabe ich schon getan.IDid that already.DasWissen wir schon.WeAlready know that.DasGlaube ich nicht.IDon't believe it.Alfred? DenKenne ich nicht. Alfred?IDon't know him.

The pronoun "es", when used as a subject, has some particular functions that deserve special attention, some of which have implications for word order:

Again: this section first establishes the basic structure of declarative main clauses in German. After that it will provide links to treatments of the variations that are provided by questions, commands, and three categories of dependent clauses: subordinate, relative, and infinitive.

The examples that are treated in this section are in the active voice and indicative mood. By and large, sentences in the passive voice or the subjunctive mood adhere to the same basic rules of word order.

I. The Predicate (= Verb Phrase):

The most important concept for determining word order is the predicate, sometimes called the "verb phrase" or "the verbal idea". In its most basic form, it consists only of a single, finite verb. The finite verb is the one that gets conjugated to agree with the subject, as well as to reflect voice, mood, and tense:

I.a. The Position of the Finite Verb:

In a German declarative sentence, the finite verb always stands in the second position,

while other elements can be moved around to indicate emphases in meaning:

In the first example ("Der Mann beißt den Hund"), the nominative subject ("der Mann") is in the first position. In the second example ("Den Hund beißt der Mann"), the accusative object ("den Hund") occupies the first position, and the subject is third. In both instances, the finite verb is situated in the second position.

This rule about placement is so firm that someone who has been asked a question can casually reply, "Weiß nicht", and it is clear that the subject ("ich") has been omitted (compare the English: "Don't know"). Similarly, when hearing "Weiß ich nicht" or "Tut er nicht," everyone knows that the initial word, the object "das," has been omitted and that the finite verb is actually in the second position.

|

|

|

| Towards this moment we have been working for 12 years. Many patients with Parkinson's disease can now live more normally again. | |

But the predicate can also have more complex structures, comprising more than just the finite verb. When the predicate consists of more than one element (i.e., a finite verb plus a "verb complement"), the finite verb remains in the second position, while the other parts go to the end of the clause. German grammarians call this bifurcated structure "die Satzklammer" (= the sentence bracket).

Footnotes:

1

Sometimes this structure houses the highly colloquial use of "tun" with an infinitive:

"Arbeiten tut er nicht" [Work (is something) he doesn't do]. "Tun" plus an infinitive

is generally found only in dialects and in the speech of small children ("Sie tut es wegwerfen" [She throws it out]),

but some set phrases are common: "Sie tun nichts als klagen" [They do nothing but complain].

Note the historical link to the English use of "do" plus the infinitive, both in emphatic statements and questions

("I do like that"; "Do you think that's necessary?").

back to text

2

Note that "denn," in contrast to "weil," does not cause the finite verb to go to the end.

back to text

3

Note the distinction between this sentence and "Nun können wir zu Fuß gehen"

[Now we can go on foot], in which the adverb nun occupies the first position and thus inverts the

word order.

back to text